By allowing banks to run down some of their buffers, policymakers are sending a strong signal…

The COVID-19 pandemic has severely disrupted the global economy at every level…

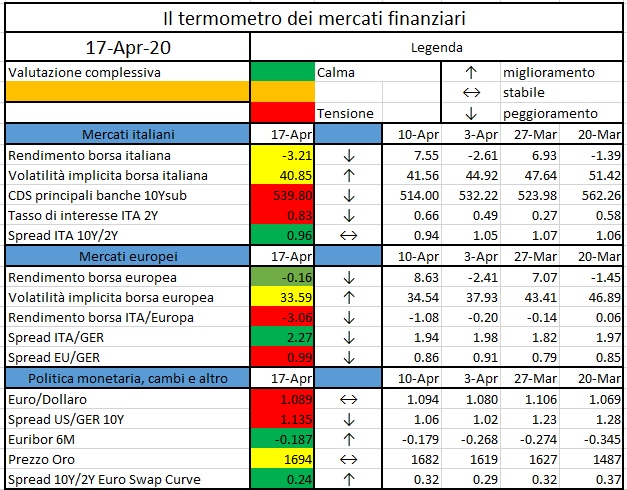

L’iniziativa di Finriskalert.it “Il termometro dei mercati finanziari” vuole presentare un indicatore settimanale sul grado di turbolenza/tensione dei mercati finanziari, con particolare attenzione all’Italia.

Significato degli indicatori

- Rendimento borsa italiana: rendimento settimanale dell’indice della borsa italiana FTSEMIB;

- Volatilità implicita borsa italiana: volatilità implicita calcolata considerando le opzioni at-the-money sul FTSEMIB a 3 mesi;

- Future borsa italiana: valore del future sul FTSEMIB;

- CDS principali banche 10Ysub: CDS medio delle obbligazioni subordinate a 10 anni delle principali banche italiane (Unicredit, Intesa San Paolo, MPS, Banco BPM);

- Tasso di interesse ITA 2Y: tasso di interesse costruito sulla curva dei BTP con scadenza a due anni;

- Spread ITA 10Y/2Y : differenza del tasso di interesse dei BTP a 10 anni e a 2 anni;

- Rendimento borsa europea: rendimento settimanale dell’indice delle borse europee Eurostoxx;

- Volatilità implicita borsa europea: volatilità implicita calcolata sulle opzioni at-the-money sull’indice Eurostoxx a scadenza 3 mesi;

- Rendimento borsa ITA/Europa: differenza tra il rendimento settimanale della borsa italiana e quello delle borse europee, calcolato sugli indici FTSEMIB e Eurostoxx;

- Spread ITA/GER: differenza tra i tassi di interesse italiani e tedeschi a 10 anni;

- Spread EU/GER: differenza media tra i tassi di interesse dei principali paesi europei (Francia, Belgio, Spagna, Italia, Olanda) e quelli tedeschi a 10 anni;

- Euro/dollaro: tasso di cambio euro/dollaro;

- Spread US/GER 10Y: spread tra i tassi di interesse degli Stati Uniti e quelli tedeschi con scadenza 10 anni;

- Prezzo Oro: quotazione dell’oro (in USD)

- Spread 10Y/2Y Euro Swap Curve: differenza del tasso della curva EURO ZONE IRS 3M a 10Y e 2Y;

- Euribor 6M: tasso euribor a 6 mesi.

I colori sono assegnati in un’ottica VaR: se il valore riportato è superiore (inferiore) al quantile al 15%, il colore utilizzato è l’arancione. Se il valore riportato è superiore (inferiore) al quantile al 5% il colore utilizzato è il rosso. La banda (verso l’alto o verso il basso) viene selezionata, a seconda dell’indicatore, nella direzione dell’instabilità del mercato. I quantili vengono ricostruiti prendendo la serie storica di un anno di osservazioni: ad esempio, un valore in una casella rossa significa che appartiene al 5% dei valori meno positivi riscontrati nell’ultimo anno. Per le prime tre voci della sezione “Politica Monetaria”, le bande per definire il colore sono simmetriche (valori in positivo e in negativo). I dati riportati provengono dal database Thomson Reuters. Infine, la tendenza mostra la dinamica in atto e viene rappresentata dalle frecce: ↑,↓, ↔ indicano rispettivamente miglioramento, peggioramento, stabilità rispetto alla rilevazione precedente.

Disclaimer: Le informazioni contenute in questa pagina sono esclusivamente a scopo informativo e per uso personale. Le informazioni possono essere modificate da finriskalert.it in qualsiasi momento e senza preavviso. Finriskalert.it non può fornire alcuna garanzia in merito all’affidabilità, completezza, esattezza ed attualità dei dati riportati e, pertanto, non assume alcuna responsabilità per qualsiasi danno legato all’uso, proprio o improprio delle informazioni contenute in questa pagina. I contenuti presenti in questa pagina non devono in alcun modo essere intesi come consigli finanziari, economici, giuridici, fiscali o di altra natura e nessuna decisione d’investimento o qualsiasi altra decisione deve essere presa unicamente sulla base di questi dati.

The “Great Lockdown” is redrawing the bitcoin mining landscape as the economic crisis makes smaller operations less profitable and access to China’s hardware supply chains crucial…

The COVID-19 pandemic is a shock of unprecedented intensity and severity. The challenges facing all parts of the economy in dealing with the economic, humanitarian and social consequences of this crisis are historic…

https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2020/html/ecb.sp200416~4d6bd9b9c0.en.html

The European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), the EU’s securities markets regulator, has issued opinions agreeing to the renewal of the emergency restrictions on short selling…

Financial technology can spur financial inclusion by facilitating payments, but the opportunities come with challenges…

A partire dai noti problemi di manipolazione dei tassi LIBOR, su spinta del Financial Stability Board è stata condotta a livello internazionale una ampia riforma per la messa a punto di nuovi tassi benchmark. In questo lavoro primo di una serie dopo una breve review cerchiamo di focalizzare le modifiche operative sul mercato dei tassi, determinate dalle scelte compiute.

1 La genesi della crisi. Importanza e fragilità dei tassi IBOR

A partire dai primi anni post-crisi Lehman del 2008 si sono susseguite notizie sul tema della manipolazione dei tassi LIBOR (ed EURIBOR) a partire proprio dagli anni della crisi, che poi nei casi comprovati hanno avuto lunghe indagini con conseguenze penali. Come noto, lo scandalo ha toccato alcune delle principali banche internazionali come Barclays e lambito anche istituzioni come la Bank of England.

Non ci interessa però seguire o rappresentare l’intricato percorso investigativo degno di una spy story. Tra le tante, una avvincente ricostruzione di un tassello del mosaico si trova in [4].

Ci limitiamo a sintetizzare perché tali tassi siano importanti e perché fossero essenzialmente fragili.

Innanzitutto, è necessaria un po’ di chiarezza terminologica. Se LIBOR è acronimo di “London InterBank Offered Rate”, va intanto chiarito che non era e non è riferito solo ai tassi di interesse per prestiti espressi in GBP, ma è quotato per numerose currency, tra cui GBP, USD, EUR, tanto che si parla di “GBP LIBOR”, “USD LIBOR”, “CFH LIBOR”, ecc. Con “IBOR” si intende pertanto la pluralità dei tassi quotati secondo un frameword di regole comuni. Esiste quindi anche lo “EUR LIBOR”, da non confondere con EURIBOR.

Perché così importanti questi tassi, detti reference rate? Perché a livello internazionale e locale, la gran parte dei prodotti del mercato bancario e finanziario sono indicizzati a questi tassi.

In concreto, gli interessi pagati sui mutui, sui prestiti obbligazionari a tasso variabile, sui conti correnti come sugli anticipi del portafoglio commerciale, sono pressoché sempre determinati e rinegoziati in base alle variazioni periodiche di questi tassi. Come noto, caso per caso viene poi aggiunto uno spread in base al merito di credito della controparte e alla forza contrattuale tra le parti. Infine anche molti prodotti come i fondi comuni hanno un benchmark di riferimento o un rendimento target costituito da questi tassi di interesse.

I tassi LIBOR sono quotati su alcune scadenza standard, cioè: 1D,1W,1M,2M,3M,6M,12M.

Al tempo stesso, poiché la funzione principale dei derivati è quella offrire hedging sul rischio, tra cui il rischio di tasso, la gran parte dei derivati in qeustione, come Irs, Cap e Floor, è riferita a questi tassi.

Perché si è innescata la crisi di credibilità di questi tassi e le relative riforme?

Sostanzialmente perché i valori ufficiali del LIBOR sono quote-driven, non transaction based.

I valori ufficiali del LIBOR, il cosiddetto fixing, pubblicati alle 11 del mattino da Reuters, sono determinati da un panel di alcune banche, variabili in base alla currency, ma comunque in numero limitato, inferiore a 20 (19 per EURIBOR).

La pubblicazione, tanto per i LIBOR quanto per il “vecchio EURIBOR” si basa su metodo di media con taglio delle code. Cioè vengono eliminati i valori estremi della contribuzione, con diverse regole tra caso e caso, e se ne calcola la media.

Perché fragilità? In primis un metodo basato su quotazioni di un panel non riflette le effettive operazioni di prestito sul mercato. Ricordiamo che la crisi del 2008 è statr anche e soprattutto una crisi di liquidità, e ha portato a una generale rarefazione del mercato interbancario unsecured, quello in cui i prestiti non sono assistiti da collatateral.

Soprattutto, se un contributore vuole influenzare una contribuzione a proprio favore, è sufficiente anche l’accordo con pochi altri per variazioni significative.

ESEMPIO: panel di 7 banche, calcolo su media con esclusione dei due estremi. Per una manipolazione verso l’alto, basta l’accordo di due contributori che pubblicano quote molto elevate per avere un impatto, in quanto solo il valore più alto viene escluso.

Le banche come noto rivalutano secondo il princpio del mark to market (MtM) il loro portafoglio di trading con frequenza quotidiana, e con la sensitivity misurano la sensibilità del valore del portafgolio a variazioni di tasso. La grandezza BPV, basis point value, indica di quanto cambia il mark to market, quindi il conto economico giornaliero, al variare di un basis point cioè 0.01%.

Banche di dimensioni rilevanti hanno portafogli con BPV dell’ordine dei miliomi di euro, quindi si intuiscono gli immensi conflitti di interesse legati a una possibile manipolazione, anche infinitesima, dei market data in input al processo di pricing.

Tutto questo ha portato a un lungo processo di riforma, ispirato alle linee guida emesse dal Financial Stability Board, si veda [1].

2 Pilastri della riforma dei tassi benchmark. Il tasso €STR

La riforma dei tassi benchmark è stato ed è tuttora un processo che per ampiezza, complessità, impatti sui processi bancari e sulla clientela non ha eguali, superiore anche alla più famosa riforma di Basilea sul capitale. Come detto, la spinta parte dalle guidelines di FSB, e per l’Unione Europea ha attuazione nella cosiddetta BMR, benchmark regulation, si veda [9]. L’attuazione della riforma coinvolge numerosi gruppi di lavoro che vedono al tavolo, in genere per ogni currency, regulator, istituzioni di categoria, rappresentanti di banche di grande dimensione.

Questi i principi essenziali della riforma:

- i tassi benchmark sono suddivisi in critici (come Euribor ed Eonia), significativi e non critici

- specie per i tassi critici, sono stabiliti processi molto severi di governo, controllo, trasparenza

- sono definiti gli enti responsabili di questo processo di pubblicazione, in Europa BCE per tasso Eonia (il tasso overnight usato molto in prodotti quali gli IRS detti OIS) ed EMMI (European Money Market Institute) per Euribor

- sono pure catalogati i benchmark administrators, cioè provider di mercato (Bloomberg, Reuters, ICE, CME, ecc) che possono pubblicare i fixing di tali tassi e grandezze da questi ricavate. Per Unione Europea tali adminstrators sono autorizzati mediante apposito registro da ESMA

- per i nuovi tassi benchmark prevale la logica di un valore transaction based, basato su operazioni effettive tra banche, in alcuni casi anche con large corporate, essendo la liquidità e quindi la credibilità il primo obiettivo della riforma

- A livello globale, di conseguenza anche a livello contrattuale nei rapporti con la clientela, deve essere definito un fallback, cioè un tasso sostitutivo da applicare nel caso il benchmark di riferimento non sia più disponibile, temporaneamente o in modo definitivo.

In riferimento alla riforma, da osservare che per il mercato overnight in europa il tasso €STR (Ester) dal 2 ottobre 2019 ha soppiantato il tasso EONIA.

Questo ovviamente ha posto vari problemi di migrazione o gestione per tutti i contratti, specie derivati, in essere a quella data. Da una analisi parallela su opportune serie storiche si è osservato che la differenza media tra i due tassi era di 0.085%. Da tale data quindi i contratti riferiti a Eonia vengano gestiti, a livello di calcolo cedole, ratei, liquidazioni, utilizzando per convenzione (di fatto un primo importante esempio di fall back) il valore

EONIA_FALLBACK = €STR – 0.085%

Allo stesso modo per EURIBOR è stata definita e validata la nuova metodologia del cosiddetto Euribor Ibrido, che in base a una sequenza di regole privilegia il dato riveniente da operazioni effettive rispetto a quello delle quotazioni o di panel.

Da ricordare infine che il 22 giugno 2020 London Clearing House (LCH), la principale clearing house europea, provederà al discounting switch, cioè al passaggio dal tasso Eonia al tasso €STR per la costruzione della curva di discounting, essenziale per il calcolo del MtM e di conseguenza per il calcolo dei margini di variazione giornalieri.

3 I nuovi tassi benchmark. Prime tappe della riforma. La rivoluzione dei tassi overnight

Veniamo ora ad alcuni aspetti operativi di mercato dei nuovi tassi benchmark, che oltretutto hanno lo scopo di fungere da migliore possibile versione di mercato del tasso free-risk, parametro chiave di tutti i processi di valutazione del valore e del rischio.

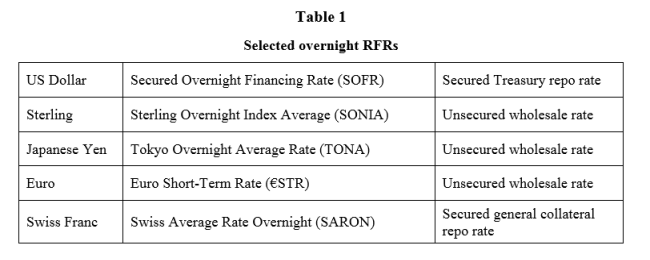

Come detto, vari gruppi di lavoro per le diverse aree valutarie hanno scelto per ogni currency i tassi di riferimento, qui sotto una tabella, ripresa da [2] e [3], sui quali si trovano molti elementi utili.

Alcune prime considerazioni.

- Si tratta per tutti i mercati di tassi Overnight

- Alcuni di essi sono secured, come il tasso americano SOFR e il SARON svizzero, altri unsecured. Questo perché hanno prevalso tassi provenienti da mercati molto liquidi, e per esempio per gli Stati Uniti il mercato dei pronti termine (tipica operazione di lending secured) è iper liquido

- In questo dominio di tassi overnight, il caso dell’Euro è l’unico rilevante in cui oltre a un benchmark rate overnight, rimane in vigore un tasso a termine tradizionale, cioè Euribor (ibrido) sulle diverse scadenze.

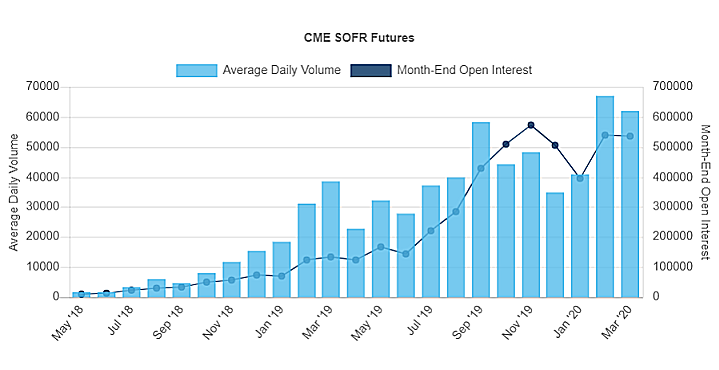

Vediamo di seguito i volumi delle operazioni in derivati quotati sul SOFR presso il mercato CME (dati in mln $). Volumi ancora inferiori rispetto al tradizionale mercato dei derivati su USD Libor ma già molto significativi.

Vediamo di seguito i volumi delle operazioni in derivati quotati sul SOFR presso il mercato CME (dati in mln $). Volumi ancora inferiori rispetto al tradizionale mercato dei derivati su USD Libor ma già molto significativi.

Ma quale è il vero punto che possiamo definire rivoluzionario di questa riforma?

Alla base di tuti i processi di valutazione in finanza si pone la curva dei tassi (yield curve), cioè la curva zero coupon che permette di determinare il valore attuale dei flussi futuri e quindi step essenziale di tutti i processi di pricing. Oltre alla curva di sconto, altrettanto importanti le curve forward per determinare i flussi futuri attesi per i prodotti floating rate.

Tale curva è ottenuta con il processo di bootstrap dai market data, cioè dalle quotazioni osservabili sul mercato.

E per la parte breve della curva i term rate sono l’input fondamentale a questo calcolo. Con term rate intendiamo i tassi LIBOR 1 mese, 3 mesi, 6 mesi, ecc.. Sono tassi osservabili oggi per operazioni con decorrenza oggi (o spesso in t+2) sulle varie scadenze. Sono quindi tassi detti anche forward looking, in cui la cedola indicizzata al tasso, o la rata del mutuo, utilizza il tasso osservato a inizio periodo, con logica nota come fixing in advance.

Bene, tutto questo si basa sulla osservabilità di una term rate fornita dai vari tassi LIBOR, che non esiste più in un contesto in cui i market data forniscono come dati “primitivi” i soli tassi Overnight.

Quale soluzione? Nuove convenzioni, nuovi modelli, nuovi prodotti? Il tema implica una notevole discontinuità con tutte le practice di mercato e rilevanti impatti su sistemi e procedure. Nella seconda parte della serie alcune risposte.

Ringraziamenti

Grazie a Paolo Cobuccio e Alessandro Santocchi, Iason Ltd, per il proficuo confronto.

Riferimenti

[1] Financial Stability Board (2014), “Reforming Major Interest Rate Benchmarks “.

[2] Financial Stability Board (2019), “Overnight Risk-Free Rates. User Guide ”

[3] Financial Stability Board (2019), “Reforming major interest rate benchmarks – Progress report “

[4] The Guardian (2015), “Libor scandal: the bankers who fixed the world’s most important number”ber

[5] The Working Group on Sterling RFRR (2020), “Use Cases of Benchmark Rates”

[6] ISDA (2020), “Adoption of Risk-Free Rates: Major Developments in 2020”, ISDA Research Notes.

[7] Schrimpf A., Sushko V. (2019), “Oltre il LIBOR: introduzione ai nuovi tassi di riferimento”, Paper BIS.

[8] Alternative Reference Rate Committee (2019), “Summary of ARRC’s LIBOR Fallback Language”.

[9] Unione Europea (2016), “Benchmark Regulation (BMR)”, Regulation 2016/1011.

[10] Banca d’Italia (2020), “La riforma dei tassi di riferimento del mercato monetario in euro”, disponbile sul sito www.baancaditalia.it

Sitografia

FSB, financial stability board,

ARRC, workig ngroup su risfors per Us, https://www.newyorkfed.org/arrc

EUR working group, https://www.ecb.europa.eu/paym/initiatives/interest_rate_benchmarks/WG_euro_risk-free_rates/html/index.en.html

GBP working group, https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/markets/transition-to-sterling-risk-free-rates-from-libor

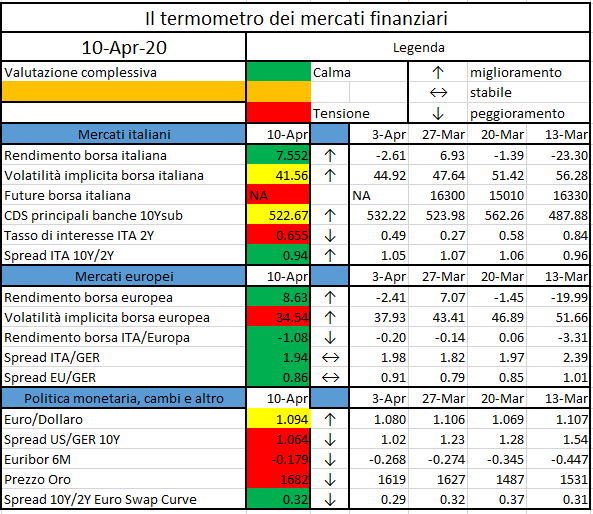

L’iniziativa di Finriskalert.it “Il termometro dei mercati finanziari” vuole presentare un indicatore settimanale sul grado di turbolenza/tensione dei mercati finanziari, con particolare attenzione all’Italia.

Significato degli indicatori

- Rendimento borsa italiana: rendimento settimanale dell’indice della borsa italiana FTSEMIB;

- Volatilità implicita borsa italiana: volatilità implicita calcolata considerando le opzioni at-the-money sul FTSEMIB a 3 mesi;

- Future borsa italiana: valore del future sul FTSEMIB;

- CDS principali banche 10Ysub: CDS medio delle obbligazioni subordinate a 10 anni delle principali banche italiane (Unicredit, Intesa San Paolo, MPS, Banco BPM);

- Tasso di interesse ITA 2Y: tasso di interesse costruito sulla curva dei BTP con scadenza a due anni;

- Spread ITA 10Y/2Y : differenza del tasso di interesse dei BTP a 10 anni e a 2 anni;

- Rendimento borsa europea: rendimento settimanale dell’indice delle borse europee Eurostoxx;

- Volatilità implicita borsa europea: volatilità implicita calcolata sulle opzioni at-the-money sull’indice Eurostoxx a scadenza 3 mesi;

- Rendimento borsa ITA/Europa: differenza tra il rendimento settimanale della borsa italiana e quello delle borse europee, calcolato sugli indici FTSEMIB e Eurostoxx;

- Spread ITA/GER: differenza tra i tassi di interesse italiani e tedeschi a 10 anni;

- Spread EU/GER: differenza media tra i tassi di interesse dei principali paesi europei (Francia, Belgio, Spagna, Italia, Olanda) e quelli tedeschi a 10 anni;

- Euro/dollaro: tasso di cambio euro/dollaro;

- Spread US/GER 10Y: spread tra i tassi di interesse degli Stati Uniti e quelli tedeschi con scadenza 10 anni;

- Prezzo Oro: quotazione dell’oro (in USD)

- Spread 10Y/2Y Euro Swap Curve: differenza del tasso della curva EURO ZONE IRS 3M a 10Y e 2Y;

- Euribor 6M: tasso euribor a 6 mesi.

I colori sono assegnati in un’ottica VaR: se il valore riportato è superiore (inferiore) al quantile al 15%, il colore utilizzato è l’arancione. Se il valore riportato è superiore (inferiore) al quantile al 5% il colore utilizzato è il rosso. La banda (verso l’alto o verso il basso) viene selezionata, a seconda dell’indicatore, nella direzione dell’instabilità del mercato. I quantili vengono ricostruiti prendendo la serie storica di un anno di osservazioni: ad esempio, un valore in una casella rossa significa che appartiene al 5% dei valori meno positivi riscontrati nell’ultimo anno. Per le prime tre voci della sezione “Politica Monetaria”, le bande per definire il colore sono simmetriche (valori in positivo e in negativo). I dati riportati provengono dal database Thomson Reuters. Infine, la tendenza mostra la dinamica in atto e viene rappresentata dalle frecce: ↑,↓, ↔ indicano rispettivamente miglioramento, peggioramento, stabilità rispetto alla rilevazione precedente.

Disclaimer: Le informazioni contenute in questa pagina sono esclusivamente a scopo informativo e per uso personale. Le informazioni possono essere modificate da finriskalert.it in qualsiasi momento e senza preavviso. Finriskalert.it non può fornire alcuna garanzia in merito all’affidabilità, completezza, esattezza ed attualità dei dati riportati e, pertanto, non assume alcuna responsabilità per qualsiasi danno legato all’uso, proprio o improprio delle informazioni contenute in questa pagina. I contenuti presenti in questa pagina non devono in alcun modo essere intesi come consigli finanziari, economici, giuridici, fiscali o di altra natura e nessuna decisione d’investimento o qualsiasi altra decisione deve essere presa unicamente sulla base di questi dati.

The European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), the EU securities markets regulator…