The European Securities and Market Authority (ESMA) issued the first report on the supervisory measures and penalties carried out under the European Market Infrastructure Regulation (EMIR). The report focuses in particular on the supervisory actions undertaken national authorities, their supervisory powers and the interaction between these authorities and market participants when monitoring the compliance of the following EMIR requirements:

- the clearing obligation for certain OTC derivatives (Art. 4 EMIR);

- the reporting obligation of derivative transactions to TRs (Art. 9 EMIR);

- requirements for non-financial counterparties (Art. 10 EMIR); and

- Risk mitigation techniques for non-cleared OTC derivatives (Art. 11 EMIR).

ESMA has sent its report to the European Parliament, the Council and the Commission today, informing them about the findings, which will also help to gradually identifying best practices and potential areas that could benefit from a higher level of harmonisation.

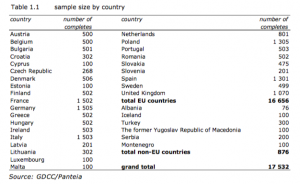

Regarding the organization and allocation of competences related to the provisions in Articles 4, 9, 10 and 11 of EMIR, 14 countries (AT, CZ, DK, DE, FI, HU, IE, LV, MT, NO, PL, ES, SE, SK) have the supervisory powers and the power to impose penalties centralised in one single National Competent Authorities (NCA). It is observed that, among the countries with a single authority in charge of the supervision and the imposition of penalties, in 5 (AT, DK, FI, LV, SK.) out of 14, both the supervisory actions and the imposition of penalties are taken care by the same team/unit within the single authority.

On the contrary, the other 9 out of the 14 countries with a single authority there is a clear separation between the teams involved. In some NCAs, such as in the case of Germany and Ireland, the supervisory function is also split depending on the type of counterparty or on the specific provisions that are being monitored.

In respect to the other twelve countries (out of 26) that have the supervisory powers and the power to impose penalties decentralised and split between different NCAs, we observe that the majority of them share these competences with their respective Central Banks (with the exception of LX, IT, PT, SJ and SK).

In IE, sectoral supervision teams are responsible for supervising different entities’ compliance with all applicable legislation (including EMIR). The team responsible for supervising funds is also responsible for monitoring non-financial counterparties. In DE, one team focuses on matters related to Arts. 4, 10-11 and the other, to art. 9 of EMIR. In Italy, besides the role of BdI, Covip and IVASS are responsible respectively for the regulatory surveillance of pension funds and insurances.

The data gathered from the survey sheds some light on the level of interaction and the means used by the authorities to interact with market participants in relation to the implementation or the phase-in of EMIR provisions (in particular, Articles 4, 9 and 11 of EMIR).

The authorities have engaged in different activities aimed at providing awareness, training and guidance. In the majority of the 26 countries, authorities have engaged directly with market participants through different initiatives. Around 54% have launched processes to get feedback during the process of the EMIR implementation, with similar figures in respect to the clearing and the risk mitigation techniques and a higher percentage with respect to the reporting obligation. Around 58% of the NCAs have prepared specific trainings. In addition, 35% of the NCAs have engaged in working groups with market participants’ representatives.

Regarding the clearing obligation (Article 4 of EMIR), in Austria, Germany and Italy, authorities held trainings on intragroup transactions exemptions and the corresponding notifications. In Malta, three training sessions were organised for market participants (one with the participation of ESMA staff), focused on the clearing obligation, the intragroup exemptions regime and clearing obligation as applicable to financial and non-financial counterparties. In some countries, such as Belgium , trainings were addressed to independent auditors, who under the national law are responsible for checking the compliance of some entities with the provisions in Articles 4, 9 and 10 of EMIR. Another method used by some NCAs to interact with market participants is to establish working groups with representatives of market participants. In total, around 35% of the NCAs set up working groups in relation to Articles 4, 9 and 11 of EMIR44.

The report serves as a good basis for NCAs to share on their practices in their supervisory activities and more broadly, to raise awareness on the supervisory approaches followed in the different countries. It helps understand the information checked by NCAs and its use, for a range of supervisory measures.

The report also shows that the majority of NCAs share similar competences in their supervision and enforcement of Articles 4, 9, 10 and 11 of EMIR. ESMA expects this first report to be the baseline for future reports on penalties and supervisory measures, which will help monitor compliance in the different member states and possibly identify areas where a higher level of harmonisation could be considered to ensure a level playing field.

Supervisory Measures and Penalties under Articles 4, 9, 10 and 11 of EMIR (PDF)