Sono stati rivisti gli standard per le richieste di informativa del Terzo Pilastro. Tali modifiche entreranno in vigore a fine 2016.

Il Comitato di Basilea ha pubblicato il secondo report sull’implementazione delle norme per la raccolta dati e il reporting sul rischio. Le G-SIBs dovranno implementare le nuove norme entro il 2016.

1. La crisi e l’imposizione del cambio fisso

Una delle classiche conseguenze delle crisi economiche è la fuga dagli investimenti ‘rischiosi’ in direzione dei safe havens, paradisi sicuri in cui depositare la propria liquidità in attesa della fine delle incertezze sui mercati finanziari e nell’economia reale. La crisi del 2007-09 non ha rappresentato un’eccezione: il ripiegamento degli investitori si è tradotto in massicci investimenti in oro, la cui valutazione è aumentata dai 484 dollari/oncia di giugno 2007 a circa 1300 a settembre 2011[1], e in valute rifugio, quali il dollaro statunitense e il franco svizzero (di seguito, semplicemente franco). Gli acquisti di valuta elvetica, in particolare, hanno portato a un deciso apprezzamento del franco, il cui cambio con l’euro è diminuito da 1,65 CHF/EUR (gennaio 2008) a 1,48 (gennaio 2010), sino alla quasi parità ad agosto 2011 (grafico 1).

I chiari rischi di deflazione e di recessione, questi ultimi ancora più significativi se si considera che l’economia svizzera aveva superato quasi senza problemi la crisi e che il PIL, sebbene rallentato, aveva avuto crescita negativa solo nel 2009, hanno dunque spinto la banca nazionale svizzera (BNS) a fissare nel mese di settembre 2011 il tasso di cambio a 1,20 CHF/EUR, con possibilità di azioni per svalutare ulteriormente la moneta nazionale. Tale obiettivo veniva perseguito secondo la consolidata tecnica di stampa di moneta e vendita di attività in franchi e acquisto potenzialmente illimitato di attività in valuta straniera (BNS, 2011a; BNS, 2011b; BNS, 2014a; Monacelli, 2015).

La strategia della BNS ha garantito che il tasso di cambio non superasse al ribasso la soglia prevista, fluttuando nel periodo settembre 2011 – novembre 2014 tra 1,20 e 1,25 CHF/EUR (grafico 1). A dicembre, alle operazioni di mercato aperto è stata aggiunta l’imposizione di un tasso di interesse negativo sui depositi pari allo 0,25%, in vigore dal 22 gennaio di quest’anno; l’obiettivo è il mantenimento del LIBOR in una fascia compresa tra -0,75% e 0,25%. È prevista una soglia di esonero per l’applicazione del tasso negativo pari a 10 milioni di franchi, inoltre la soglia per le banche obbligate a detenere riserve presso la BNS è di 20 volte i requisiti minimi (Monacelli, 2015; BNS, 2014b).

Grafico 1

Fonte: Banca d’Italia

2. L’interruzione del cambio fisso: motivazioni e conseguenze

Il 15 gennaio la BNS ha deciso di sospendere la fissazione del tasso di cambio minimo; al fine di limitare l’apprezzamento del franco e il peggioramento delle condizioni di credito, i tassi di interesse sui depositi sono stati abbassati di mezzo punto, così come gli obiettivi del LIBOR (BNS, 2015).

Tre sono le motivazioni principali che possono spiegare la decisione della banca centrale. Innanzitutto, come evidenziato dai vertici della stessa istituzione, il brusco calo del tasso di cambio euro-dollaro ha reso il franco troppo debole nei confronti della valuta statunitense. Ben più importanti, però, sono i restanti due motivi.

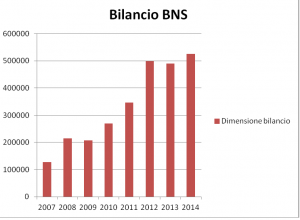

Nel corso del 2014 ulteriori incertezze economiche e geopolitiche, tra cui la caduta del prezzo del petrolio e la fuga di capitali dal rublo per la crisi russa, hanno contribuito a rafforzare il ruolo del franco come bene rifugio. La politica della BNS, come detto, prevedeva operazioni di acquisto di attività in valuta diversa dal franco: ciò ha enormemente ampliato il suo bilancio, sino agli attuali 525 miliardi di franchi (vedi grafico 2). A seguito di ciò sono emerse difficoltà sul controllo del bilancio stesso, nonché valutazioni politiche circa il ruolo della BNS; inoltre le buone condizioni dell’economia (con tassi di crescita attorno al 2%) non giustificavano misure eccezionali a difesa del cambio (verso possibili apprezzamenti).

La mossa dell’istituto elvetico ha rappresentato un ulteriore indizio circa l’imminenza dell’approvazione del QE da parte della BCE. Le nuove misura di politica monetaria non convenzionale dell’istituto di Francoforte avrebbero infatti portato incontrollabili movimenti di mercato con un’ingente immissione di euro in circolazione, flussi di capitale in uscita dall’euro, ulteriore svalutazione dell’euro e delle attività detenute dalla BNS (BNS, 2014c; BNS, 2015, Monacelli, 2015).

Grafico 2

Fonte: Banca Nazionale Svizzera, Monthly Bullettin.

Gli esiti dell’abbandono del cambio fisso non sono del tutto chiari. Il rafforzamento della moneta colpirà duramente l’economia nazionale: si stima un calo di 5 miliardi dell’export e una diminuzione dello 0,7% del PIL. La nuova, inattesa, ventata di instabilità proveniente dal paese elvetico ha ulteriormente spinto gli investitori verso impieghi sicuri, come l’oro, le cui valutazioni sono aumentate a seguito della scelta della BNS (si veda la nota 1), e la corona danese. L’autorità danese, pur trovandosi di fronte a rischi simili a quella svizzera, non ha abbandonato il tasso fisso, bensì ha abbassato tutti i tassi di interesse di riferimento di 15 punti base, riportando il tasso sui depositi a -0.2% (sul tema si veda Corsaro, 2014).

Ulteriori mosse da parte della BNS non sono facilmente prevedibili, molto dipenderà dall’andamento dell’economia nazionale e dai volumi di acquisti e modalità operative del QE europeo. Date le modeste dimensioni dell’economia svizzera, non vi saranno invece reazioni rilevanti per l’euro e l’eurozona.

Bibliografia

Banca Nazionale Svizzera (BNS ). Short statement by Philipp Hildebrand on 6 September 2011 with regard to the introduction of a minimum Swiss franc exchange rate against the euro. Discorso. 2011b.

http://www.snb.ch/en/mmr/speeches/id/ref_20110906_pmh/source/ref_20110906_pmh.en.pdf

Banca Nazionale Svizzera (BNS). SNB balance sheet items end of November 2014. 2014c.

http://www.snb.ch/ext/stats/balsnb/pdf/deen/Bilanz_der_SNB.book.pdf

Banca Nazionale Svizzera (BNS). Swiss National Bank discontinues minimum exchange rate and lowers interest rate to –0.75%. Comunicato stampa. 2015.

http://www.snb.ch/en/mmr/reference/pre_20150115/source/pre_20150115.en.pdf

Banca Nazionale Svizzera (BNS). Swiss National Bank introduces negative interest rates. Comunicato. 2014b.http://www.snb.ch/en/mmr/reference/pre_20141218/source/pre_20141218.en.pdf

Banca Nazionale Svizzera (BNS). Swiss National Bank sets minimum exchange rate at CHF 1.20 per euro. Comunicazione. 2011a.

http://www.snb.ch/en/mmr/reference/pre_20110906/source/pre_20110906.en.pdf

Banca Nazionale Svizzera (BNS). Monthly statistical bulletin. Dicembre. 2014a.

http://www.snb.ch/ext/stats/statmon/pdf/deen/Stat_Monatsheft.pdf

http://www.snb.ch/ext/stats/statmon/pdf/deen/Stat_Monatsheft.pdf

Corsaro Stefano. I tassi negativi funzionano davvero? L’esempio danese. FinRiskAlert.it. 2014.

https://www.finriskalert.it/?p=1324

Monacelli, Tommaso. Perchè la Svizzera si sgancia dal tasso fisso con l’euro. lavoce.info. 16 gennaio 2015

http://www.lavoce.info/archives/32388/perche-svizzera-si-sgancia-dal-cambio-fisso-leuro/

[1] Per i dati dal 2004 ad oggi, fare riferimento al seguente link: https://oro.bullionvault.it/Prezzo-Oro.do

Further evidence on the Comprehensive Assessment

di Emilio Barucci, Roberto Baviera and Carlo Milani

In our previous column on this site (Barucci, Baviera and Milani, 2015), we reported some evidence on the determinants of capital shortfalls (SF) of the Comprehensive Assessment (CA) performed by the European Central Bank (ECB) and the European Banking Authority (EBA).

In this second column, we focus on four main results.

Core versus non-core euro area countries

The first one, already mentioned in Barucci, Baviera and Milani (2015), refers to the possibility that the ECB and the EBA adopted different approaches with respect to banks depending on their origin country. To address this point, we classify banks/holdings among core countries if they are incorporated in Austria, Belgium, Germany, Finland, France, Luxembourgand the Netherlands (otherwise they are considered among peripheral countries). A different message arises from the AQR and the ST.

With respect to non-performing exposures, in the AQR the effect is positive and significant for peripheral countries, while it is negative and significant for core countries. This outcome can be interpreted in two different ways: either the ECB during CA was benevolent (tough) towards banks incorporated in core (non-core) countries or previously National Competent Authorities of core (non-core) countries adopted a more severe (lighter) control towards domestic banks: in any case we observe a change of pace. Confirming this evaluation, the effect of the coverage ratio in core countries is negative and significant, while in peripheral countries it is not significant. Overall these results suggest that the ECB considered the balance sheets of banks operating in core markets to be cleaner than those of other countries. Finally, the systemic risk associated with a large bank implies a milder impact for banks operating in core countries than for those located in peripheral ones.

Considering the Stress Test (ST) SF, the only difference between the coefficients for core and non-core countries that is significant is the one referring to the systemic risk associated with a bank. This result seems to show that systemic banks operating in core countries are riskier, taking also into account their larger size with respect to the peripheral countries (in average they have a total asset more than two times larger). We may interpret this outcome as an evidence that the ST adverse scenario has not penalized peripheral countries, while the reverse holds true for the AQR.

Role of state aids

The second topic refers to the role of state aids. During the financial crisis, in front of the financial distress of a bank, the states reacted in a very different ways. The European Commission supervises and approves state interventions, but it is difficult to say that the approach was homogeneous as they were mainly approved before strict rules were introduced in 2013. As a matter of fact, state interventions crucially depended on the public finance status of a country (the impact of state aids is estimated to be €250 bln in Germany, €60 bln in Spain, €50 bln in Ireland and the Netherlands, €40 bln in Greece). The debate on the press concentrated on the fact that the CA results may differ because of the amount of state aids in different countries. In particular in some countries (like Italy), it was argued that the financial system did not pass the exam brilliantly because it received a small state support during the crisis. Using different measures of state aids, Barucci, Baviera and Milani (2014) find that state support does not affect the AQR SF. Only direct capital injections have a negative effect on the shortfall. The latter result agrees with the fact that state capital injection increased the CET1 ratio yielding a smaller SF. Instead, the SF of the ST is positively affected by state intervention. This evidence seems to confirm that state aids induced a moral hazard effect with a riskier balance sheet (Dam and Koetter, 2012, Gropp et al., 2010, Mariathasan et al., 2014). However, it is difficult to interpret these results, as they can be the outcome of the deliberate endogenous decision of the bank (moral hazard), or of the state aids pack that often include prescription to the bank to lend money to the private sector.

Regulatory environment

Another point involves the regulatory environment, which may have played a role on the outcome of the AQR and ST exercises. On this issue one can consider four World Bank indicators of the regulatory environment: i) the fraction of banking system’s assets that are under foreign control; ii) an indicator of capital requirement stringency; iii) an indicator of financial conglomerates restrictions; iv) an indicator of the independence of the supervisory authority. The results show that an independent supervisory authority is associated with a smaller AQR SF, instead a stringent capital regulation and restrictions on financial conglomerates lead to a higher SF. The former outcome is expected, instead it is difficult to interpret the latter results, probably at least in part they are related to the fact that with a stringent regulation national discretions did not apply. Results on the ST exercises show that strict rules on capital regulations and restrictions on the activity of financial conglomerates (including shareholding participation in non-financial companies) are associated with a lower SF.

National discretion

One of the main topic in the discussion of the AQR and ST results concerns the role of country specific discretionary measures in the transition to Basel III (Visco, 2014). They are measured, from the capital point of view, considering the difference between the fully loaded CET1 ratio, i.e., the ratio obtained on the basis of the fully applied rules of Basel III, and the CET1 ratio in the transitional period, i.e. based on the national exceptions allowed by CRR/CRD (Capital Requirement Regulation/Directive), as result of the adverse scenario in 2016. Again we observe a different story in the AQR and in the ST.

The analysis shows that national discretion helped to pass the AQR. However, the results show that the ECB has considered banks taking advantage both of national discretions and of an IRB model as more risky, because of the tendency to use the IRB approach in order to reduce the capital absorption in line with the existing literature (see e.g. Beltratti and Paladino, 2013, Mariathasan and Merrouche, 2014, Benh et al., 2014). Moreover, national discretions have a different effect in the AQR depending on the country. The overall negative effect of the national discretion in the AQR is mainly associated with core countries: while in peripheral countries the effect is not significant, the effect is negative and significant for core countries. The average value of the national discretion measures considered, in the two group of countries, is quite similar (33 bps in terms of CET1 ratio for core countries, 36 for the others), and therefore the different effect should not be attributed to the attitude of national supervisors. This result seems to show that the ECB has allowed only the core countries to mitigate the effect of the AQR shortfall thanks to national discretions.

Taking into account the ST SF, different results show up: banks located in countries with a higher freedom to set rules that allow for a smaller capital absorption are also more risky. This outcome is mainly driven by peripheral countries, in opposition to what is observed in the AQR. As a consequence, the national discretions have implied a higher SF in the ST only for banks in countries in bad macroeconomic shape, while banks operating in core countries have not been affected by the possibility to use national discretions.

Conclusions

These results, combined with those of Barucci, Baviera and Milani (2015), shed a grey light on the CA exercise because of some pitfalls in the methodology. The puzzling point is that the AQR and the ST provide so different results.

But is it really strange? How is this fact related to CA ability in capturing banks’ risk?

An answer to these key questions will be provided in a forthcoming column in FinRiskAlert.

References

– Barucci, Emilio, Baviera, Roberto and Milani, Carlo (2014) Is the Comprehensive Assessment really comprehensive?, http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2541043

– Barucci, Emilio, Baviera, Roberto and Milani, Carlo (2015) What are the lessons of the Comprehensive Assessment? A first evidence, FinRiskAlert.it

– Behn, Markus, Haselmann, Rainer and Vig, Vikrant (2014) The limits of model-based regulation, mimeo.

– Beltratti, Andrea and Paladino, Giovanna (2013) Why do banks optimize risk weights? The relevance of the cost of equity capital, mimeo.

– Dam, Lammertjan and Koetter, Michael (2012) Bank bailouts and moral hazard: evidence from Germamy, Review of Financial Studies, 25: 2343-2380.

– Gropp, Reint, Hakenes, Hendrik and Schnabel Isabel (2011) Competition, risk-shifting, and public bail-out policies, Review of Financial Studies, 24: 2084-2120

– Mariathasan, Mike and Merrouche Ourada (2014) The manipulation of Basel risk-weights, Journal of Financial Intermediation, 23: 300-321.

– Mariathasan, Mike, Merrouche, Ouarda and Werger Charlotte (2014) Bailouts and moral hazard: how implicit government Guarantees affect financial stability, mimeo.

– Visco, Ignazio (2014) L’attuazione dell’Unione bancaria europea e il credito all’economia, Audizione del Governatore della Banca d’Italia, Camera dei Deputati, dicembre 2014.

Il Consiglio dell’Unione Europea ha pubblicato un regolamento sui contributi che devono essere versati ex ante al Fondo Unico di Risoluzione (Single Resolution Fund).

La BCE ha approvato l’acquisto di titoli per 60 miliardi di euro al mese, che proseguirà sino alla fine del 2016. L’80% del rischio verrà garantito dalla banche centrali dei paesi di cui si è acquistato il debito. Sono previsti limiti relativamente alle singole emissioni e al debito totale.

Per ulteriori informazioni, leggere qui.

La Banca d’Italia ha pubblicato i risultati dell’indagine sul credito bancario relativa al quarto trimestre 2014.

Indagine sul credito bancario

Nota di commento

Per ulteriori informazioni sul tema, leggere qui.

La Commissione europea ha approvato un regolamento delegato in materia di accesso ed esercizio delle attività di assicurazione e di riassicurazione (Solvency 2). Esso è entrato in vigore il 17 gennaio.

La Commissione europea ha emanato un regolamento sui contributi ex ante ai meccanismi di finanziamento della risoluzione. Esso entrerà in vigore il 6 febbraio.

Seminario presso l’Università di Verona, di seguito il link per la presentazione: