A “stablecoin” is branded anything but, adding to jitters in crypto-markets…

https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2021/02/23/tether-is-fined-by-regulators-in-new-york

A “stablecoin” is branded anything but, adding to jitters in crypto-markets…

https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2021/02/23/tether-is-fined-by-regulators-in-new-york

Most central banks are exploring central bank digital currencies (CBDCs), and their work continues apace amid the Covid-19 pandemic…

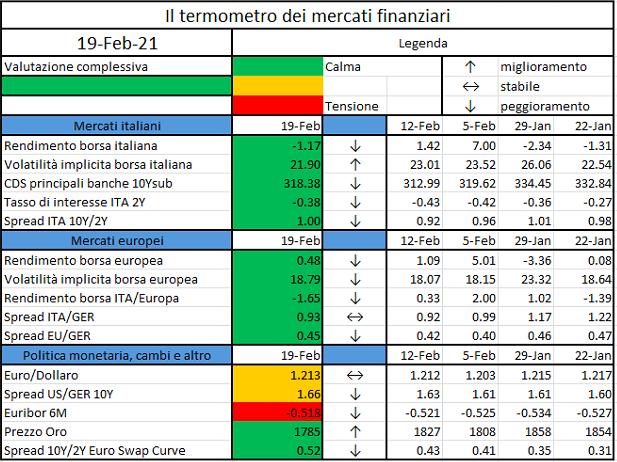

L’iniziativa di Finriskalert.it “Il termometro dei mercati finanziari” vuole presentare un indicatore settimanale sul grado di turbolenza/tensione dei mercati finanziari, con particolare attenzione all’Italia.

Significato degli indicatori

I colori sono assegnati in un’ottica VaR: se il valore riportato è superiore (inferiore) al quantile al 15%, il colore utilizzato è l’arancione. Se il valore riportato è superiore (inferiore) al quantile al 5% il colore utilizzato è il rosso. La banda (verso l’alto o verso il basso) viene selezionata, a seconda dell’indicatore, nella direzione dell’instabilità del mercato. I quantili vengono ricostruiti prendendo la serie storica di un anno di osservazioni: ad esempio, un valore in una casella rossa significa che appartiene al 5% dei valori meno positivi riscontrati nell’ultimo anno. Per le prime tre voci della sezione “Politica Monetaria”, le bande per definire il colore sono simmetriche (valori in positivo e in negativo). I dati riportati provengono dal database Thomson Reuters. Infine, la tendenza mostra la dinamica in atto e viene rappresentata dalle frecce: ↑,↓, ↔ indicano rispettivamente miglioramento, peggioramento, stabilità rispetto alla rilevazione precedente.

Disclaimer: Le informazioni contenute in questa pagina sono esclusivamente a scopo informativo e per uso personale. Le informazioni possono essere modificate da finriskalert.it in qualsiasi momento e senza preavviso. Finriskalert.it non può fornire alcuna garanzia in merito all’affidabilità, completezza, esattezza ed attualità dei dati riportati e, pertanto, non assume alcuna responsabilità per qualsiasi danno legato all’uso, proprio o improprio delle informazioni contenute in questa pagina. I contenuti presenti in questa pagina non devono in alcun modo essere intesi come consigli finanziari, economici, giuridici, fiscali o di altra natura e nessuna decisione d’investimento o qualsiasi altra decisione deve essere presa unicamente sulla base di questi dati.

Last 26th January EIOPA published a methodological paper on the liquidity stress testing for insurances, describing the principles to follow for a good appraisal of the resilience of insurances to liquidity shocks and providing a conceptual approach to measure the liquidity position under adverse scenarios. Indeed, despite the increased interest the NSAs (National Supervisor Authorities) have given to the liquidity risk, a common approach is still missing.

With this paper, EIOPA perseveres with its effort of improving the stress-testing framework, started back in July 2019 and materialized in June 2020, with a consultation paper covering three topics:

Let us discuss the main contents of the 26th January paper, named “Methodological principles of Insurance Stress-testing – liquidity component”.

Objective and scope

The stress testing should have both a micro and macro view, by assessing individual undertakings and by keeping under control the resilience of the entire industry, to avoid a potential spill over to the rest of the economy. The stress test shall be run where the liquidity risk is actually managed, being this the parent company or the local entity.

Definition of Liquidity risk

The liquidity risk describe a situation where an insurance company does not have enough money to pay out the claims. Currently, under the SII framework, the liquidity position is not subject to any quantitative requirement, although even solvent companies can face this risk, being it dependent on the characteristics of assets and liabilities rather than on their size. The liquidity risk for insurance companies has been so far consider of secondary importance, because of the inverted production cycle of the business: the inflow of premiums precedes the outflows of claims, providing a stable source of funding. Nevertheless, specific events can cause unexpected cash outflows that need to be covered.

The banking system considers the liquidity of assets through a haircut on their value: the higher the haircut, the lower the possibility to sell it during a crisis with no or little loss; the time horizon is a key element in determining the haircuts. Cash is considered to be the most liquid asset, with 0% haircut, while, at the opposite side, stand the investment on real estate, even when they cover a short time period.

The liquidity of liabilities is described by the uncertainty around the timing of the payments: the more predictable the cash outflows, the more illiquid the liabilities. In the banking system, this is driven by the volatility of the withdrawals from the deposits; while in the insurance sector, it depends on many factors, including products features, surrender penalties and dynamic policyholder behaviours.

Sources of liquidity risk

On the Asset side we can list

On the Liability side we can list

Measure of liquidity risk

Two perspectives are considered, complementing each other with their pros and cons: the stock-based approach is simpler (for both companies to calculate and regulators to validate), building on existing SII reporting, while the CFs approach provides a more granular view.

Stock-based approach

The Liquidity Stock indicator is defined as a ratio between sources (liquids assets) and needs (liquid liabilities), where original assets and liabilities are changed to consider their liquidity

The Liquid Assets are obtained through the application of the haircuts mentioned above, while Liquid Liabilities can be obtained following two alternative methods:

Cashflow-based approach

Projected liquidity sources (premiums, sales of assets, investment coupons and dividends, reinsurance inflows) and needs (claims, purchase of assets, margin calls, operational expenses, reinsurance outflows) are compared on a given time horizon to determine to what extent outflows are covered by inflows. The CFs should come from real world projections. A CFs indicator can be defined either as a net flow value

or as a ratio between the two.

Stock and flow perspectives can be combined into an integrated indicator of “Sustainability of the flow position”:

In case of negative net flows, the indicator assesses whether Liquid assets are sufficient to cover the outflows.

In case of negative net flows, the indicator assesses whether Liquid assets are sufficient to cover the outflows.

ESMA has published a working paper on MiFID II research unbundling. During the webinar you will see a presentation of the working paper and its findings, followed by a Q&A session…

https://www.esma.europa.eu/press-news/hearings/esma-webinar-wp-mifid-ii-research-unbundling

Severe economic slump with long-lasting effects…

https://www.ecb.europa.eu//press/key/date/2021/html/ecb.sp210218~d8857e8daf.en.pdf

Today I will discuss some recent developments in the foreign exchange market, and provide some views on the role of the Reserve Bank’s various policy measures…

Local firm Bitcoin Suisse has partnered with the canton of Zug, converting cryptocurrency tax payments into Swiss francs…

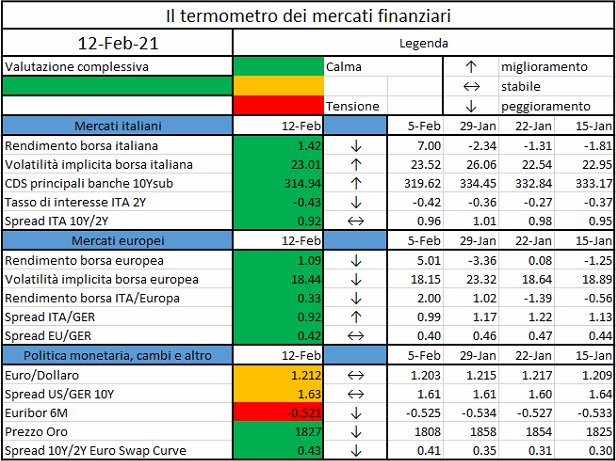

L’iniziativa di Finriskalert.it “Il termometro dei mercati finanziari” vuole presentare un indicatore settimanale sul grado di turbolenza/tensione dei mercati finanziari, con particolare attenzione all’Italia.

Significato degli indicatori

I colori sono assegnati in un’ottica VaR: se il valore riportato è superiore (inferiore) al quantile al 15%, il colore utilizzato è l’arancione. Se il valore riportato è superiore (inferiore) al quantile al 5% il colore utilizzato è il rosso. La banda (verso l’alto o verso il basso) viene selezionata, a seconda dell’indicatore, nella direzione dell’instabilità del mercato. I quantili vengono ricostruiti prendendo la serie storica di un anno di osservazioni: ad esempio, un valore in una casella rossa significa che appartiene al 5% dei valori meno positivi riscontrati nell’ultimo anno. Per le prime tre voci della sezione “Politica Monetaria”, le bande per definire il colore sono simmetriche (valori in positivo e in negativo). I dati riportati provengono dal database Thomson Reuters. Infine, la tendenza mostra la dinamica in atto e viene rappresentata dalle frecce: ↑,↓, ↔ indicano rispettivamente miglioramento, peggioramento, stabilità rispetto alla rilevazione precedente.

Disclaimer: Le informazioni contenute in questa pagina sono esclusivamente a scopo informativo e per uso personale. Le informazioni possono essere modificate da finriskalert.it in qualsiasi momento e senza preavviso. Finriskalert.it non può fornire alcuna garanzia in merito all’affidabilità, completezza, esattezza ed attualità dei dati riportati e, pertanto, non assume alcuna responsabilità per qualsiasi danno legato all’uso, proprio o improprio delle informazioni contenute in questa pagina. I contenuti presenti in questa pagina non devono in alcun modo essere intesi come consigli finanziari, economici, giuridici, fiscali o di altra natura e nessuna decisione d’investimento o qualsiasi altra decisione deve essere presa unicamente sulla base di questi dati.

Discussing the role of banks in the time of COVID-19 is indeed vital. Banking is as important to the economy as the heart is to the human body…