Executive summary

AIFIRM believes that the a Pillar 2 approach, where banks are allowed, subject to supervisory approval, to use internal measurement systems (IMS) for assessing their ability to cover potential losses from IRRBB, is the best suited option. In fact, the standardization associated with a Pillar 1 approach would lead to a lower precision of the risk exposure estimate and a poorer comprehension of the factors that determine it. By adopting a Pillar 1 approach, there is a higher probability that banks set aside an amount of internal capital that either underestimates or overestimates its appropriate amount, entailing a potential threat to the overall banking stability and an unnecessary reduction in lending capacity, respectively.

AIFIRM welcomes the consideration of multiple scenarios because it is a step forward in the comprehension of risk determinants. The new mathematical framework allows to obtain a measure of risk exposure that is more consistent with the level of interest rates observed on the evaluation date and, therefore, represents an important improvement, if compared with the current one, which is based on unrealistic duration coefficients. The new framework can also be easily integrated within banks’ IMS for the implementation of more sophisticated methodologies.

The Association believes that option n. 4 is the best-suited among those proposed by the Committee to calculate minimum capital requirements because it allows the net interest profit (NIP) to reduce minimum capital requirements associated with the change to economic value of equity (EVE) and earnings. This approach is based on the presence of many positions characterized by locked-in margins, which will generate a positive interest income even when EVE is at its highest. Following this method, minimum capital requirements are more consistent with banks’ actual riskiness and banks’ credit supply is calibrated in a more appropriate way. Within a Pillar 2 approach, minimum capital requirements may be based on both: i) stressed scenarios of changes in the key-rates that are consistent with the six proposed scenarios, in terms of both shock magnitude and structure, and ii) scenarios obtained through banks’ internal measurement systems. However, AIFIRM believes that further discussions and analyses on the NIP calibration are necessary.

As concerns the treatment of the items characterized by behavioral options, AIFIRM recognizes the utility of introducing some constraints in modelling non-maturity deposits (NMDs), even in cases of banks’ own internal representations, since they could contribute to the reduction of the model risk. However, they seem to be too conservative giving rise, even in the discretionary approach, to a unique representation of NMDs. According to AIFIRM, based on the analysis of historical data of the Italian banking market: i) the allocation of the repricing component of NMDs may be led by the interest rate pass-through that follows a change in the reference market rate; ii) the core component of NMDs should include not only the fraction of non-maturity deposits that are stable, but also the portion that reprice, with a certain sluggishness, when the reference market rate changes. Finally, as regards positions other than NMDs, the Association agrees with the choice to model their optionalities using a two step approach.

Within the supported solution of an enhanced Pillar 2 capital framework, AIFIRM believes that public disclosure on a regular basis of a bank’s IRRBB risk profile, key measurement assumptions, qualitative and quantitative assessment of IRRBB levels and quantitative disclosure of IRRBB metrics, is crucial. Banks should describe in detail the qualitative information required in BCBS (2015) for disclosure purposes since these are issues of particular relevance in estimating banks’ risk exposure. As for the quantitative information, if appropriate public disclosure is important, disclosure of standardized calculation could be misleading. By using the standardized calculation, the proposed Pillar 2 approach is no different from the proposed Pillar 1. Supporting a “true” Pillar II approach, AIFIRM believes that banks’ internal measurement and management of IRRBB are those which ought to be disclosed.

This document is organized as follows: paragraph 1 comments on the choice between a Pillar 1 and a Pillar 2 solutions; in section 2, we discuss some of the main issues associated with the interest rate scenario design; section 3 deals with the specification of minimum capital requirements; in section 4 we analyze the treatment of the positions with behavioral options; section 5 provides some comments on the disclosure requirements.

1. Pillar 1 vs. Pillar 2 approaches

AIFIRM believes that the most appropriate option is the enhancement of IRRBB measurement and management within the Pillar 2 because of the standardization of the measurement methodologies that would necessarily be required if the treatment of IRRBB were included in the Pillar 1. In fact, due to the differences in the risk estimates across various jurisdictions, that are mainly attributable to different business practices, interest rate volatility, balance sheet structures and financial market conditions, standardization would be needed to ensure greater comparability and a more level playing field. Nevertheless, standardization would lead to a lower precision of the risk exposure estimate and a poorer comprehension of the factors that determine it.

Due to standardization, estimates of IRRBB are more likely to be inconsistent with actual riskiness under a Pillar 1 approach, meaning that, relative to a Pillar 2 framework, there is a higher probability that banks set aside an amount of internal capital that either underestimates or overestimates its appropriate amount. In particular, errors in the estimates of IRRBB could represent a potential threat to the soundness of the single credit institution and to the overall banking stability. Whereas, in cases of underestimation, should the appropriate measure of internal capital be overestimated, banks require an excessive capital absorption, entailing an unnecessary reduction in their lending capacity and associated opportunity costs. It’s worth noting that a bank’s lending capacity is a multiple of the amount of its free capital, i.e., the difference between own funds and total internal capital. Therefore, the larger the internal capital that banks to set aside against IRRBB is, the lesser amount of loans they can grant.

Standardization may also provide useless or, even worse, misrepresented indications for ALM strategies to be implemented that could negatively affect banks’ risk taking behavior and performance. On one hand, an underestimation of the appropriate internal capital might drive managers to take excessive risk; on the other hand, an overestimation might prevent banks to implement ALM strategies that would improve their profitability and, via retained earnings, their capital endowment as well.

These issues are crucial from a global perspective, being of the utmost importance for banking systems, such as the Italian one, that are characterized by a large number of small and medium-sized banks, generally acting as qualitative asset transformers. For these banks, interest rate risk, which arises from the basic banking business, and the internal capital facing it, might be the second largest behind credit risk.

Therefore, it is AIFIRM’s strong conviction that a Pillar 2 approach, where banks are allowed, subject to supervisory approval, to use IMS for assessing their ability to cover potential losses from IRRBB, is the best suited option. Relative to a Pillar 1 approach, it would undoubtedly: i) ensure greater precision in the risk assessment process; ii) allow for a comprehensive investigation into the nature of banks’ risk exposure by shedding more light on the factors that determine it and iii) create the best conditions for risk takers to select the most appropriate ALM strategies.

Finally, even if AIFIRM strongly supports the adoption of an enhanced Pillar 2 capital treatment, the Association believes that the methodological framework specified by the Committee within the Pillar 1 option contains some interesting elements that could be useful from a Pillar 2 perspective as well, within banks’ internal measurement systems. In particular, the proposals concerning the implementation of different interest rate shock scenarios and the treatment of the optionalities embedded in various, major balance sheet items provide constructive indications for banks to develop well-grounded and effective internal models and should be carefully considered.

2. Interest rate shock scenario design

In this paragraph, we deal with some specific issues related to the interest rate shock scenario design. In particular, we discuss some of the main characteristics of the BCBS (2015)’s revision proposal and some technical issues that refer to the estimate of the global shock parameter.

2.1. Proposed shock scenarios and structure of the time bands

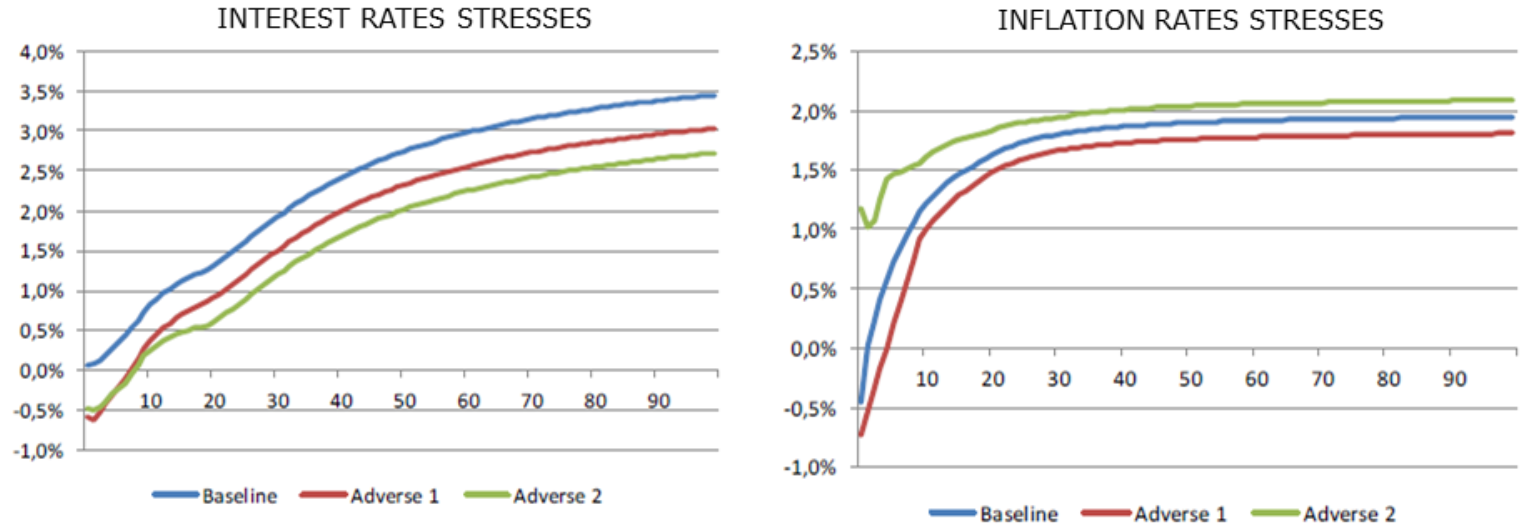

BCBS (2015) takes six interest rate shock scenarios into account, respectively represented by: i) parallel shock up, ii) parallel shock down, iii) steepener shock (short rate down and long rates up), iv) flattener shock (short rates up and long rates down), v) short rates shock up and vi) short rates shock down. The Committee also proposes the adoption of caps and floors to adjust in cases where an interest rate shock is above or below the bounds of possibility (prudence). Interest rate risk exposure is calculated through a new mathematical framework based on continuous compounding. According to this new framework, the change in a bank’s EVE is calculated by subtracting the EVE calculated by applying each of the six specific interest rate shock scenarios to the key-rates term structure from the EVE that is obtained by taking into account the term structure of key-rates observed on the evaluation date.

With the exception of parallel shocks up and down, the impact of the six interest rate shock scenarios depends on the number and boundaries of the time bands included in the maturity ladder. In fact, the structure of the time bands determines the global shock parameter, reflecting the average observed volatility across all currencies under interest rate shock scenario, and the scalar reflecting the characteristics of the shock scenario at each time bucket midpoint. In BCBS (2015), the number of the time bands has been increased from 14 to 19 and time bands have been classified in short- (from overnight to 2 years), medium- (from 2 years to 7 years) and long-term (from 7 years to more than 20 years).

In acknowledging the limits of the current regulatory framework, that have already been investigated by previous literature (Fiori and Iannotti, 2007; Entrop et al., 2008; Entrop et al. 2009; Cocozza et al., 2015a and 2015b), AIFIRM welcomes the consideration of multiple scenarios. These scenarios are a step forward in the comprehension of risk determinants and could help to prevent the risk-neutrality phenomenon[1] and address other issues of regulatory shock scenarios currently in force, as described in Annex 1. The new mathematical framework allows the user to obtain a measure of risk exposure that is more consistent with the level of interest rates observed on the evaluation date and, therefore, represents an important improvement, if compared with the current one, which is based on unrealistic duration coefficients. The new framework can be also easily integrated within banks’ internal measurement systems for the implementation of more sophisticated methodologies based on simulation techniques. The increase in the number of the time bands improves the accuracy of the estimate and the classification of time bands in short-, medium- and long-term and is useful for risk mapping, given the relationship between this classification and interest rate shock scenarios.

The structure of the time bands is a key-factor for the proper assessment of a bank’s IRRBB. AIFIRM welcomes the consideration of the opportunity to review the proposed classification in short, medium and long-term in order to make this classification more consistent with: i) the use, for the different nodes of the term structure, of monetary and interest rate swap (IRS) rates to calculate the net weighted positions; ii) the sign of the net positions observed in the time bands of Italian banks’ maturity ladder.

AIFIRM believes that the proposed classification of the time bands in short, medium and long-term can be improved in order to make the corresponding term structure of the net positions more homogeneous among these three types of time bands. This would presumably simplify the overall risk management process, by making risk mapping more efficient and straightforward.

On one hand, AIFIRM suggests the inclusion of those ranging from overnight to one year in the short-term time bands because this is the time horizon along which monetary rates are used in the current industry practice. In fact, banks usually adopt the EONIA (Euro Overnight Index Average) rate for the overnight time band, the Euribor rates for maturities shorter than 12 months, and IRS (Interest Rate Swap) rates for maturities longer than or equal to 1 year. On the other hand, AIFIRM has doubts about the lack of coincidence between the upper boundary of the medium-term (7 years) and the upper boundary of the time band up to which non-maturity deposits are distributed (“From 5 years to 6 years”).

Based on evidence (available upon request) which concerns a sample of 130 Italian credit institutions between 2006 and 2013, with the configuration of the time bands currently in force, AIFIRM expects net positions to be negative in the new medium-term time buckets, with the exception of the time bucket “From 6 to 7 years”. This would be due to the allotment of the core component of non-maturity deposits in the time bands up to 6 years[2] and of the fixed rate issued bonds with medium-term maturity. In the time bands ranging from 7 to 20 years, according to the Association, banks would, instead, be characterized by positive net positions, mainly stemming from the allocation of capital repayment of fixed rate loans and of the book value of fixed rate securities.

Should the upper boundary of the medium-term coincide with the upper boundary of the time band up to which non-maturity deposits are distributed, net positions in both medium- and long-term time bands would be homogeneous in terms of sign (negative and positive, respectively). It is AIFIRM’s opinion that this point deserves further analysis.

Finally, as concerns the introduction of caps and floors to the changes in the key-rates, AIFIRM believes that, in addition to the non-negativity constraint, it could be appropriate not to add any other restriction, in order to afford the key-rates the freedom to change. Both historically distant and recent episodes, such as the slope inversion that caused the savings and loan crisis in the U.S.A. back in the late ‘80s, or the exceptionally low level of the current market rates, have shown that the key-rates’ term structure can assume characteristics and dynamics which, ex ante, would have been deemed unrealistic.

2.2. Further technical issues

According to BCBS (2015), the interest rate shock scenario can be decomposed into the product of three elements: a measure of local current risk-free, continuously compounded zero coupon rates, a scalar reflecting the characteristics of the shock scenario representation at each time bucket midpoint and a global shock parameter, that reflects the average observed volatility across all currencies under a specific representation of the shock scenario. The global shock parameter is calculated through the percentiles method, which is applied to data which refers to a time horizon ranging from January 2000 to April 2014, and a six-month holding period.

In this paragraph, we shall discuss three main technical elements of the new interest rate shock scenario design: i) the adoption of the percentiles method (1st and 99th) to proxy for the relevant interest rate shock; ii) the overlapping technique that is used to obtain the distribution of the changes in the key-rate, and; iii) the six-month holding period for the interest rate shock calibration to be suitable for IRRBB capital purposes. Based on BCBS (2015), these three elements determine the global shock parameter and, ultimately, contribute to generate the interest rate shock.

The comments concerning the holding period and overlapping technique are important not only from the perspective of a proper estimate of the global shock parameter within the new interest rate shock scenario design, but, in more general terms, for the design and implementation of more advanced methodologies to generate interest rate shock scenarios, such as those based on historical and Monte Carlo simulations proposed below.

2.2.1. Percentiles method

AIFIRM believes that it is necessary to take some drawbacks of the adoption of the percentiles method into account. This method accounts for changes which have actually occurred in the key-rates. However, as already indicated above, these changes may have taken place on different days across the nodes of the key-rates term structure. This method, therefore, does not allow for the capture of the correlation empirically observed among these changes.

Designing the interest rate shock scenario based on the percentiles method may be affected by the following, second drawback. The percentiles may remain constant for long time and, then, suddenly change because of not only the introduction of new data, but, as time goes by, because of the removal of old data from the rolling window. While the first change in the percentile estimate is justified, the second one is not. In fact, if we think about the distribution of the changes in a particular key-rate, when a specific shock is dropped from the sample, it is likely that no significant innovation has affected the distribution.

The percentiles are calculated on the basis of a long observation period ranging from January 2000 to April 2014. According to the Basel Committee, a long observation period can warrant some stability in the international standard. However, this could lead to an estimate of the risk exposure that doesn’t correspond to the financial market’s condition observed on the evaluation date. In other words, a long time series of data gives stability to the estimates, but makes them less consistent with the financial market’s context as of the evaluation date. Conversely, a short time series of data could make the estimate of the risk exposure and the associated internal capital more realistic, because it is based on data closer to the evaluation date, but it may also be more volatile.

From a risk management perspective, consistent with the adoption of a Pillar 2 approach, AIFIRM believes that the percentiles method cannot be the only methodology used in order to estimate interest rate risk exposure, owing to the above mentioned drawbacks. However, the Association recognizes that it could be used for calculating interest rates shock scenarios that should be compared with those obtained through other more advanced methodologies within banks’ internal measurement models (see Annex 2 for the proposal of two advanced methodologies).

AIFIRM has doubts about the opportunity to use a 14-year time horizon to assess global shock parameters. In this regard, the current regulatory framework requires a five-year historical observation period (six years of data) to generate the interest rate shock, since, according to BCBS (2004), a five-year observation period can capture more recent and relevant interest rate cycles. The Association supports further analyses aimed at investigating the criteria to identify the length of the time horizon that ensures the best solution to the trade-off between stability and responsiveness to current market conditions. It is AIFIRM’s opinion that the global shock parameters should be updated over time, based, for example, on a rolling window, in order to measure the sensitivity of a bank’s equity through adaptive and forward looking interest rate shock scenarios that are able to consistently capture interest rates dynamics over time.

The global shock parameters for a single currency are simple averages of the 99th and the absolute value of the 1st percentile for all the tenors set by the Basel Committee, in the case of the parallel shifts, and, separately, for the short- and long-term tenors of the yield curve for the rest of the interest rate shock scenarios. AIFIRM questions whether or not it is more appropriate to estimate the global shock parameters by alternatively considering the 99th and the 1st percentile, depending on whether or not the interest rate shock scenario taken into account is, respectively, characterized by an increase or a decrease in interest rates. For example, in the case of the steepener (flattener) shock proposed by BCBS (2015), where short (long) rates decrease and long (short) rates go up, the downward (upward) shock in the short-term time bands could be measured by only referring to the absolute value of the 1st (99th) percentile, while the upward (downward) shock in the long-term time bands might be calculated by exclusively accounting for the 99th (1st) percentile.

2.2.2. Holding period

BCBS (2015) has set a six-month holding period for the interest rate calibration to be suitable for IRRBB capital purposes, because most institutions appear to have the ability to adjust their asset/liability profile in a period much shorter than the one-year holding period currently in force. The Basel Committee has decided not to adopt an even shorter holding period, even if it would be reasonable from an individual bank perspective. Nevertheless, due to a systemic shock in interest rates, banks may look for the same type of instruments to hedge their positions and may not be able to change their asset/liability profile within the same short period and at the current costs.

AIFIRM believes that the ability and the speed at which a bank can modify its asset/liability profile depends, among the other things, on the nature of the items in its balance sheet. From this perspective, it is worthwhile, within banks’ banking book, to distinguish between the security portfolio and the rest of the balance sheet items, such as loans, deposits and issued bonds, which, for the sake of brevity, can be defined as “commercial portfolio”. A bank which is more heavily involved in the traditional banking business is characterized by a major weight of the commercial portfolio. Such a bank will probably find much greater difficulties in modifying its asset/liability profile both timely and efficiently, without the use of derivatives.

Generally, in order to achieve the target exposure to IRRBB, banks can use different strategies to modify their balance sheet structure in terms of both maturity and repricing date. For example, banks aiming to reduce their exposure to a parallel shock up or to a steepener shock should cut the share of long-term fixed rate loans in favour of loans with floating rates, due to the sign of the net positions resulting from both the current and proposed allotment criteria of balance sheet items in the time buckets of the maturity ladder. In the case of a parallel shock up, instead, interest rate risk exposure may be reduced by also shrinking the share of medium-term floating rate issued bonds in favour of fixed rate ones. However, the implementation of these strategies requires a considerable amount of time.

Alternatively, banks can hedge their risk exposure through interest rate derivatives. In particular, banks can hedge fixed rate loans by using amortizing interest rate swaps or fixed rate issued bonds by using interest rate swaps. As concerns loans, in general, banks design specific hedge strategies in which the item that has to be covered is composed of a set of loans with homogeneous characteristics in terms of duration, repayment schedule, contractual rate and type of borrower. Each item follows an amortization schedule which is the aggregation of the amortization plans of all the loans included in the item. On each aggregate amortization schedule, a single amortizing interest rate swap is calibrated. In order to hedge risks associated with issued bonds, banks generally design micro-specific hedge strategies, according to which each issued bond is associated with a single interest rate swap.

Compared with the previous on-balance sheet items restructuring, derivative-based hedging strategies can be implemented in a shorter period that has to be long enough to plan and test these hedging strategies and then negotiate, given the market conditions, derivatives at an acceptable cost.

2.2.3. Overlapping technique

In order to calculate the distribution of the changes in the key-rates, the BCBS (2015) proposes the use of the overlapping technique, according to which these changes are calculated by subtracting the rates recorded six months previously from the rates observed on a certain day of a given year.

The overlapping technique has the advantage of capturing extreme shocks within the desired percentile, thus addressing the fat tails issue (leptokurtosis) associated with the distribution of daily changes in interest rates. The ability to capture extreme shocks within the desired percentile is inversely correlated with the length of the holding period. The absence of the leptokurtosis issue is confirmed by the negative values of the kurtosis coefficients observed for main market rates (EONIA, Euribor and IRS rates) over the period 2001-2013 (available upon request).

On the other hand, the overlapping technique produces serially correlated observations. Therefore, it is reasonable to expect that the series of semi-annual changes in the key-rates are less volatile than a time series of a similar number of serially independent observations.

A possible alternative to the overlapping technique is to use daily observations and to apply the square root rule in order to transform the one-day holding period into the required six-month one. In this case, the time series would be leptokurtic even if Fiori and Iannotti (2007) show that this issue can be addressed by applying specific filters that modify the distribution of the daily changes in interest rates. These latter techniques, however, are rarely used in banking practice due to their excessive sophistication.

The square root rule presents two major drawbacks: on the one hand, it is based on the rather unrealistic hypothesis of serial independence of interest rate changes that is not consistent with the actual interest rates dynamics, and, on the other hand, estimates based on the square root rule lose their predictive power as the holding period increases.

Given the advantages and disadvantages associated with the different methodological options mentioned above (namely, the overlapping technique and the square root rule), it is AIFIRM’s opinion that the overlapping technique is the most appropriate solution for the definition of the regulatory interest rate shock scenarios, and can also be easily used by banks in advanced methodologies within internally modeled approaches, as those described below.

3. Specification of minimum capital requirements

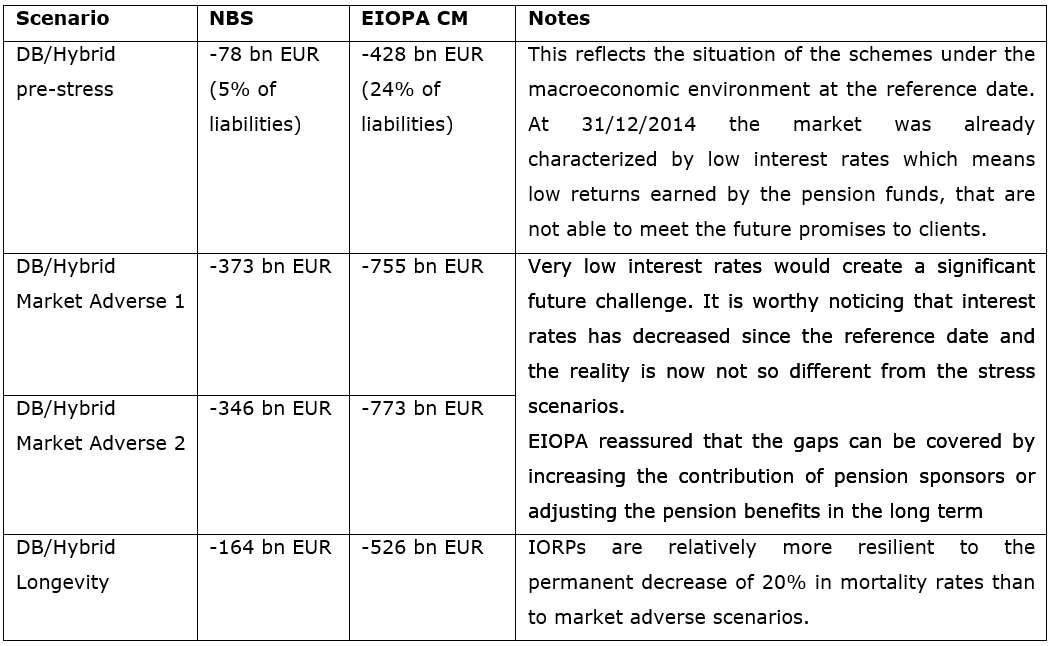

According to BCBS (2015), minimum capital requirements for IRRBB are measured based on the scenario that determines the largest decline in EVE and, where applicable, net interest income (NII), among the six prescribed interest rate shock scenarios. In particular, the Committee has set out four options to calculate minimum capital requirements under the Pillar 1 approach: the first option takes into account only the EVE measure whereas the other three incorporate, in various forms, the earnings overlay mechanisms to better reflect short-term risk. In particular, the fourth option considers the NIP accounting variable, which is a proxy for banking book earnings which are expected based on locked-in margins in the near future after adjusting for expenses and costs associated with banking book activities. The NIP functions as a risk-sensitive threshold, below which there are no capital requirements, because it is subtracted from the minimum capital requirements associated with the change to EVE and earnings. Furthermore, a specific rule is provided in order to take into account the exposure referred to different currencies.

AIFIRM recognizes the need for a criterion to determine minimum capital requirements that takes both EVE and NII approaches into account, based on their respective peculiarities. As to the relationship between these two different metrics, AIFIRM highlights that the empirical evidence obtained on a sample of 130 Italian banks over the period 2006-2013 (available upon request) generally shows a negative correlation between the EVE and NII metrics, where the former are calculated by considering both parallel shifts and percentiles method and the latter are measured through the repricing gap model with a one-year gapping period. The negative correlation is greater when the percentiles method is taken into account. Furthermore, it decreases over time, for both the parallel shifts and percentiles method, and takes positive values in the last two years of the time horizon that are characterized by exceptionally low interest rates. As regards the currency aggregation rule, AIFIRM agrees with the use of a precautionary approach, which is based on partial offsetting between reductions and increases in EVE and NII across different currencies.

As concerns the choice of the criterion to calculate bank internal capital against IRRBB, AIFIRM wonders whether or not the use of the scenario associated with the largest decline in EVE and, where applicable, NII, is the most appropriate one. This choice is certainly functional to ensure, from a micro perspective, a bank’s soundness and, from a macro perspective, the global financial stability thereof. However, at the same time, such a choice might have negative implications on banks’ credit supply.

Given this background, the Association believes that option n. 4 is the best-suited among those proposed by the Committee because it allows for the inclusion of future margin levels (NIP) in the minimum capital requirements calculation associated with the change to EVE and earnings. This approach is based on the presence of many positions characterized by locked-in margins, which will generate a positive interest income even when EVE is at its highest. Following this method, minimum capital requirements are more consistent with banks’ actual riskiness and banks’ credit supply is calibrated in a more appropriate way. However, AIFIRM believes that further discussions and analyses on the NIP calibration are necessary.

4. Treatment of positions with behavioral options

AIFIRM appreciates the classification of balance sheet items based on their amenability to standardization and the introduction of specific methodologies to model their embedded optionalities, since this leads to a greater understanding of the determinants of risk exposure.

4.1. Non-maturity deposits

The treatment of non-maturity deposits is one of the main areas of concern in measuring IRRBB. NMDs are characterized by: i) the absence of a contractual maturity and the associated depositors’ right to withdraw at any time; ii) the stability of a large part of their volume over time, due to a sufficient diversification of counterparties and iii) the partial and delayed reaction of the bank rate to the change in the reference market rates, due to banks’ rights to revise the financial conditions at their own discretion.

From an IRRBB management perspective, it is crucial to identify the aggregate balance of core NMDs and to appropriately slot them into the corresponding time buckets of the maturity ladder. BCBS (2015) proposes two alternative approaches to separate core and non-core cash-flows: the Time Series Approach (TIA) and a simplified TIA (STIA). Under the Time Series Approach (TIA), the Committee suggests, firstly, the distinction between stable and non-stable NMDs using the time series of their volumes over the past 10 years. Secondly, the stable portion is further broken down into a pass-through and non pass-through component. The former includes NMDs that reprice following a change in the reference market rates and is entirely allotted into the overnight time band. Consequently, the core component comprises those NMDs that are both stable and do not reprice over time. This core portion can be slotted following two alternative approaches: the “uniform” approach” (core deposits linearly allocated up to 6 years) and a “discretionary approach”, where core deposits could be allocated following some internal estimations with respect to the final maturity (6 years) and a constrained average life of three years. Under the simplified TIA (STIA), banks can use two alternative criteria: i) NMDs are segmented into retail and wholesale deposits and core NMDs are calculated as a proportion of total NMDs based on one year of banks’ internal data on NMD balance subject to the caps set by the regulator; ii) NMDs are segmented into retail and wholesale deposits and, according to the deposit volume per depositor, are based on eligibility coefficients set by the regulator.

The absence of a contractual maturity, and a banks’ option to discretionally change the interest rate paid to depositors, would suggest that NMDs are allotted into the overnight time bucket of the maturity ladder. Nevertheless, the sluggish and partial reaction of the NMD rates to changes in the reference market rates would imply a different treatment.

The proposed standardized treatment of NMDs, which is constrained by both the pass-through floors and stability parameters and maximum maturities of core NMDs, is far too restrictive and does not enable a realistic representation of the interest rate sensitivity of deposits. AIFIRM recognizes the utility of introducing some constraints in modelling NMDs, even in case of banks’ own internal representations, since they could contribute to reduce the model risk. However, they seem to be too conservative giving rise, even in the discretionary approach, to a unique representation of NMDs. The 60% implied cap for transactional retail deposits (even less for non-transactional retail deposits and for corporate ones), together with the maximum maturity of 6 years and average life of 3 years for only the “core” portion lead to a single and unique slotting, that is the standardized one (the uniform approach). There is no room for internal model adoption unless they are even more conservative than the standardized approach in terms of maturity, duration and portion to be allocated o/n. It would be worthwhile to have some constraints in terms of risk (e.g. overall duration).

According to AIFIRM, based on the analysis of historical data of the Italian banking market: i) the allocation of the repricing component of NMDs might be led by the interest rate pass-through that follows a change in the reference market rate; ii) the core component of NMDs should include not only the fraction of non-maturity deposits that are stable, but also the portion that reprice, with a certain sluggishness, when the reference market rate changes.

As concerns this latter issue, Cocozza et al. (2015a) propose to model the repricing profile of NMDs through an error correction model based on the logic highlighted below. The repricing NMDs are assumed to be a percentage of the total amount, which is given by the cointegration parameter measuring the degree of pass-through in the long term. This parameter is identified by analyzing the long-term relationship between the bank rate and the reference market rate. Based on the structure of the short-term repricing delays, estimated through a unit response function, the Authors calculate the set of the so called “repricing coefficients”. These coefficients are applied to the amount of the pass-through component of NMDs in order to break them down further and slot them within the appropriate time buckets of the maturity ladder.

The methodology proposed by Cocozza et al. (2015a) provides a comprehensive analysis of the main issues associated with NMDs’ behavior, in terms of both their repricing mechanism and volume decline over time, since it also takes into account this latter aspect through the so called “decline coefficients”. In particular, decline coefficients are calculated by: i) analyzing a lognormal transformation of the time series of NMD volumes, in order to model the decline profile according to an exponential function that makes non-maturity deposits converge to zero without taking negative values; ii) adapting the framework used by Dowd (2005) to estimate a lognormal VaR under a parametric approach to our case, where the risk factor is the cyclical component of non-maturity deposits instead of the change in asset price. Both repricing and decline coefficients are used to calculate some allotment coefficients that are applied to the volume of NMDs to allocate them across the time buckets of the maturity ladder. Consistent with the adoption of a stress scenario, one can assume that the amount of deposits to be repriced does not decline and vice versa.

It is AIFIRM’s opinion that behavioral models, such as the one proposed in Cocozza et al. (2015a), could provide crucial indications for the treatment of NMDs. In particular, according to AIFIRM, supervisory authorities may make their own estimates of the final allotment coefficients based on system-wide data available. This would allow for the replacement of methods deemed “too simplistic” to allot core NMDs, such as the uniform approach proposed in BCBS (2015), that fail to adequately consider these deposits’ actual behavior.

AIFIRM has promoted the analysis of the sluggishness of bank interest rates in the context of very low market rates and its implications from a risk management perspective. Parisi et al. (2015) develop an enhanced version of the error correction model that allows for the assessment of predictive performance, as well as an alternative, simpler-to-interpret model, that actually improves predictive performance. They show that when rates are close to zero, as has been seen in recent years, administered interest rates are not at all affected by monetary rates, but they depend only on their past values. The Authors also contributed to the interest rate risk literature by suggesting a forward-looking method to allocate non-maturity deposits to non-zero time maturity bands, according to the predicted bank rates. Overall, this study reveals that bank rates’ sluggishness has undergone radical changes in the last period characterized by low levels of interest rates. Hence, AIFIRM believes that it is crucial to have an updated estimate which does not suffer from excessive volatility of the fundamental risk parameters and allows for the capture of their actual dynamics.

As already mentioned above, under the TIA, banks have to estimate stable NMDs as a portion of total NMDs by using observed volume changes over the past 10 years. Whereas, under the simplified TIA (STIA), credit institutions estimate core NMDs based on 1 year of internal data on NMD balance. In recognizing the importance of a sufficiently long time series of data to provide adequate estimates of the stable/core portion of NMDs, AIFIRM has questions regarding possible drawbacks stemming from the difference in the length of the two time periods (10 years vs. 1 year). In fact, due to the lower historical depth of the time series used to estimate core NMDs under the STIA, the estimates could be affected by a higher volatility, relative to those coming from the adoption of the 10-year time horizon under the TIA. This issue would especially concern small and medium-sized banks that are more likely to adopt the STIA, since they are not expected to have the capacity to fully develop the analysis required by the TIA. According to AIFIRM, this may be an undesired result of the proposed regulatory discipline that: i) constitutes a significant bias in the regulation, entailing a disparity of treatment between large banks and small and medium-sized credit institutions and ii) neglects the greater stability of the deposits characterizing the latter group of banks, which is due to their stronger relationship with local customers.

4.2. Positions with behavioral options other than NMDs

The adequate modeling of the behavioral options embedded in fixed rate loans with prepayment risk, fixed rate loan commitments and term deposits subject to early redemption risk, is both crucial and challenging for Italian banks, also due to the trends observed in the recent years in the Italian banking system, especially with regard to fixed rate loans. In fact, incentives for the exercise of the prepayment option for fixed rate loans have strongly increased because of: i) a change in the Italian regulation which came into force in 2007, which, for some types of loans, removed the penalties for those borrowers that repaid their loan early and chose transfer it to another bank and, in more recent years, because of ii) the exceptionally low interest rates.

As concerns deposits with redemption risk, it is important to highlight that, although they are not a significant share of Italian banks’ liabilities, they have experienced a robust increase during the financial crisis as a result of the changes in banks’ funding strategies, aimed at maximizing the stability of their sources of funds.

AIFIRM agrees with the choice to model the optionalities of these accounts using a two-step approach. The estimate of baseline parameters (the conditional prepayment rate for the fixed rate loans with prepayment option (CPR), the pull through ratio (PTR) for fixed rate loan commitments and the term deposit redemption rate (TDDR) for the term deposits) and the correction for the scalar reflecting the likely behavioral changes in the exercise of the options, given a particular interest rate shock scenario, increases the accuracy of the risk exposure estimate.

Overall, the methodology is simple and adaptable to implement for banks. Banks that will be able to internally estimate the baseline parameters and the scalar should make risk exposure estimates more consistent with their actual riskiness, relative to banks that use the parameters provided by supervisors. Nevertheless, the former might bear a significant computational burden since they should divide, on the asset side, their portfolios of fixed rate loans and fixed rate loan commitments and, on the liability side, the term deposits, into homogeneous clusters and manage them over time in order to produce consistent estimates of the baseline parameters and scalars.

The modeling of the prepayment option has been investigated by prior literature[3], while, to the best of our knowledge, the options embedded in term deposits with redemption risk and fixed rate loan commitments have not been yet examined by significant, previous studies that adopt an IRRBB management perspective and deal with the associated regulatory issues. The Association strongly encourages further analysis on these specific issues.

5. Disclosure

Within the supported solution of an enhanced Pillar 2 capital framework, AIFIRM believes that public disclosure on a regular basis of a bank’s IRRBB risk profile, key measurement assumptions, qualitative and quantitative assessment of IRRBB levels and quantitative disclosure of IRRBB metrics, are crucial. It is AIFIRM’s conviction that an appropriate level of timely disclosure will provide benefits for well-run banks, investors and depositors, and will contribute to ensure general financial stability and to support the effective and efficient operations of the capital markets, from a broader perspective.

Banks should describe in detail the qualitative information required in BCBS (2015) for disclosure purposes since these are issues of particular relevance in estimating banks’ risk exposure. As for the quantitative information, if appropriate public disclosure is important, disclosure of standardized calculation might be misleading. By using the standardized calculation, the proposed Pillar 2 approach is not different from that of Pillar 1. In supporting a “true” Pillar 2 approach, AIFIRM believes that banks’ internal measurement and management of IRRBB should be the ones to be disclosed. Furthermore, AIFIRM suggests to report not only the increase/decline in economic value and earnings, corresponding to each interest rate shock scenario and based on the bank’s internal measurement systems, but also the term structure of bank’s net positions. Given the interest rate shock scenario, it can provide an immediate view of possible imbalances affecting the term structure of the bank’s balance sheet.

In addition, it is desirable that the latter is broken down into macro accounting aggregates with evidence of the securities held in the banking book and derivatives used for hedging purposes. This would allow for identification of the impact of these items on the bank’s risk exposure. Furthermore, AIFIRM queries the opportunity that banks provide details on the allotment into the maturity ladder of the balance sheet items that are characterized by embedded optionalities (i.e., how non maturity deposits are distributed across the time buckets of the maturity ladder).

Annex 1. The limits of the current regulatory interest rate shock scenarios

Based on BCBS (2004), Bank of Italy (2013) requires to estimate interest rate risk exposure by applying a standardized shock to the term structure of the key-rates associated with the 14 time bands of the regulatory maturity ladder. This standardized shock can be alternatively given by a ± 200 basis point parallel shift in the yield curve fixed for all maturities (from here on, the parallel shifts method) or by the 1st and 99th percentile of observed changes in the key-rates, using a one year holding period and a minimum five years of observations (from here on the percentiles method). According to the current regulatory treatment, based on the so called non-negativity constraint, the applied shock cannot drive the key-rates term structure below the zero level. These two regulatory scenarios show some major issues that are presented in the rest of this paragraph, before discussing some of the main aspects of the interest rate shock scenario design proposed in BCBS (2015).

The parallel shift is set regardless of the changes in the key-rates actually observed, whereas the percentiles method is based on the distribution of actual changes of the key-rates term structure. Nevertheless, since the changes corresponding to the 1st percentile of the distribution might have occurred on different days for the various nodes of the term structure (for example, on January 22nd, 2014 for the key-rate of the first time band, on December 23rd, 2013 for the key-rate of the second time band, etc.), this method does not account for the actual correlations among the annual changes in the key-rates.

Both of the above mentioned methodologies measure interest rate risk exposure via unrealistic duration coefficients, which are based on a flat term structure of interest rates, that are set equal to 5%. The drawbacks associated with these duration coefficients have been investigated by Fiori and Iannotti (2007). In particular, the Authors develop a Value at risk (VaR) methodology to modeling interest rate changes, which is able to account for both asymmetry and kurtosis of their distribution. Based on the evidence which concerned 18 major, large and medium-sized Italian banks under the parallel shifts method, the Authors found that, if the duration coefficients set by the Committee are calibrated through the market data observed on the evaluation date, their results are consistent with the estimates of risk exposure.

Under both the parallel shifts and percentiles method, the estimate of a bank’s risk exposure is obtained by assuming that all the key-rates move together in the same direction. However, banks are exposed to a wide set of adverse scenarios that can be characterized by changes with different signs and magnitude across the 14 nodes of the key-rates term structure.

Annex 2. A methodological proposal: two advanced methodologies to simulate interest rate shock scenarios

Here, AIFIRM proposes two advanced methodologies that are based on simulation and overlapping techniques and overcome the limits highlighted before. The first one makes use of historical simulations and calculates a bank’s risk exposure by using interest rate shock scenarios represented by the key-rates joint semi-annual changes that actually occurred on each of the days included in the prescribed, past time horizon. Each scenario is added to the key-rates observed on the evaluation date and the new key-rates term structure is applied to the bank’s net positions in order to get the net weighted positions. Then, we sum the net weighted positions to obtain the bank’s EVE under the specific interest rate shock scenario and subtract it from the EVE under the current key-rates term structure to get the bank’s change in EVE. By repeating this procedure for all the days included in the time horizon we get the empirical distribution of the bank’s changes in EVE and cut it in correspondence of the percentile associated with the desired confidence level, set equal to 99%, following BCBS (2004). Nevertheless, it is important to note that during periods of low interest rates, such as the current one, the non-negativity constraint may prevent this method from capturing the correlations, just like in the parallel shifts and percentiles methods.

Our second advanced method is based on Monte Carlo simulations and allows for the generation of scenarios that both take into account the correlations between the semi-annual changes in our key-rates and meet the non-negativity constraint. We carry out as many simulations as those required to obtain the desired number K of scenarios and reject those simulations leading the term-structure of our key-rates under the zero level in one or more nodes. In this way, we get a distribution of the changes in EVE which is cut at the 99th percentile. In particular, the methodological proposal is developed along the following steps:

i) selecting the joint probability density function that guarantees the best approximation of the actual distributions of the semi-annual changes in the key-rates. The application of the overlapping data technique should make the use of a normal joint probability density function well-grounded, which can be also easily implemented by banks. Fiori consultative document “Interest rate risk in the banking book”and Iannotti (2007) confirmed the opportunity to adopt such distribution for annual changes in the key-rates. Further analyses are required for the semi-annual changes;

ii) estimating means and variances of the distributions of the semi-annual changes in the key-rates, as well as their variance-covariance matrix (Ω). Distributions of semi-annual changes are not adjusted on the basis of the non-negativity constraint in order to account for actual correlations among the changes in key-rates;

iii) generating a random number ui (i=1,…19) ranging from 0 to 1 at each node of our key-rates term structure;

iv) converting each ui obtained in the previous point iii) into a value zi (i=1,…19) distributed according to a standard normal. In symbols:

where F -1 is the inverse of the distribution function of the probability density function of the semi-annual changes of the i th key-rate;

v) using the algorithm of Cholesky in order to decompose the matrix Ω in two matrices Q and Q’ such that:

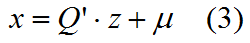

vi) calculating the vector x, whose elements are the joint simulated semi-annual changes in the key-rates through the following formula:

where z is the vector of the values calculated in step iv) and m is the vector of the 19 means of the distributions of the key-rates semi-annual changes. Each vector x represents a simulated scenario that will be used to calculate the risk indicator;

vii) repeating steps iii) to vi) until reaching a number K of scenarios that meet the non-negativity constraint. In fact, we only consider those scenarios meeting the non-negativity constraint for each node of our key-rates term structure;

viii) each of the K simulated scenarios is added to the key-rates observed on the evaluation date and the new key-rates term structure is applied to the bank’s net positions to get the weighted net positions, which are then summed to obtain the bank’s EVE under the specific interest rate shock scenario. This is later subtracted from the EVE under the current key-rates term structure to get the associated bank’s change in EVE. By repeating this procedure for all the K scenarios, we get the empirical distribution of the bank’s change in EVE, which is then cut in correspondence of the percentile associated with the desired confidence level, set equal to 99%, following BCBS (2004).

In order to consider interest rate shock scenarios with specific characteristics, without neglecting the correlations between the various nodes of the key-rates term structure, the simulations could be constrained within specific intervals with the desired range of magnitude and/or sign, depending on the specific nodes of the term structure. In detail, the upper and lower boundaries of a specific interval are calculated by adding the desired shock to the key-rate term structure observed on the evaluation date. In addition, the lower boundary has to be calibrated in order to meet the non-negativity constraint. In order to measure a bank’s risk exposure, it is necessary to repeat steps from iii) to vi) until reaching a number K of scenarios that lie within the above mentioned interval and then apply step viii).

References

- Bank of Italy, (2013). Regulation of the prudential supervision of banks. Directive No. 285/2013.

- Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, (2004). Principles for Management and Supervision of Interest Rate Risk, Bank for International Settlements.

- Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, (2015). Interest rate risk in the banking book. Consultative document, Bank for International Settlements, June.

- Black F., Derman E. and Toy W. (1990), A One-Factor Model of Interest Rates and Its Application to Treasury Bond Options, in Financial Analysts Journal , Vol. 46, N. 1, pp. 33-39.

- Cocozza, R., Curcio, D., Gianfrancesco, I., (2015a). Non-maturity deposits and banks’ exposure to interest rate risk: issues arising from the Basel regulatory framework. Journal of Risk, 17(5), 99-134.

- Cocozza R, Curcio D, Gianfrancesco I. (2015b), Estimating bank’s interest rate risk in the banking book: a new methodological framework beyond the current regulatory framework, CASMEF (Centro Arcelli per gli Studi Monetari e Finanziari) Working Paper series, no. 4, University LUISS Guido Carli, Rome.

- Dowd, K. (2005). Measuring Market Risk. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons.

- Entrop, O., Memmel, C., Wilkens, M., and Zeisler, A., (2008). Analyzing the interest rate risk of banks using time series of accounting-based data: evidence from Germany. Deutsche Bundesbank Discussion Paper Series 2 No. 1.

- Entrop, O., Wilkens, M., Zeisler, A., (2009). Quantifying the Interest Rate Risk of Banks: Assumptions Do Matter. European Financial Management 15(5), 1001–1018.

- Fiori, R., Iannotti, S., (2007). Scenario Based Principal Component Value-at-Risk: An Application to Italian Bank’s Interest Rate Risk Exposure. Journal of Risk 9(3), 63–99.

- Parisi L., Gianfrancesco I., Gilberto C. e Giudici P. (2015), Monetary transmission models for bank interest rates, Working Paper n.101, Department of Economics and Management, Università degli Studi di Pavia.

- Richard S.F., Roll R. (1989), Prepayments on fixed-rate mortgage-backed securities, in The Journal of Portfolio Management, Vol. 15, N.3, pp.73-82.

- Schwartz E.S., Torous W.N. (1989), Prepayment and the Valuation of Mortgage-Backed Securities, in The Journal of Finance, Vol. XLIV, N. 2., pp.375-392.

Le opinioni riportate nel presente documento sono proprie di AIFIRM e degli autori e non vincolano in alcun modo le istituzioni di appartenenza degli stessi autori

[1] Based on the evidence referred to a sample of 130 Italian banks over the period 2006-2013, Cocozza et al. (2015b) show that, when market rates are quite low, the regulatory methodologies might lead to an unrealistic conclusion about banks’ risk exposure: some banks, which the Authors define as “risk-neutral” credit institutions, appear to experience a raise in their EVE, whether interest rates decrease or increase. The non-negativity constraint is responsible for the risk-neutrality phenomenon. In detail, under the current regulatory framework, by applying a -200bp parallel shock not adjusted to account for the non-negativity constraint, a bank exposed to decreasing interest rates would experience a reduction in the EVE that would be equal, in absolute value, to the increase associated with a +200bp parallel shock. Actually, when the parallel scenario of -200bps is adopted, the non-negativity constraint can weaken the reduction associated with the negative net positions arising in the time bands ranging from 1 to 5 years, where, on average, rate-sensitive liabilities are greater than rate-sensitive assets, mainly because of the allotment of non-maturity deposits. This can make the bank risk-neutral.

The same logic can be easily extended to the percentiles method, though Cocozza et al. (2015b) show that, under this latter method, risk-neutrality can occur also in periods that are not characterized by low interest rates, even if with a lower frequency. When it does not depend on the non-negativity constraint, risk-neutrality is caused by the combined effect of the particular scenarios of changes in the key-rates and the specific structure, in terms of both sign and size, of some banks’ net positions across the time bands of the regulatory maturity ladder.

[2] We have not quantified the core component of NMDs, but the larger it is, the more likely to occur is the scenario we describe in the text.

[3] Generally, the estimate of prepayments can be made by using two different approaches: on the one hand, there are models based on financial options valuation techniques and, on the other hand, there are models founded on the analysis of a set of explanatory variables that we define as empirical models. The former group of models examines the dynamics of the beta of the embedded options, which can be considered as a proxy of the probability of early repayment at different maturities (Black et al., 1990). Nevertheless, results stemming from the models based on the valuation of the embedded options are not generally consistent with actual borrowers’ behavior. In fact, due to their lack of expertise and technical knowledge, borrowers do not ground their actions on a proper analysis of the convenience to exercise the embedded option.

Empirical models estimate a prepayment rate which is the share of the total loan amount which will be repaid on different maturities. In order to determine this share of prepayment, Richard and Roll (1989) adopt a specific model based on three factors: i) the refinancing incentive based on the ratio of the borrowers’ coupon payment to the current mortgage rate; ii) the seasoning or the age of the mortgage and iii) the month of the year (seasonality). Models based on the survival analysis framework are usually included into the empirical models too. Particularly, based on historical prepayment rates, these latter estimate a survival function, whose application allow to assign notional repricing cash flows to the time buckets according to the probability of prepayment events (Schwartz and Torous, 1989).