Position paper di AIFIRM[1]

Abstract

A causa dell’attuale recessione, in fase di validazione dei sistemi di rating, molte Banche si trovano ad affrontare problemi di sottostima dei tassi di default osservati per alcuni segmenti di clientela, che si concretizzano in frequenti failures dei test di calibrazione “classici”, quali i test binomiali.

Le ragioni che possono portare a tali risultati, anche per un sistema di rating performante, sono molteplici, ma le più critiche sono la filosofia del sistema di rating in validazione e la correlazione tra default.

Per una migliore comprensione delle filosofie sottostanti, ovvero dei sistemi di rating point in time (PIT) o through the cycle (TTC), è necessario distinguere due concetti di “ciclicità”: uno si riferisce al processo di ordinamento delle controparti e quindi al processo di assegnazione dello score, in termini di tassi di migrazione tra classi di rating e loro stabilità, l’altro al processo di calibrazione ovvero alla fase di assegnazione delle PD. Il grado complessivo finale di ciclicità di un sistema di rating dipende da entrambi i processi.

In generale, i rating PIT sono associati a PD che riflettono le caratteristiche correnti della controparte, osservate con riferimento alle condizioni correnti del settore in cui opera e/o dell’economia nel suo complesso. Durante una fase di recessione, i rating PIT migrano verso classi di rating peggiori, pertanto nelle valutazioni PIT l’aumento della rischiosità del portafoglio si riflette in una migrazione di controparti dalle classi di rating migliori alle classi peggiori; di conseguenza, nel corso del tempo i tassi di default per una determinata classe di rating sono meno volatili mentre le matrici di migrazione sono più instabili. Al contrario, le valutazioni TTC sono (più) stabili nel tempo, non comportano una “reazione istantanea” di tali rating e quindi i tassi di default per una data classe di rating sono più volatili e le matrici di migrazione meno disperse. I modelli di rating comunemente utilizzati non corrispondono mai perfettamente alle tipologie “stilizzate” ed estreme sopra definite, ma si collocano in situazioni ibride.

I livelli di ciclicità del processo di attribuzione del rating e del processo di calibrazione condizionano dunque l’idoneità e l’accessibilità dei test di calibrazione, come quelli indicati dal Working Paper n.14 (Comitato di Basilea, 2005), di norma sotto l’ipotesi di indipendenza dei default. Infatti, essi sono concepiti per modelli tendenzialmente PIT e risultano quindi estremamente “penalizzanti” per modelli più vicini a una filosofia TTC. I problemi di idoneità si pongono in termini di coerenza “teorica” tra tipologia di test di calibrazione adottati e filosofia del sistema di rating; i problemi di accessibilità si pongono in termini di probabilità di superare i test da parte di modelli di rating con livelli di ciclicità differenti.

Dunque, è possibile assumere diverse prospettive: come definire il processo di assegnazione del rating per superare i test di calibrazione? Come definire il processo di quantificazione delle PD per superare i test di calibrazione? Come sviluppare test di calibrazione che tengano in considerazione il livello di ciclicità del sistema di rating?

Teoricamente e in funzione delle scelte metodologiche effettuate, sia in termini di ordinamento delle controparti sia di calibrazione delle PD, è possibile costruire una matrice teorica di riferimento della filosofia di rating sottostante (PIT, TTC, sistemi ibridi).

Dall’analisi della normativa di Vigilanza di riferimento (Comitato di Basilea, CRR, Consultation Paper dell’EBA) è possibile ritrovare molti passaggi che trattano il tema della ciclicità, ma non sembra emergere un orientamento prevalente PIT/TTC in termini di assegnazione del rating, mentre sembra prevalere un indirizzo più spiccato per calibrazioni TTC che garantiscono una maggiore stabilità del requisito patrimoniale (indirizzo che purtroppo non trova sempre riscontro nelle verifiche ispettive di validazione, dove si chiede spesso ai modelli di rating di riflettere le condizioni economiche più recenti).

Anche la letteratura dedica molti paper al tema della calibrazione. Dopo aver esaminato questi contributi, nel corso del 2015, il gruppo di lavoro AIFIRM ha predisposto una survey per valutare le principali caratteristiche dei sistemi di rating correntemente usati dalle banche italiane, nonché le diverse applicazioni gestionali e le più opportune filosofie di rating adottate e i futuri sviluppi. Le banche aderenti sono state: Banca Popolare di Bari, Banca Popolare di Vicenza, Banco Popolare, BMW Bank, BPER, Cariparma, Che Banca!, Compass, Credem, Intesa Sanpaolo, Unicredit. Mentre per il Retail si è osservata una convergenza di opinioni sulla filosofia di rating attesa per i prossimi anni (maggiormente orientata al PIT), per i segmenti SME e Corporate le banche hanno una differente visione sul futuro orientamento dei sistemi di rating. Il legame controverso tra filosofia del sistema di rating e applicazioni gestionali, che si ritrova nelle risposte alla survey, è indicativo di un quadro concettuale e normativo incerto.

Il Position paper AIFIRM propone in conclusione 4 possibili direzioni da intraprendere per evitare che la simultanea coerenza con i requisiti normativi in materia di costruzione di modelli, in materia di calibrazione, i test suggeriti dal WP 14, le applicazioni gestionali e i requisiti di use test portino ad un insieme vuoto.

Direzione 1: il Regolatore definisca la misura del grado di ciclicità dei sistemi di rating e richieda dei test di calibrazione corretti per il ciclo. Le Banche sviluppano quindi modelli di rating con il grado di ciclicità desiderato, nel rispetto dei requisiti regolamentari e di business, ed eseguono la convalida annuale utilizzando il framework di calibrazione corretto per il ciclo. Purtroppo, al momento il quadro metodologico non è ancora completamente consolidato e le soluzioni metodologiche individuate sembrano essere data-intensive rispetto alla lunghezza delle serie storiche a disposizione delle Banche.

Direzione 2: Il settore bancario di concerto con i Regolatori sviluppa un approccio ai test di convalida su più dimensioni: l’idea potrebbe essere quella di sviluppare una serie di test che valutino le prestazioni dei modelli e la loro conformità con i diversi (e spesso conflittuali) requisiti normativi. I nuovi test da introdurre, che si basano su diverse ipotesi di correlazione, ciclicità, etc… e che al momento purtroppo giocano un ruolo marginale nella discussione con i Regolatori, a causa anche della mancanza di una prassi condivisa e consolidata del settore bancario, potrebbero produrre come risultato una valutazione simultanea delle diverse dimensioni in un approccio a semaforo con soglie quantitative e giudizi qualitativi.

Direzione 3: il Regolatore definisca il target in termini di test di calibrazione e lasci che le Banche scelgano come allineare i processi di assegnazione e di calibrazione. Questa soluzione, pur avendo il vantaggio della chiarezza dei risultati, imporrebbe importanti vincoli sulle scelte metodologiche delle Banche, con il rischio di soluzioni non soddisfacenti per il business, a meno che non si rilassi il vincolo di use test e si conceda di utilizzare sistemi di rating diversi in funzione delle applicazioni gestionali.

Direzione 4: il Regolatore definisca interamente i requisiti in termini di processo di assegnazione del rating, processo di calibrazione delle PD, i test di calibrazione, lo use test. Tale approccio, che pare essere il più completo, risulta anche essere il più oneroso e complesso da definire.

The problem

Often internal rating systems do not fully satisfy standard calibration tests used for PD validation.

According to the document “Studies on validation of internal rating systems” issued by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (WP n. 14, May 2005), still a milestone on this topic, “correct calibration of a rating system means that the PD estimates are accurate. Hence, for examining calibration somehow the differences of forecast PDs and realised default rates must be considered. This can be done simultaneously for all rating grades in a joint test or separately for each rating grade, depending on whether an overall assessment or an in detail examination is intended”.[2]

Many reasons could lead to fail calibration tests even by otherwise well performing rating systems. Two reasons are particularly critical: rating philosophy (TTC versus PIT ratings) and default correlation.

“The results of this analysis suggest that the pooled default probability assigned to each rating grade and its dynamics strongly depend on the type of rating system and the PD estimation method. The estimation from historical default rates is most meaningful when the pooled PDs are unstressed, which means that they are unbiased estimates of the likelihood of default in the following year. Furthermore, the analysis suggests that the long-run average default frequency for a through-the-cycle bucket will not provide a good approximation of that bucket’s unstressed pooled PD. The reason is that the unstressed pooled PD will tend to be lower than the long-run average default frequency during cyclical peaks and higher than the long-run average default frequency during cyclical troughs”.[3]

“Due to correlation between defaults in a portfolio, observed default rates can systematically exceed the critical PD values if these are determined under the assumption of independence of the default events. This can happen easily for otherwise well-calibrated rating systems. As a consequence, on the one hand, all tests based on the independence assumption are rather conservative, with even well-behaved rating systems performing poorly in these tests. On the other hand, tests that take into account correlation between defaults will only allow the detection of relatively obvious cases of rating system miscalibration”.[4]

The WP 14 arrives at rather undetermined conclusions: “Therefore, statistical tests alone will be insufficient to adequately validate an internal rating system. Nevertheless, banks should be expected to use various quantitative validation techniques, as they are still valuable tools for detecting weaknesses in rating systems.”[5] “In conclusion, at present no really powerful tests of adequate calibration are currently available. Due to the correlation effects that have to be respected there even seems to be no way to develop such tests. Existing tests are rather conservative – such as the binomial test and the chi-square test – or will only detect the most obvious cases of miscalibration as in the case of the normal test. As long as validation of default probabilities per rating category is required, the traffic lights testing procedure appears to be a promising tool because it can be applied in nearly every situation that might occur in practice. …Nevertheless, it should be emphasised that there is no methodology to fit all situations.”[6]

The WP 14 has assessed the quality of PD estimates by using methodologies based on the Binomial test, Chi-square test, Normal test, Traffic lights approach. These are still considered the “standard” reference framework for validating rating models’ calibration.

A large number of scholars’ and practitioners’ papers are devoted to the issue of ratings calibration. After having examined these contributions, the AIFIRM work group on calibration has also prepared a questionnaire submitted to participant banks in order to assess current practices and future developments in the industry. The conclusions of the overall analyses and discussions have led to the proposal included in this position paper.

Key question

Supervisors and the industry are searching for new frameworks for validating rating models’ calibration. The key question is: can calibration tests be discussed per se? The findings of WP 14 in year 2005 already suggested that the answer is no.

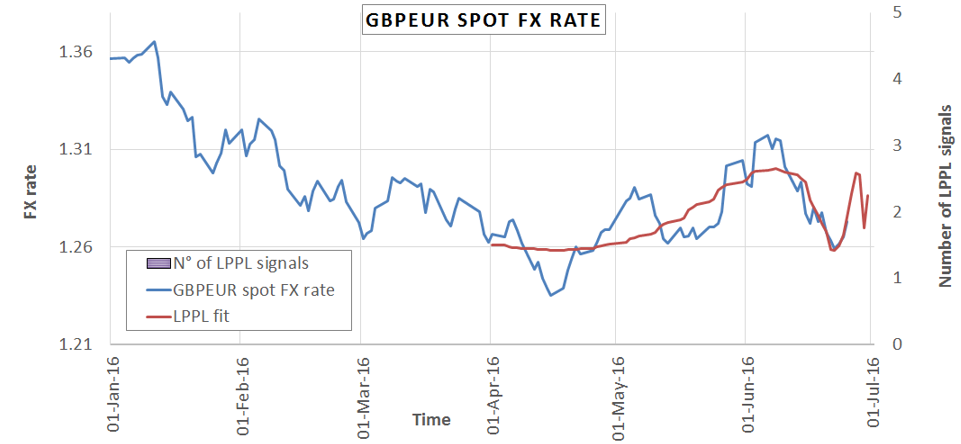

In fact, the impacts of rating philosophy and default correlations are many (Figure 1) and they also appear to be interconnected[7].

Figure 1 Rating philosophy impacts.

The role of the degree of pitness

On one hand, the possibility that rating systems and estimated PD comply with standard calibration tests strongly depends on their degree of pitness.[8] On the other hand, we still lack an universal definition of the degree of pitness of a rating system[9].

In general, it is assumed that PIT ratings and/or associated PDs are focused on the current conditions of the borrower, observed in the current conditions of the business sector and/or of the economy as a whole. During a recession, PIT ratings migrate towards worse rating classes; therefore, in PIT ratings, the increase in the portfolio riskiness is reflected in a rating drift towards worse rating classes; hence, default rates for a given rating class are less volatile over time, that is in good and bad times. On the contrary, TTC ratings are (more) stable over time, and therefore default rates for a given rating class are more volatile (because in good and bad times the different portfolio default rates are factored in default rates volatility per rating class and not in ratings migrations).

However, a better understanding of the PIT/TTC ratings requires to distinguish two technically different concepts of degree of pitness: one is referred to ratings assignment processes, the other is referred to PDs calibration processes. The final overall degree of pitness of “the system” depends on both.

Many rating model building choices affect the “ratings degree of pitness” (in terms of migration rates, rating reversal rates,…), among which are the following:

- Datasets time span (single-period, multi-period)

- Observation period (the target time of prediction: 3m, 1y, 2y, 3y, 5y)

- Nature of independent variables (behavioral versus strategic)

- Structure of independent variables (last data, averaged data)

- Perimeter of default definition (from past dues to filing bankruptcy petition)

- Model estimation techniques and expert-judgment role.

Many calibration choices affect the “PDs degree of pitness” (in terms of closeness to actual DRs), among which are the following ways to associate PDs to ratings:

- Downturn PDs

- Last year DRs

- Recent years DRs

- Predicted PD central tendency

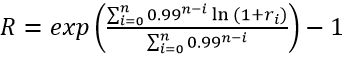

The degrees of pitness of rating assignment processes and rating quantification processes strongly impact on the suitability and accessibility of calibration tests (Figure 2) such as those indicated by the WP n.14 (the Binomial test, the Chi square test, the Normal test and the Traffic light approach). Suitability concerns the theoretical coherence of the test with the rating model philosophy. Accessibility concerns the probability to pass the test by rating models having different degrees of pitness.

Figure 2 Degree of pitness and suitability/accessibility of calibration tests.

Therefore the following questions arise:

- Have we to adjust rating assignment processes in order to meet calibration tests requirements?

- Have we to adjust rating calibration processes in order to meet calibration tests requirements (whereas rating assignment processes are considered exogenous)?

- Have we to adjust rating assignment processes and rating calibration processes in order to meet calibration tests requirements?

- Have we to adjust calibration tests in order to take into account the degree of pitness of the rating system (that is considering rating assignment and calibration processes as exogenous)?

Theoretically we can have different possible combinations of choices related to rating assignment and calibration. Let’s consider the four extreme cases (the four corners of Figure 3). Some choices, in either rating assignment or rating quantification processes cannot lead to pass current standard calibration tests.

The problem is twofold:

a) in order to pass calibration tests, specific choices on rating assignment and calibration are required,

b) some of the possible combinations are restricted by the regulation.

Figure 3 Combinations of the degree of pitness of rating assignment and rating quantification processes.

First of all, many paragraphs of Basel 2 regulation[10] are influencing the PIT or TCC orientation of rating assignment and/or calibration processes (we use PIT/TTC combined with assignment/calibration after the symbol ► to give our view of the orientation implied in the rule):

a) 414. “Although the time horizon used in PD estimation is one year (as described in paragraph 447), banks are expected to use a longer time horizon in assigning ratings” ► TTC assignment

b) 415. “A borrower rating must represent the bank’s assessment of the borrower’s ability and willingness to contractually perform despite adverse economic conditions or the occurrence of unexpected events. For example, a bank may base rating assignments on specific, appropriate stress scenarios.” ► TTC assignment

c) 444. “Internal ratings and default and loss estimates must play an essential role in the credit approval, risk management, internal capital allocations, and corporate governance functions of banks using the IRB approach” ► Undetermined, given that different applications may be better suited by systems with different degree of pitness

d) 447. “PD estimates must be a long-run average of one-year default rates for borrowers in the grade” ► TTC calibration

e) 452. “A default is considered to have occurred with regard to a particular obligor when either or both of the two following events have taken place…. • The obligor is past due more than 90 days on any material credit obligation to the banking group” ► PIT assignment and calibration

f) 461. “Banks must use information and techniques that take appropriate account of the long-run experience when estimating the average PD for each rating grade” ► TTC calibration

g) 463. “Irrespective of whether a bank is using external, internal, or pooled data sources, or a combination of the three, for its PD estimation, the length of the underlying historical observation period used must be at least five years for at least one source. If the available observation period spans a longer period for any source, and this data are relevant and material, this longer period must be used.” ► TTC calibration

Let’s consider now the CRR (Capital Requirement Regulation, EU 2013), art. 180, Requirements specific to PD estimation: “institutions shall estimate PDs by obligor grade from long run averages of one-year default rates” ► TTC calibration.

Eventually, let’s consider the Draft Regulatory Technical Standards On the specification of the assessment methodology for competent authorities regarding compliance of an institution with the requirements to use the IRB Approach in accordance with Articles 144(2), 173(3) and 180(3)(b) of Regulation (EU) No 575/2013, EBA Consultation Paper of 12 November 2014. At page 77 in the box with “text for consultation purposes”: “the PD estimates should reflect the long run average of one-year default rates in order to ensure that they are relatively stable over time and extensive cyclicality of own funds requirements is avoided. It means that the PD estimates should be based on a period representative of the likely range of variability of default rates in that type of exposures in a complete economic cycle” . ► TTC calibration.

In summary, the regulation tends to push towards a TTC orientation for rating quantification (calibration), whereas more contradictory requirements are set for rating assignment processes. Reconsidering now Figure 3, we can conclude that none of the 4 extreme cases is at the same time:

- Compliant with regulatory requirements in terms of TTC rating assignment processes

- Compliant with regulatory requirements in terms of rating calibration processes based on a TTC approach

- Capable to pass calibration tests typically used in validation processes

In addition, a fourth perspective has not yet taken into consideration: the usefulness of “the system” for bank management processes. In fact, given the “use test” rule, the same rating system should be used for both regulatory and management purposes.

In conclusion, what we currently observe is:

a) an explicit TTC orientation of regulation for rating quantification processes,

b) a mixed PIT/TTC kinds of requirements in the regulation as far as rating assignment processes are concerned, and an (up to now) softer application by supervisors of TTC-oriented assignment processes regulatory requirements (this seems to be the case of supervisory validation processes for IRB banks).

As a consequence, the current situation is as in Figure 4, where red indicates systems not allowed by the regulation, olive indicates systems we are not yet capable to build (because of pure TTC or pure PIT assignment processes), green indicates what regulation wants (but standard calibration test will fail), and blue indicates what banks have done (but standard calibration test often fail for the insufficient degree of pitness of rating assignment processes).

Figure 4 An helicopter view of the situation.

Degree of pitness of rating assignment processes of current models

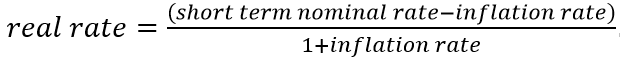

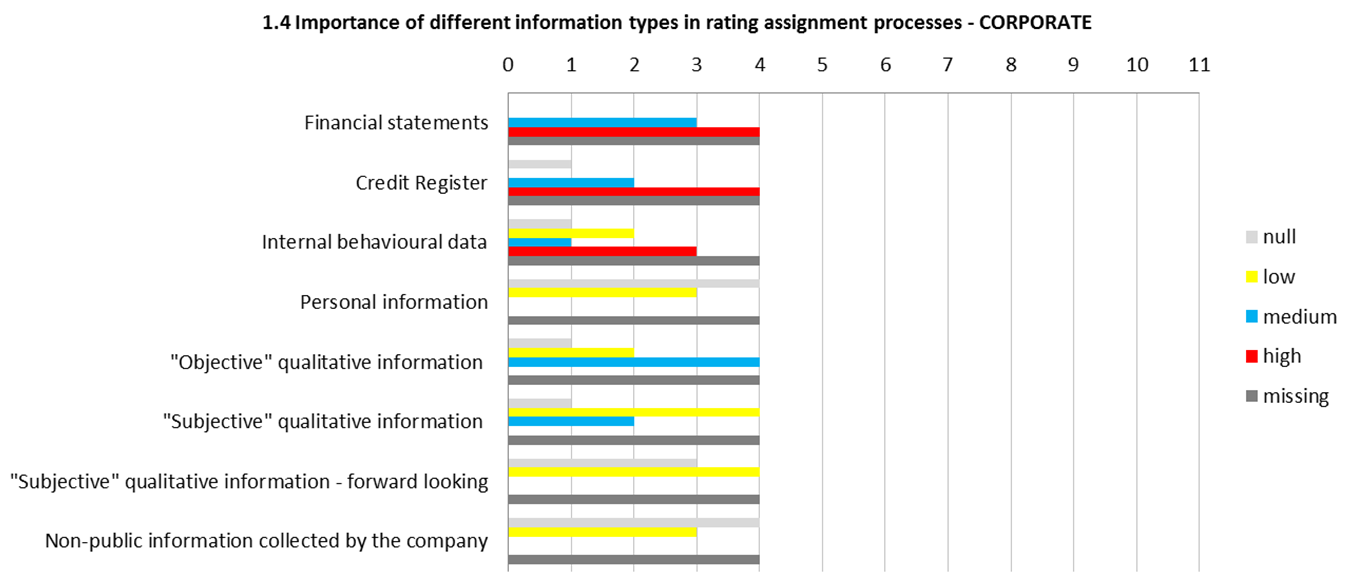

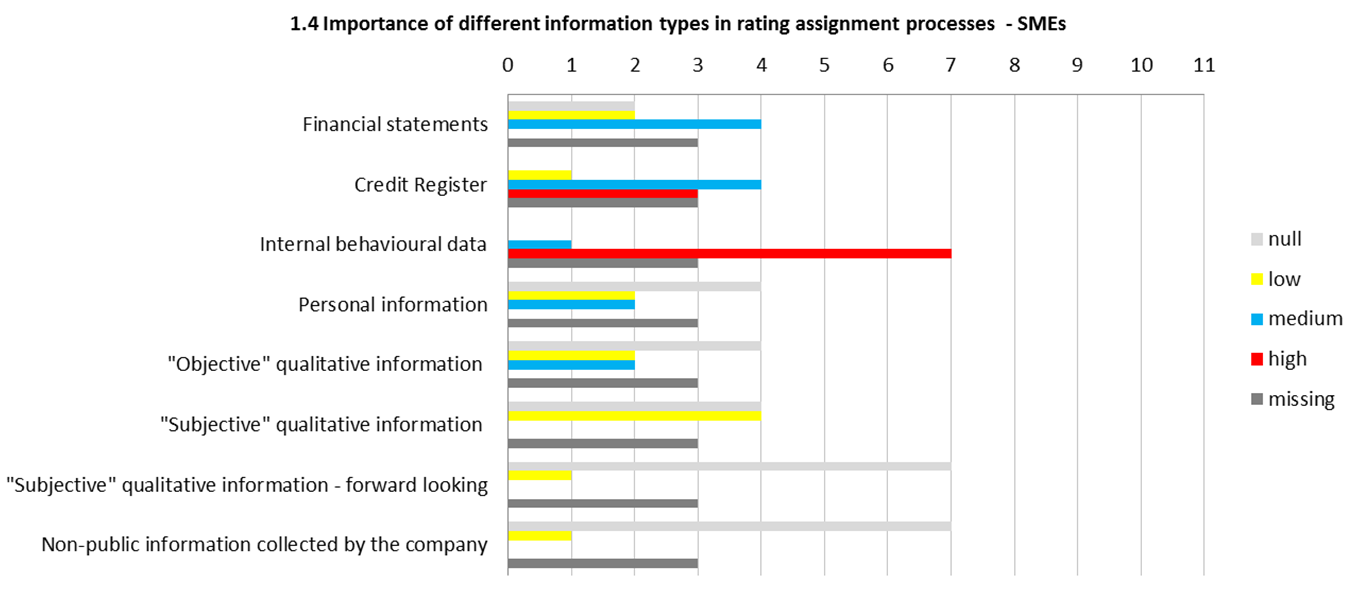

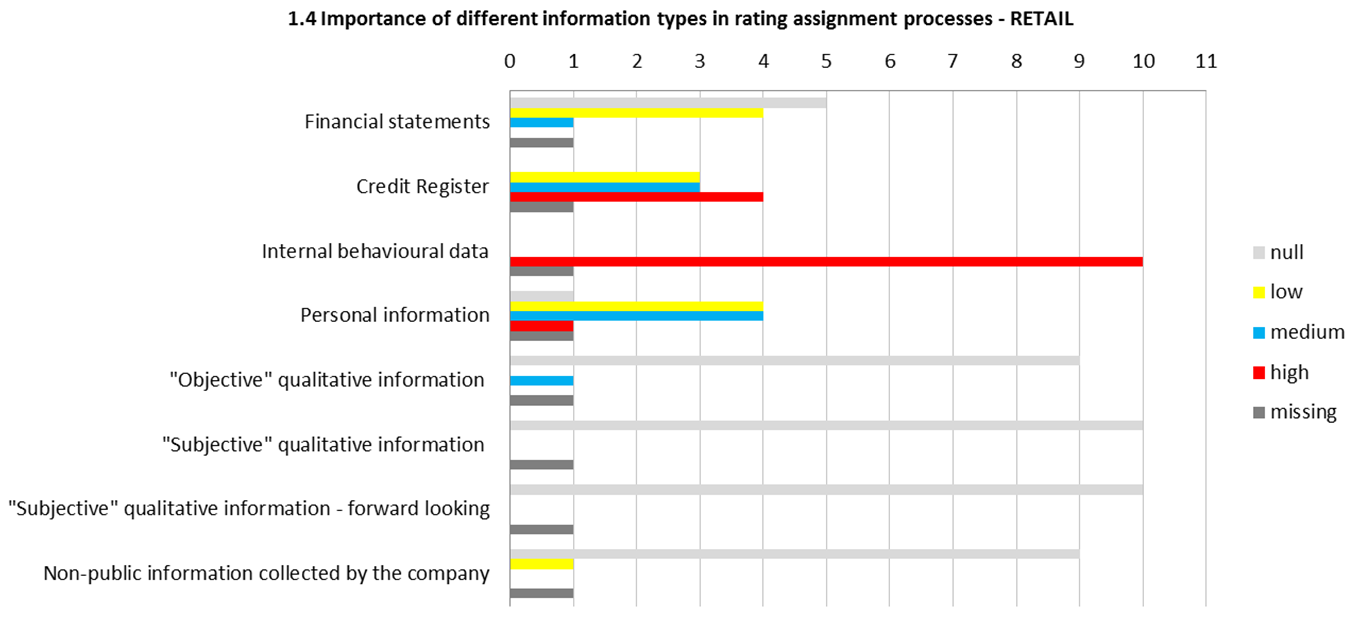

In order to assess some relevant characteristics of rating systems currently used by Italian banks, the AIFIRM group on Validation of models’ calibration has launched in 2015 a survey among its members. The following institutions has answered: Banca Popolare di Bari, Banca Popolare di Vicenza, Banco Popolare, Bmw Bank, Bper, Cariparma, Che Banca!, Compass, Credem, Intesa Sanpaolo, Unicredit.What is the importance of different Information types in the model? The answers for rating models for corporate segments have outlined that financial statements, internal behavioural data and credit register data have a relevant role, whereas other qualitative pieces of information, both objective and subjective only have a minor role. In the case of models for SMEs, internal behavioural data and credit register data have an even more relevant role. In the case of models for the retail segment, the role of internal behavioural data and credit register data are of the utmost importance. See Figure 5.

Figure 5 Importance of different information types in rating assignment processes.

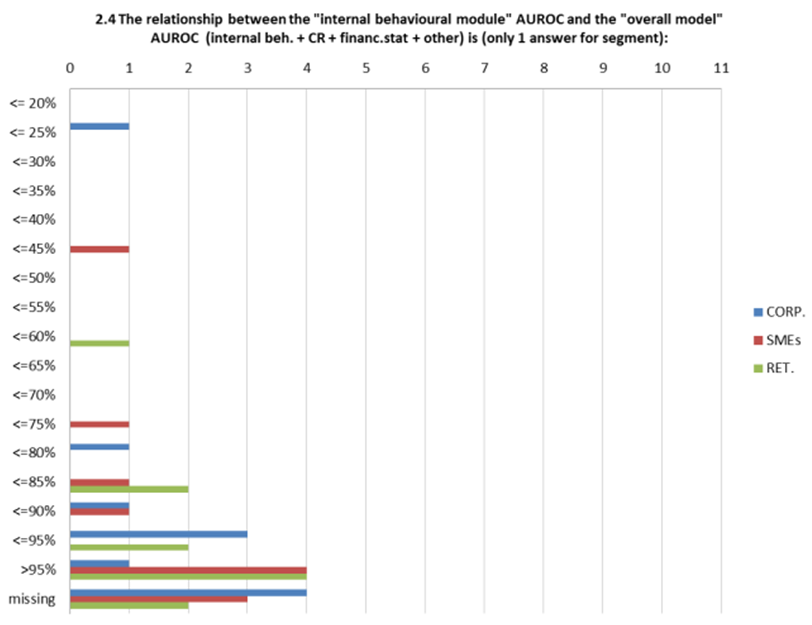

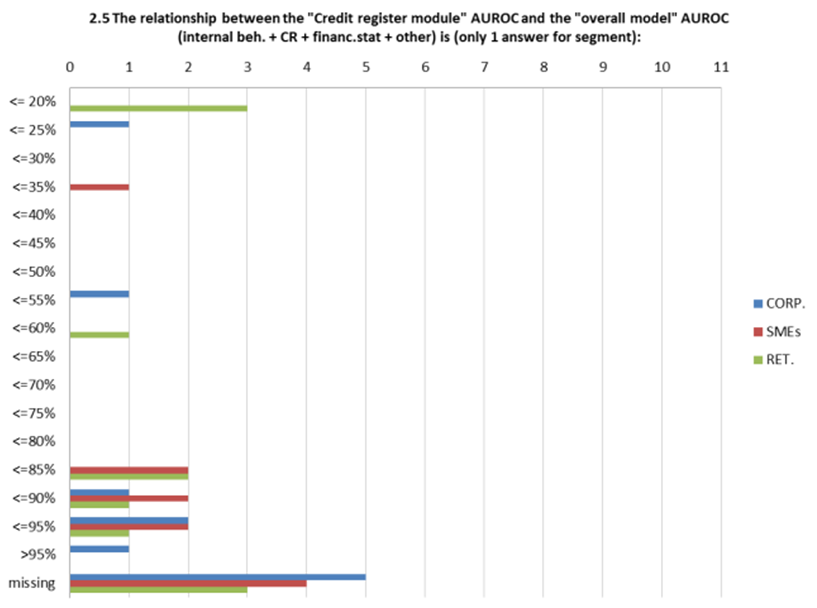

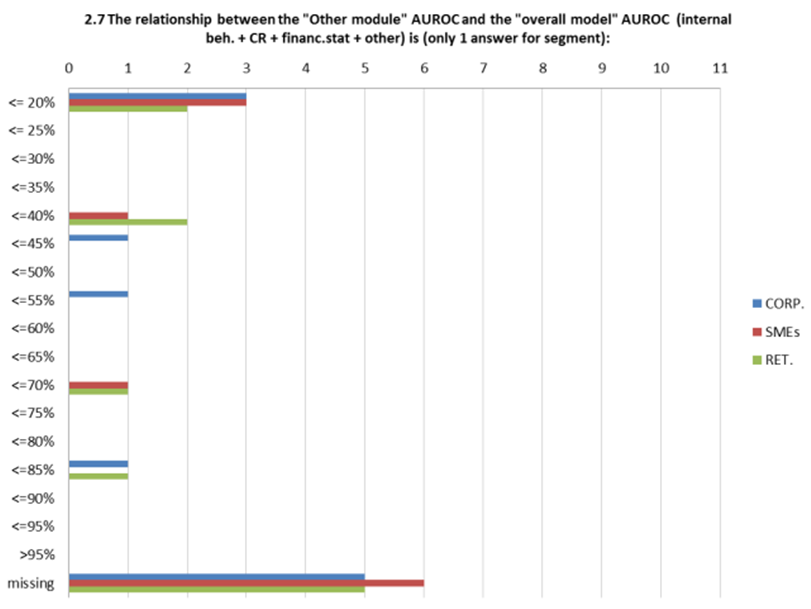

This qualitative perception of relative importance of different types of information is confirmed quantitatively by the ratio of the AuRoc of the individual module of the rating system (financial statement module, behavioral module, credit register module, “other information” module) and the final AuRoc of the system (Figure 6).

Figure 6 AuRoc ratios (individual module AuRoc divided by final model AuRoc.

In practice, in banks that have communicated these ratios, the modules based on behavioral or credit register data are driving the final AuRoc of the model with little contribution of other sources of information.

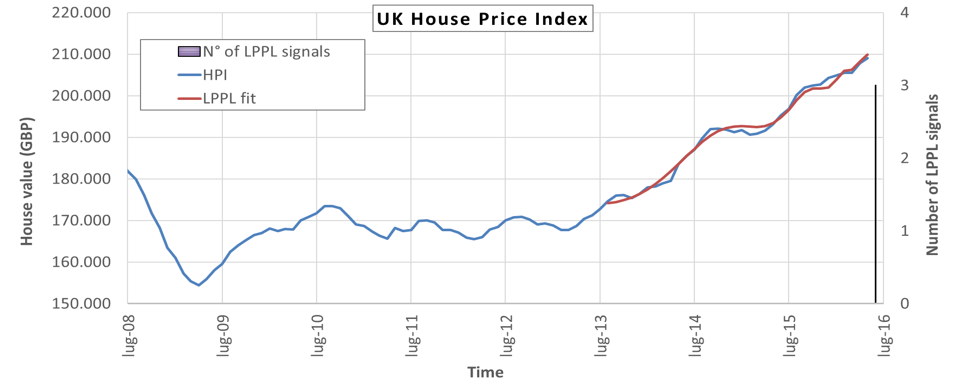

Behavioral or credit register data have two important features:

a) they lead to PIT ratings as the assignment process focus on data that are timely pieces of information but whose predictive power is short-sighted. In other words, they lead to strong but short-term predictions. When the high frequency updating of these data is also considered, the end result is very high migration rates of assigned ratings;

b) they contribute aggressively to the final model scores and ratings when the observation period in model estimation is one-year; as soon as the observation period is set to a longer time horizon[11], the estimation of the final model will attribute less relevance to this sort of data.

Rating models’ requirements for effective bank management

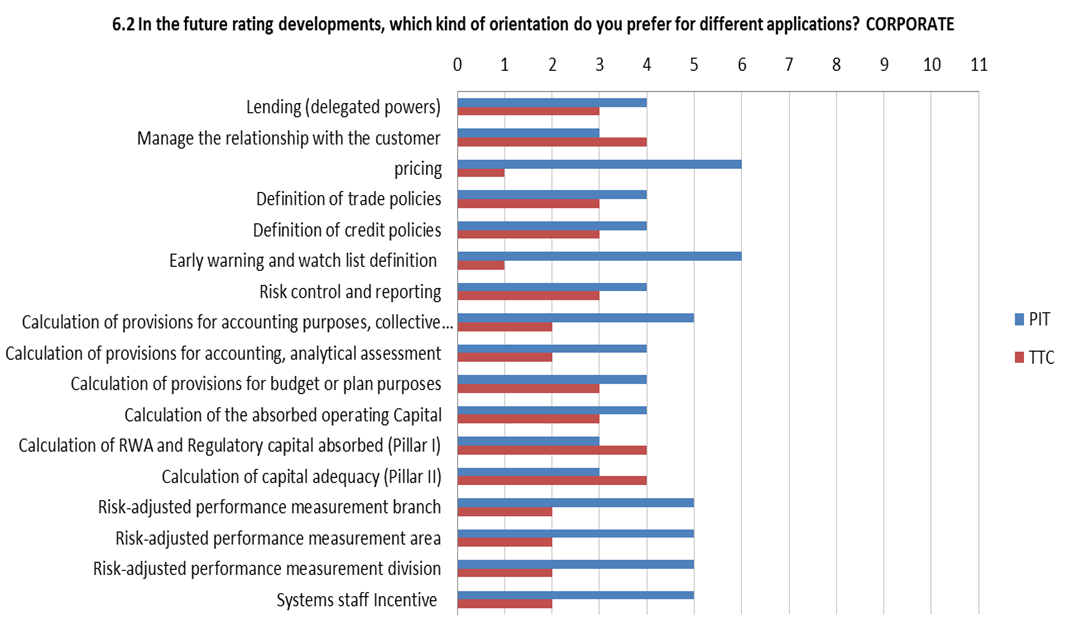

In bank management it is evident that different ratings philosophies are desired for different types of applications .

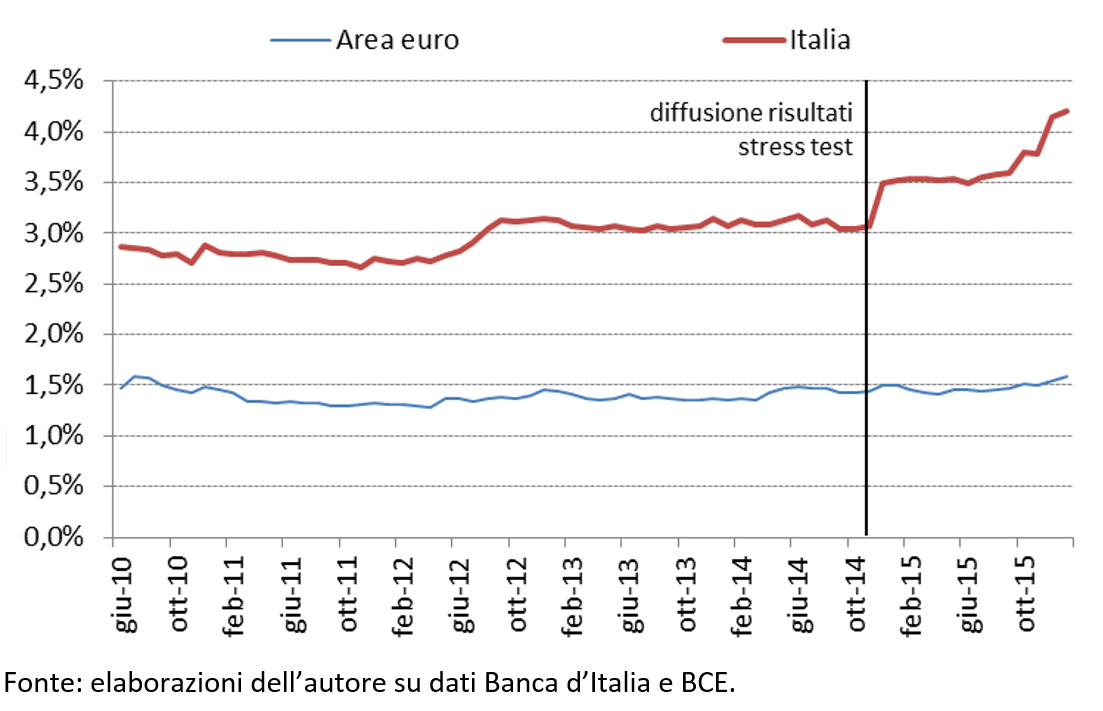

Figure 7 Desired degree of pitness of rating systems for different applications.

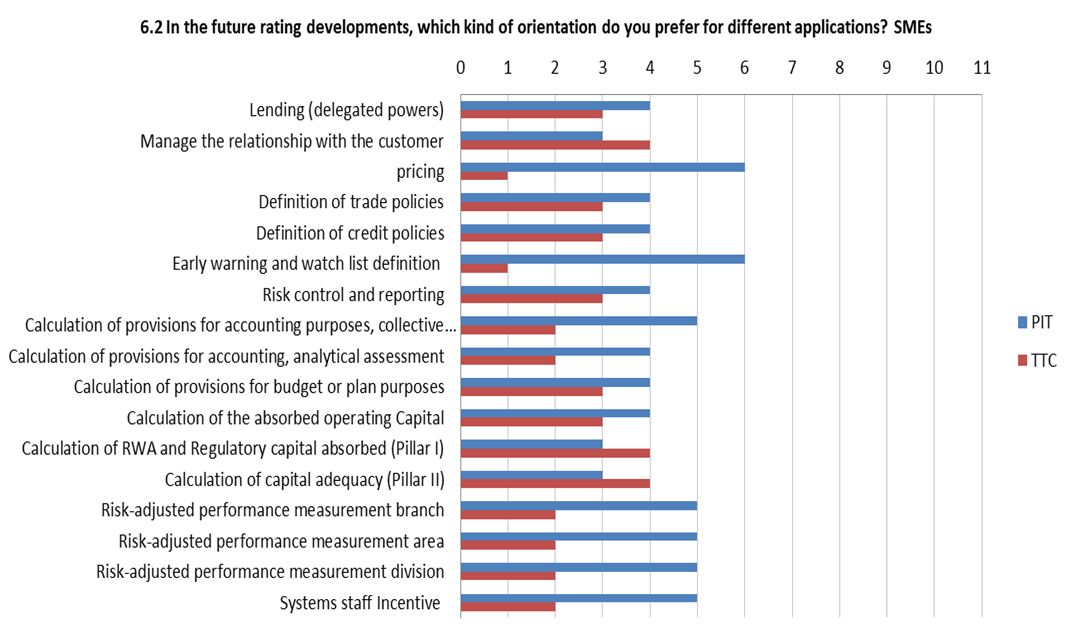

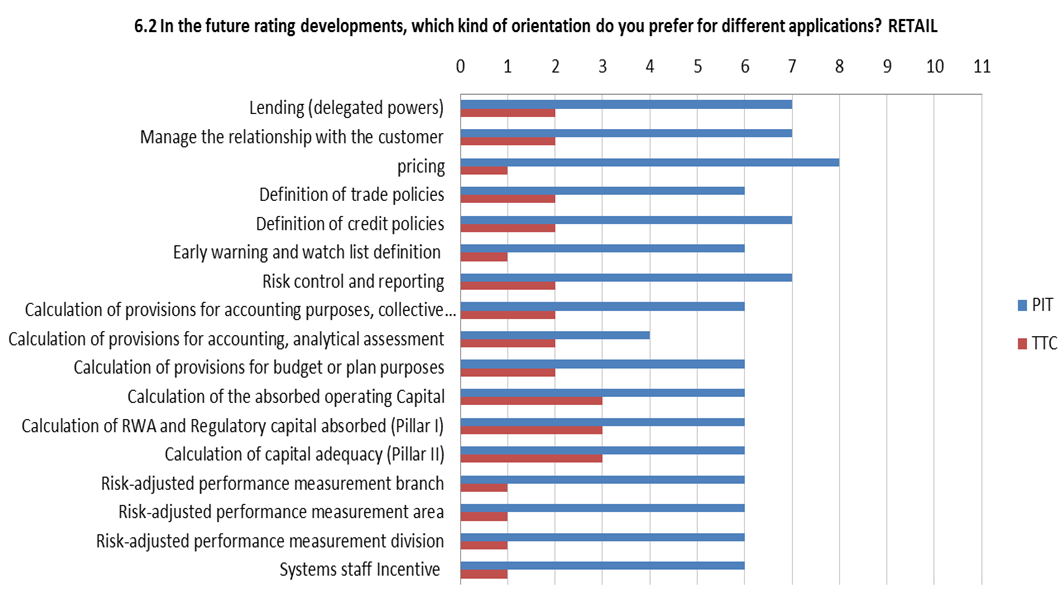

According to the already mentioned AIFIRM survey, of the five large institutions that answered in full to the question, two banks do not see the need to differentiate rating system PIT/TTC orientation according to the specific applications whereas three banks do differentiate, but with some divergence of opinion (Figure 8).

Figure 8 Desired PIT/TTC orientation of future model developments for different applications

In general, banks are looking forward to having an higher degree of pitness for the retail segment, whereas in the SMEs and corporate segments different banks have different views on the future orientation of rating systems (Figure 9).

The controversial link between the rating philosophy and rating applications in the answers by banks surveyed by AIFIRM is indicative of an uncertain conceptual and regulatory framework. Also the “use test” requirements is possibly a source of this unclear view. It is worth to remember that paragraph 444 of Basel 2 states initially that “Internal ratings and default and loss estimates must play an essential role in the credit approval, risk management, internal capital allocations, and corporate governance functions of banks using the IRB approach”, but immediately after it states that “It is recognised that banks will not necessarily be using exactly the same estimates for both IRB and all internal purposes. For example, pricing models are likely to use PDs and LGDs relevant to the life of the asset”.

Figure 9 Desired degree of pitness of future rating systems developments per applications and per segments

Conclusions

In conclusion, a simultaneous consideration of required compliancy with

a) regulatory requirements concerning model building (rating assignment processes)

b) regulatory requirements concerning model calibration (rating quantification processes)

c) standard calibration tests suggest by WP 14

d) the use test requirements leads to an empty set.

Therefore, there are four possible directions to undertake.

Direction 1. Measure the degree of pitness of ratings (assignment and calibration processes) in order to set adequate calibration tests that take account of the degree of pitness of the system. This requires a universally accepted measure of degree of pitness and the development of pitness-sensitive calibration tests in order to allow for the rating cyclicality. This implies that:

a) the Regulators define an agreed degree of pitness measure to apply to Banks’ rating models;

AND

b) the calibration test(s) is conveniently modified in order to factor in the rating models degree of cyclicality;

AND

c) Banks develop the models with the desired degree of pitness but in compliance with all the other requirements discussed above and perform the annual validation using the pitness-adjusted calibration framework.

This solution preserves the flexibility in model development for Banks, thus ensuring the consistence between business and regulatory purposes and reduce the weight of alleged methodological inconsistency in the regulatory framework.

Unfortunately, at the moment the methodological framework is not fully consolidated yet: there is not a common agreed degree of pitness measure and consistent tests set. Furthermore, available methodological solutions seem to be quite data intensive compared to the length of credit risk time series.

Direction 2. The industry agrees with Regulators a multidimensional approach to validation test. The idea is to develop a set of tests, each aiming at measuring the performance of the models and their compliance with different (even conflictual) regulatory requirements. Tests to be introduced are based on different hypotheses (correlations, degree of pitness measures, …). At the moment these tests only play a marginal role in the discussion with Regulators (NCA, ECB, EBA), probably because of absence of an industry best practice. The outcome would be a simultaneous assessment of the several dimensions in a traffic light approach involving both quantitative thresholds and qualitative judgments. The traffic light approach could be implemented with specific threshold for each test, differentiated for the degree of pitness of the model, the target segment (corporate, retail, HDP, LDP,…), number of rating classes of the system,…

Direction 3. Use a calibration test level as a target and let banks choose how to align assignment and calibration processes to the target calibration results. This direction to sort out the conundrum requires to adapt the development process in order to produce rating models able to comply with the calibration test(s) that has been defined by the Regulator. This implies that:

a) The Regulators clearly define the calibration test(s) that the rating model must comply with. Note that this would obviously have some consequences on the rating model properties, namely on its degree of pitness;

b) The Banks accordingly develop the models and perform the annual validation.

It can be argued that this solution, while having the pro of clarity, would impose serious constraints on the methodological choices. Banks may end up with models non satisfactory for their business purposes, unless the use test requirement is relaxed and the use of different rating systems for different purposes are allowed. Of course, the analysis of coherence of different rating systems becomes a part of the validation process.

Direction 4. Propose a new set up of regulation in order to get a better alignment of requirements in terms of rating assignment processes, PD calibration processes, calibration tests, use test. This solution leaves on regulators the entire burden of re-thinking assignment and calibration requirements, use test requirements and calibration tests framework setting. It could be the more comprehensive approach but also the most difficult and time expensive solution.

Sono disponibili sul sito www.aifirm.it l’Allegato 1 contenente l’analisi della letteratura realizzata da Valeria Stefanelli e l’Allegato 2 contenente il questionario di indagine realizzato anche con il prezioso contributo di Marco Salemi

References

- Aguais S. (2008), Designing and Implementing a Basel II Compliant PIT-TTC Ratings Framework, MPRA Paper No. 7004, posted 6. February 2008

- Alfonsi D. (2010), Informal Expert Working Group on Rating backtesting in a cyclical context Methodological Annex, Main findings and proposals, slides CEBS Consultative panel

- Altman E.I, and A. Rijken H. A. (2006), A Point-in-Time Perspective on Through-the-Cycie Ratings, Financial Analysts Journal, Vol. 62, n.1

- Blochlinger A., Leippold M. (2005), Testing probability calibration validation: application to credit scoring models, PAPER

- Boegelein L. (2005), Validation of Internal Rating and Scoring Models, Global Financial Services Risk Management, Ernst & Young

- Breinlinger L., Glogova E. and Hoger A. (2003), – Blochlinger A., Leippold M. (2005), Calibrations of rating system: A first analysis, PAPER

- Carlehed M. and Petrov A. (2012), A methodology for point-in-time–through-the-cycle probability of default decomposition in risk classification systems, Journal of Risk Model Validation, Vol. 6, n. 3, Fall 2012

- Castermans G., Martens D., Gestel T. V., Hamers B. and Baesens B. (2007), An Overview and Framework for PD Backtesting and Benchmarking, paper

- Cesaroni T. (2015), Prociclicality of credit rating systems: how to manage it, Working Papers, Banca d’Italia, September 2015

- Cornaglia A. (2010), Ciclicità dei rating e stress test 1. Filosofia e ciclicità nei sistemi di rating, presentazione, Finance Master Class Milano

- Cornaglia A. and Morone M. (2009), Rating philosophy and dynamic properties of internal rating systems: A general framework and an application to backtesting, MPRA Paper No. 14711, posted 19 April 2009

- EBA (2014), On the specification of the assessment methodology for competent authorities regarding compliance of an institution with the requirements to use the IRB Approach in accordance with Articles 144(2), 173(3) and 180(3)(b) of Regulation (EU) No 575/2013, EBA/CP/2014/36 (published November 12 2014)

- Engelmann B. and Rauhmeier R. (2006), Chapter 14: Statistical approaches to PD validation, in, The Basel II risk parameters: Estimation, Validation, Stress Testing with Applications to Loan Risk Management, Springer, II Edition:

- Fei F., Fuertes A. and Kalotychou E. (2011), Credit Rating Migration Risk and Business Cycles, Journal of Business Finance and Accounting (forthcoming).

- Gobeljic P. (2012), Classification of Probability of Default and Rating Philosophies, paper

- Kauko K. (2010), The feasibility of through-the-cycle ratings, paper

- Kauko K. (2012), Can Credit Risk Be Rated Through-the-Cycle?, Frontiers in Finance and Economics, Vol. 9 N°1, pp. 1-32

- Kiff J., Kisser M. and Schumacher L. (2013), Rating Through-the-Cycle: What does the Concept Imply for Rating Stability and Accuracy?, IMF Working Paper, WP/13/64

- Moody’s, Complementing Agency Credit Ratings with MIR® (Market Implied Ratings), Moody’s Analytics Credit research e risk measurement, http://www.moodysanalytics.com

- Petrov A. (2012), Implementing pit-ttc pd framework in credit risk classification system, presentazione Risk Minds 2012 Amsterdam, (slides)

- Rikkers F., Thibeault A. (2008), The influence of rating philosophy on regulatory capital and procyclicality, paper

- Rosch D. (2005), An empirical comparison of default risk forecasts from alternative credit rating philosophies, International Journal of Forecasting, Vol. 21, pp.37–51

- Standard & Poor’s (2014), Default, Transition, and Recovery: 2013 Annual Global Corporate Default Study And Rating Transitions, Standard&Poor’s Ratings Services, McGraw Hill Financial

- Topp R. and Perl R. (2010), Through-the-Cycle Ratings Versus Point-in-Time Ratings and Implications of the Mapping Between Both Rating Types, New York University Salomon Center and Wiley Periodicals

- Vallés V. (2006), Stability of a “through-the- cycle” rating system during a financial crisis, Financial Stability Institute, BIS, Award 2006 Winning Paper

[1] Aifirm ringrazia Silvio Cuneo e Giacomo De Laurentis (coordinatori del gruppo di lavoro) e Fabio Salis e Fiorella Salvucci

[2] Studies on validation of internal rating systems, The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, WP n. 14, May 2005, page 29.

[3] Idem, page 2.

[4] Idem, page 3.

[5] Ibidem.

[6] Idem, page 34.

[7] See Rosch. D. An empirical comparison of default risk forecasts from alternative credit rating philosophies, International Journal of Forecasting, 2005, page 47: “due to the lower asset correlation, the default distributions are in any case narrower under the Point in Time Rating scheme”.

[8] We will use the terms rating philosophy, degree of pitness and degree of cyclicality of ratings as synonyms.

[9] Positions on this issue are still dispersed. See for instance Rosch. D., 2005, page 38: “an exact definition of a Point in Time Rating is possible— it reflects a borrower’s 1-year probability of default—, while a definition of a Through the Cycle Rating is not as clear-cut”.

[10] Short for the document “International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards. A Revised Framework, Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, June 2004”.

[11] The observation period is the time length in which the default/non-default status of borrowers in the development dataset is observed. Let’s remember here again that paragraph 414 of Basel 2 regulation requires it should be longer than one year: “Although the time horizon used in PD estimation is one year (as described in paragraph 447), banks are expected to use a longer time horizon in assigning ratings”.