The head of the world’s largest asset manager has provided a somewhat bullish take on the world’s first cryptocurrency…

The effects of the Covid crisis have been felt unevenly across sectors, and the output of customer service industries could remain well below its pre-Covid trend for some time…

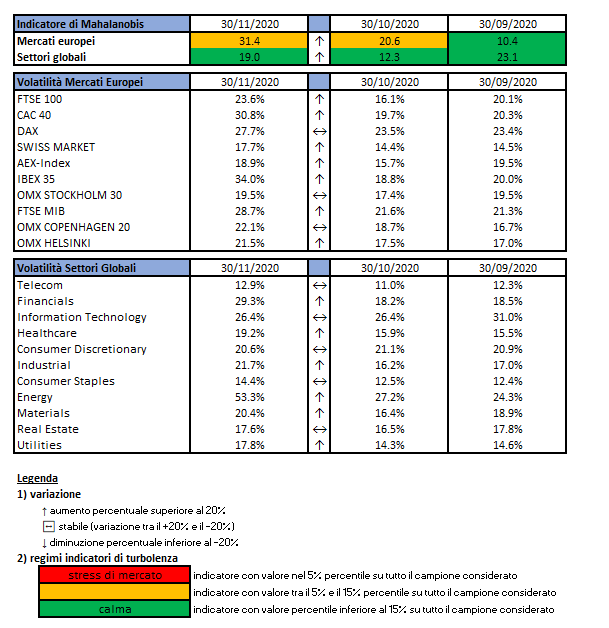

L’indicatore di Mahalanobis permette di evidenziare periodi di stress nei mercati finanziari. Si tratta di un indicatore che dipende dalle volatilità e dalle correlazioni di un particolare universo investimenti preso ad esame. Nello specifico ci siamo occupati dei mercati azionari europei e dei settori azionari globali.

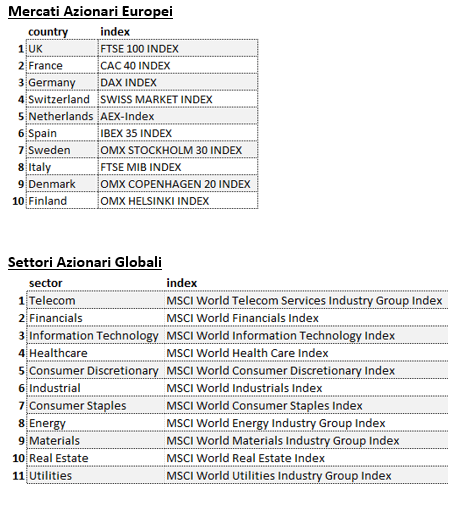

Gli indici utilizzati sono:

Le volatilità riportate sono storiche e calcolate sugli ultimi 30 trading days disponibili. Per ogni asset-class dunque sono prima calcolati i rendimenti logaritmici dei prezzi degli indici di riferimento, successivamente si procede col calcolo della deviazione standard dei rendimenti, ed infine si procede a moltiplicare la deviazione standard per il fattore di annualizzazione.

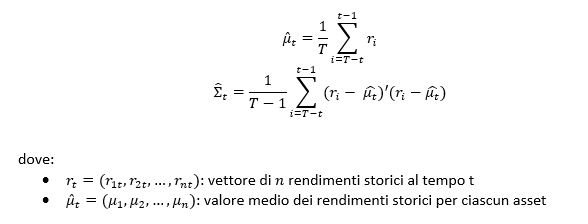

Per il calcolo della distanza di Mahalnobis si procede dapprima con la stima della matrice di covarianza tra le asset-class. Si considera l’approccio delle finestre mobili. Come con la volatilità, si procede prima con il calcolo dei rendimenti logaritmici e poi con la stima storica della matrice di covarianza, come riportato di seguito.

Supponendo una finestra mobile di T periodi, viene calcolato il valore medio e la matrice varianza covarianza al tempo t come segue:

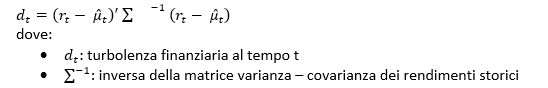

La distanza di Mahalanobis è definita formalmente come:

Le parametrizzazioni che sono state scelte sono:

- Rilevazioni mensili

- Tempo T della finestra mobile pari a 5 anni (60 osservazioni mensili)

Le statistiche percentili sono state calcolate a partire dalla distribuzione dell’indicatore di Mahalanobis dal Dicembre 1997 al Dicembre 2019 su rilevazioni mensili.

Ulteriori dettagli sono riportati in questo articolo.

Disclaimer: Le informazioni contenute in questa pagina sono esclusivamente a scopo informativo e per uso personale. Le informazioni possono essere modificate da finriskalert.it in qualsiasi momento e senza preavviso. Finriskalert.it non può fornire alcuna garanzia in merito all’affidabilità, completezza, esattezza ed attualità dei dati riportati e, pertanto, non assume alcuna responsabilità per qualsiasi danno legato all’uso, proprio o improprio delle informazioni contenute in questa pagina. I contenuti presenti in questa pagina non devono in alcun modo essere intesi come consigli finanziari, economici, giuridici, fiscali o di altra natura e nessuna decisione d’investimento o qualsiasi altra decisione deve essere presa unicamente sulla base di questi dati.

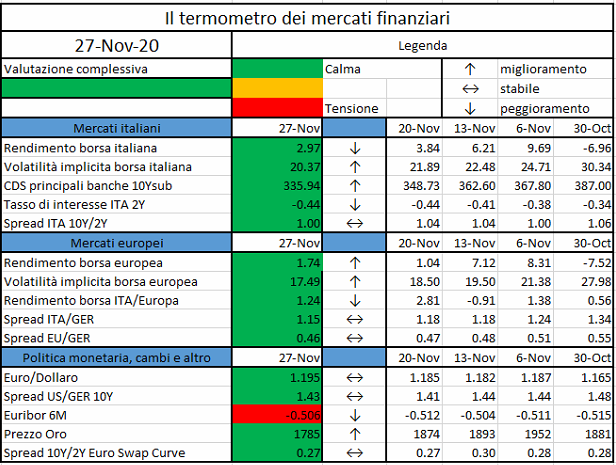

Il termometro dei mercati finanziari (27 Novembre 2020)

a cura di Emilio Barucci e Daniele Marazzina

L’iniziativa di Finriskalert.it “Il termometro dei mercati finanziari” vuole presentare un indicatore settimanale sul grado di turbolenza/tensione dei mercati finanziari, con particolare attenzione all’Italia.

Significato degli indicatori

- Rendimento borsa italiana: rendimento settimanale dell’indice della borsa italiana FTSEMIB;

- Volatilità implicita borsa italiana: volatilità implicita calcolata considerando le opzioni at-the-money sul FTSEMIB a 3 mesi;

- Future borsa italiana: valore del future sul FTSEMIB;

- CDS principali banche 10Ysub: CDS medio delle obbligazioni subordinate a 10 anni delle principali banche italiane (Unicredit, Intesa San Paolo, MPS, Banco BPM);

- Tasso di interesse ITA 2Y: tasso di interesse costruito sulla curva dei BTP con scadenza a due anni;

- Spread ITA 10Y/2Y : differenza del tasso di interesse dei BTP a 10 anni e a 2 anni;

- Rendimento borsa europea: rendimento settimanale dell’indice delle borse europee Eurostoxx;

- Volatilità implicita borsa europea: volatilità implicita calcolata sulle opzioni at-the-money sull’indice Eurostoxx a scadenza 3 mesi;

- Rendimento borsa ITA/Europa: differenza tra il rendimento settimanale della borsa italiana e quello delle borse europee, calcolato sugli indici FTSEMIB e Eurostoxx;

- Spread ITA/GER: differenza tra i tassi di interesse italiani e tedeschi a 10 anni;

- Spread EU/GER: differenza media tra i tassi di interesse dei principali paesi europei (Francia, Belgio, Spagna, Italia, Olanda) e quelli tedeschi a 10 anni;

- Euro/dollaro: tasso di cambio euro/dollaro;

- Spread US/GER 10Y: spread tra i tassi di interesse degli Stati Uniti e quelli tedeschi con scadenza 10 anni;

- Prezzo Oro: quotazione dell’oro (in USD)

- Spread 10Y/2Y Euro Swap Curve: differenza del tasso della curva EURO ZONE IRS 3M a 10Y e 2Y;

- Euribor 6M: tasso euribor a 6 mesi.

I colori sono assegnati in un’ottica VaR: se il valore riportato è superiore (inferiore) al quantile al 15%, il colore utilizzato è l’arancione. Se il valore riportato è superiore (inferiore) al quantile al 5% il colore utilizzato è il rosso. La banda (verso l’alto o verso il basso) viene selezionata, a seconda dell’indicatore, nella direzione dell’instabilità del mercato. I quantili vengono ricostruiti prendendo la serie storica di un anno di osservazioni: ad esempio, un valore in una casella rossa significa che appartiene al 5% dei valori meno positivi riscontrati nell’ultimo anno. Per le prime tre voci della sezione “Politica Monetaria”, le bande per definire il colore sono simmetriche (valori in positivo e in negativo). I dati riportati provengono dal database Thomson Reuters. Infine, la tendenza mostra la dinamica in atto e viene rappresentata dalle frecce: ↑,↓, ↔ indicano rispettivamente miglioramento, peggioramento, stabilità rispetto alla rilevazione precedente.

Disclaimer: Le informazioni contenute in questa pagina sono esclusivamente a scopo informativo e per uso personale. Le informazioni possono essere modificate da finriskalert.it in qualsiasi momento e senza preavviso. Finriskalert.it non può fornire alcuna garanzia in merito all’affidabilità, completezza, esattezza ed attualità dei dati riportati e, pertanto, non assume alcuna responsabilità per qualsiasi danno legato all’uso, proprio o improprio delle informazioni contenute in questa pagina. I contenuti presenti in questa pagina non devono in alcun modo essere intesi come consigli finanziari, economici, giuridici, fiscali o di altra natura e nessuna decisione d’investimento o qualsiasi altra decisione deve essere presa unicamente sulla base di questi dati.

Earlier this month, reacting to a decision by India’s highest court, prominent comedian Kunal Kamra tweeted that India’s Supreme Court is the “most Supreme joke of this country.”…

Dispersed economic and financial market impact on countries and sectors could lead to concentration of risks in some areas…

https://www.ecb.europa.eu//press/pr/date/2020/html/ecb.pr201125~01dfca322a.en.html

The emergence of distributed ledger technology (DLT) and rapid advances in traditional centralised systems are moving the technological horizon of money and payments…

The European Banking Authority (EBA), the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions

Authority (EIOPA …

https://www.esma.europa.eu/file/69147/download?token=4Lolju50

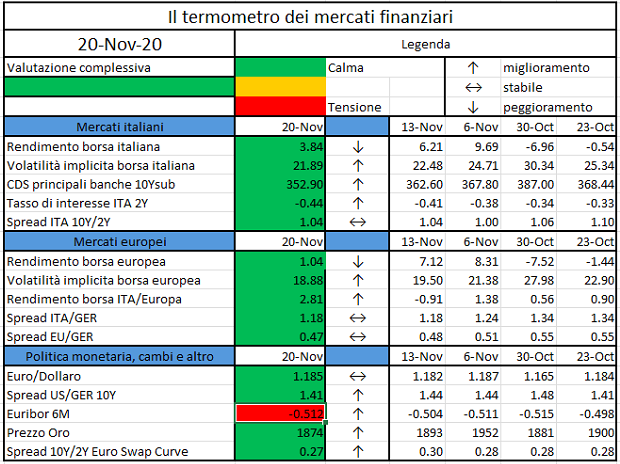

Il termometro dei mercati finanziari (20 Novembre 2020)

a cura di Emilio Barucci e Daniele Marazzina

L’iniziativa di Finriskalert.it “Il termometro dei mercati finanziari” vuole presentare un indicatore settimanale sul grado di turbolenza/tensione dei mercati finanziari, con particolare attenzione all’Italia.

Significato degli indicatori

- Rendimento borsa italiana: rendimento settimanale dell’indice della borsa italiana FTSEMIB;

- Volatilità implicita borsa italiana: volatilità implicita calcolata considerando le opzioni at-the-money sul FTSEMIB a 3 mesi;

- Future borsa italiana: valore del future sul FTSEMIB;

- CDS principali banche 10Ysub: CDS medio delle obbligazioni subordinate a 10 anni delle principali banche italiane (Unicredit, Intesa San Paolo, MPS, Banco BPM);

- Tasso di interesse ITA 2Y: tasso di interesse costruito sulla curva dei BTP con scadenza a due anni;

- Spread ITA 10Y/2Y : differenza del tasso di interesse dei BTP a 10 anni e a 2 anni;

- Rendimento borsa europea: rendimento settimanale dell’indice delle borse europee Eurostoxx;

- Volatilità implicita borsa europea: volatilità implicita calcolata sulle opzioni at-the-money sull’indice Eurostoxx a scadenza 3 mesi;

- Rendimento borsa ITA/Europa: differenza tra il rendimento settimanale della borsa italiana e quello delle borse europee, calcolato sugli indici FTSEMIB e Eurostoxx;

- Spread ITA/GER: differenza tra i tassi di interesse italiani e tedeschi a 10 anni;

- Spread EU/GER: differenza media tra i tassi di interesse dei principali paesi europei (Francia, Belgio, Spagna, Italia, Olanda) e quelli tedeschi a 10 anni;

- Euro/dollaro: tasso di cambio euro/dollaro;

- Spread US/GER 10Y: spread tra i tassi di interesse degli Stati Uniti e quelli tedeschi con scadenza 10 anni;

- Prezzo Oro: quotazione dell’oro (in USD)

- Spread 10Y/2Y Euro Swap Curve: differenza del tasso della curva EURO ZONE IRS 3M a 10Y e 2Y;

- Euribor 6M: tasso euribor a 6 mesi.

I colori sono assegnati in un’ottica VaR: se il valore riportato è superiore (inferiore) al quantile al 15%, il colore utilizzato è l’arancione. Se il valore riportato è superiore (inferiore) al quantile al 5% il colore utilizzato è il rosso. La banda (verso l’alto o verso il basso) viene selezionata, a seconda dell’indicatore, nella direzione dell’instabilità del mercato. I quantili vengono ricostruiti prendendo la serie storica di un anno di osservazioni: ad esempio, un valore in una casella rossa significa che appartiene al 5% dei valori meno positivi riscontrati nell’ultimo anno. Per le prime tre voci della sezione “Politica Monetaria”, le bande per definire il colore sono simmetriche (valori in positivo e in negativo). I dati riportati provengono dal database Thomson Reuters. Infine, la tendenza mostra la dinamica in atto e viene rappresentata dalle frecce: ↑,↓, ↔ indicano rispettivamente miglioramento, peggioramento, stabilità rispetto alla rilevazione precedente.

Disclaimer: Le informazioni contenute in questa pagina sono esclusivamente a scopo informativo e per uso personale. Le informazioni possono essere modificate da finriskalert.it in qualsiasi momento e senza preavviso. Finriskalert.it non può fornire alcuna garanzia in merito all’affidabilità, completezza, esattezza ed attualità dei dati riportati e, pertanto, non assume alcuna responsabilità per qualsiasi danno legato all’uso, proprio o improprio delle informazioni contenute in questa pagina. I contenuti presenti in questa pagina non devono in alcun modo essere intesi come consigli finanziari, economici, giuridici, fiscali o di altra natura e nessuna decisione d’investimento o qualsiasi altra decisione deve essere presa unicamente sulla base di questi dati.

Last July EIOPA submitted its response to the consultation the European Commission (EC) had launched regarding the sustainable finance, whose aim is promoting a sustainable financial environment by increasing private investment in sustainable projects. Here are the main outcomes:

- EIOPA supports the EU proposal of a free and publicly accessible database containing ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) information of corporates and financial institutions, while opposes to sharing confidential supervisory reporting data

- EIOPA supports the development of a European wide ESG benchmark, with objective and measurable criteria for the inclusion or the exclusion of assets

- EIOPA believes that financial institutions should provide an estimate on how their portfolios are in line with the goals of the Paris agreement (see below) by computing the increase in temperature (e.g. 2°C, 3°C, 4°C) related to the investments they are financing. The methodology to carry out the calculations is still to define and should help in preventing the practice of green washing (institutions appear to spend more money on advertising to be “green”, than on finding environmental-friendly practices)

- EIOPA supports the inclusion of variable remuneration for executive officers linked to non-financial performance, while opposes the introduction of a mandatory minimum share

- EIOPA agrees that insurance and pension funds should foster the environmental and social sustainability, having at disposal sustainability data and a robust and proportionate regulatory framework.

Let us take a step back, to see where all of this began.

Everything started back to September 2015, when the leaders of 193 countries stated a list of 17 sustainable development goals, to be reached by 2030, the so-called “Agenda 2030”. The goals attained a wide range of topics, among which fighting hunger, reducing economic inequalities and promoting sustainable models of production and consumption. The unsustainability of the development model was explicitly recognized for the first time.

Three months later, on December 2015, 195 countries signed the Paris agreement, committing to determine, plan, and report on their contribution to mitigate global warming. The increase in temperature should stay well below 2°C, where 0°C is pre-industrial level.

To help to make this happen, in March 2018, the EC published its Action Plan on sustainable finance, aiming at reorienting the capital flows of the private sector towards sustainable investments. Other targets of the Action Plan were to take into proper consideration the risks stemming from climate change and to promote transparency and long-termism in the financial and economic activities of the private sector.

Later or, in August 2018, the EC asked EIOPA to which extent sustainability was considered within the SII framework. EIOPA pointed out that medium to long term impacts of climate change were not fully captured in the SII capital requirements of Pillar I, being those designed to reflect the risk over just a 1 year time horizon. Another point EIOPA made was the need of a commonly agreed “taxonomy” regarding what is sustainable and what is not (https://www.finriskalert.it/climate-change-and-sii-a-cura-di-di-silvia-dellacqua).

In June 2019, the EBA (European Banking Authority) launched a consultation among the financial institutions, which resulted in the “Guidelines on loan origination and monitoring”, where it is advised to consider ESG factors in the internal policies used to grant loans and in the credit risk management practices.

Afterwards, in December 2019, Ursula von der Leyen, president of the EC, presented the “European Green Deal”: a roadmap to make all member states carbon neutral by 2050, while reducing pollution and creating job opportunities by the development of a new economy.

Later on, in March 2020, the EC published the “EU taxonomy for sustainable activities”: a technical report to help investors assessing whether or not investments meet robust environmental standards and are compliant to the Paris agreement.

This brings us to the current situation: last April 2020 the three European supervisory authorities published a joint Consultation Paper on ESG Disclosures containing proposals of common reporting standards on the sustainability of investment products, which would allow financial consultants to take an informed choice on the main positive or adverse impacts their investments can have. EIOPA submitted its response last July 2020.