La normativa sui rischi degli investimenti dei clienti: una breve sintesi

La normativa di Basilea come noto è focalizzata sulla misura dei rischi dei portafogli delle banche, siano essi finanziari (market risk), sia legati alla attività di erogazione di prestiti, mutui e fidi (credit risk). La sua è una storia ormai trentennale. Una sintesi completa è disponbile in [3].

Negli ultimi 20 anni si è sviluppato prima in ambito nazionale poi comunitario un altrettanto importante corpo normativo con le relative prassi e procedure legato alla misura dei rischi degli strumenti finanziari collocati presso la clientela. Senza pretesa di esaustività ricordiamo alcuni degli eventi normativi salienti su questo aspetto nel nuovo millennio

- La disciplina nazionale sui FIA, fogli informativi analitici per la collocazione di obbligazioni strutturate, negli anni di grande sviluppo di questi strumenti (fine anni ’90, primi anni 2000)

- La Direttiva Prospetto europea (cfr. [4]) sul contenuto informativo dei prospetti per il collocamento di strumenti finanziari (azioni, obbligazioni, ..)

- La normativa MIFID (o MIFID I, cfr. [5]), che per prima ha disciplinato le esigenze di classificazione e profilazione della clientela, per fare in modo che siano rispettati opportuni vincoli di adeguatezza tra il cliente (disponibilità patrimoniale, conoscenze finanziarie, propensione al rischio) e l’investimento proposto dall’intermediario finanziario

- La normativa UCITS IV, sui fondi comuni, che ha disciplinato il contenuto di schede stadardizzate di informazione su costi, composizione e rischi degli OICR, requisti organizzativi, si veda [6]

A queste normative di primo livello sono corrisposte negli anni normative di II e III livello, tra cui in particolare le circolari e regolamenti Consob-Bankit.

Ricordiamo in particolare, con i suoi numerosi aggiornamenti, il regolamento congiunto Consob-Bankit ([7]) sui servizi di investimento e di gestione del risparmio, che disciplina in modo molto preciso anche le attività in carico alle funzioni di controllo delle banche (risk mgt, compliance, audit) sulla conformità alle normative dei processi aziendali di costruzione e collocamento dei prodotti e servizi.

In ambito extra normativo, però con effetti significativi in termini di dottrina e procedure, va ricordato il Quaderno Consob 63 (si veda [8]), per il dibattito suscitato in relazione all’uso di scenari probabilistici (contrapposti a un approccio what if) per la descrizione dei rischi degli investimenti.

Ricordiamo infine l’attività realizzata per alcuni anni da ABI con Patti Chiari sulle obbligazioni strutturate. Attività di pubblico servizio che ha prestato il fianco a numerose critiche, in quanto in sostanza catturava e misurava il rischio di mercato di uno strumento, ma non il rischio di default, o questo era troppo ancorato al rating. Questo dal caso dei bond Parmalat passando per il default Lehman sino ai bond subordinati (Popolare Etruria, ecc) ha portato alla fine alla chiusura del servizio, anche se il portale web è ancora nominalmente attivo.

Su questa storia articolata e in parte disomogenea tra il mondo degli strumenti di base (azioni, obbligazioni) e quello del risparmio gestito (fondi, sicav, prodotti assicurativi con contenuto finanziario quali le polize index e unit linked) si innestano dal 2.1.2018 due normative di fondamentale importanza: MIFID 2 e PRIIPS.

MIFID 2 rafforza gli strumenti di tutela del cliente, esprimendo nuovi concetti quali la product governance (l’intermediario deve avere presente e dichiarare il target di riferimento del prodotto), dall’altro rendendo più rigidi principi già stabiliti in MIFID, quali i casi di esonero dell’intemediario da responsabilità in regime di execution only, o i criteri di preparazione professionale dei dipendenti impegnati in servizi di consulenza.

La normativa PRIIPS (si veda [10]), detta anche “KID for PRIIPS”, disciplina il documento standard KID (key information document) per i prodotti finanziari retail e insaurance based, con le informazioni che deve recare in 3 pagine, altamente standardizzate, in ordine a:

- Struttura generale del prodotto e dati anagrafci

- Costi

- Scenari di performance

- Rischi

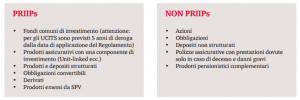

Importante da subito osservare cosa rientra nel perimetro dei PRIIPS, come dalla tabella che segue:

Come riportato in tabella, i fondi comuni già sottoposti a UCITS hanno 5 anni di deroga, ma verosimilmente il loro documento standard, che nel gioco delle “i” si chiama “KIID”, sarà riportato alle regole del “KID”.

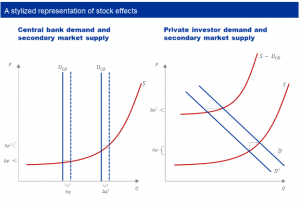

Le Misure di Rischio. Una generalizzazione concettuale

E’ opinione diffusa non corretta che fare Risk Management sia quasi esclusivcamente una questione di scelta modello probabilistico per l’evoluzione dei mercati, quindi dei prezzi e dei fattori di rischio, e di scelta della misura per tradurre in senso numerico il termine “rischio”. In tal senso ha forse nuociuto la discussione ventennale nella comunità finanziaria tra VaR (un quantile) ed Expected Shortfall (la media della perdita sui soli casi estremi), che ha messo in secondo piano altri aspetti essenziali del processo di controllo del rischio. Cerchiamo di astrarre dai casi specifici per rappresentare nel seguito tutti gli elementi di tale processo.

- Misura teorica. Si è già detto di questo, e come noto nel market risk sono VaR ed ES i due pincipali competitors. Ma molte altre sono le proposte possibili con buona diffusione nella prassi. Per esempio, la volatilità stessa è un popolare indicatore di rischio nel campo dell’asset management. Sempre nell’asset management, si usano spesso misure ex-post quali max drawdown, cioè la massima escursione negativa di un prezzo in un dato periodo. Oppure vanno ricordate le misure di decomposizione del rischio. Per esempio il ComponentVaR misura in che parte uno strumento o sub-portafoglio contribuisce al VaR dell’intero portafoglio. Infine anche gli stress test sono una misura di rischio. Negli stress test la logica probabilistica viene sostituita da un approccio what if, cioè quanto si perde nell’investimento se una evento estremo si verificasse, evento a cui non necessariamente viene attribuita una probabilità. A questo approccio sono collegate misure molto diffuse in ambito gestionale nei portafogli proprietari delle banche, si pensi alla duration o al bpv (basis point value), cioè di quanto cambia il valore di una posizone/portafoglio se la curva dei tassi si sposta di 0.01%. Misure molto utili anche per coperture in base al “rischio aperto”

- Parametri della misura. Con che parametri viene applicata la misura? Nel caso del VaR i parametri tipici sono l’orizzonte (holding period) e il livello di confidenza Questi parametri riflettono il livello di prudenza che il regulator o le prassi gestionali usano per dare concretezza al concetto di rischio. Esempio: mentre nel rischio di mercato la normativa Basilea II-III richiede un livello di confidenza del 99%, nel rischio di credito per i modelli interni è richiesto un VaR al 99.9%, anche per tenere conto di possibili incertezze sui parametri, rischio modello, ecc. Al contrario in ottica gestionale non è infrequente l’uso di un VaR con livello 95%. Ci si preoccupa cioè di livelli di perdite con un livello di prudenza/pessimismo più moderato.

- Modello probabilistico del mercato. Questo aspetto ha a che fare con la dinamica dei prezzi degli strumenti finanziari o dei fattori di rischio che compongono il portafoglio. Se si calcola il VaR utilizzando i punti za della variabile gaussiana, è perché si ipotizza una distribuzione gaussiana dei rendimenti. Se viceversa si applicano ai valori correnti i rendimenti storici e poi si determina il quantile empirico dela distribuzione dei valori, si è nel caso opposto di approccio non parametrico (più noto nel settore come historical simulation), cioè non si fa alcuna ipotesi sulla forma dei rendimenti e si considera che il loro istogramma empirico ne sia la migliore stima

- Algoritmo calcolo della misura. Fissati gli elementi precedenti, quindi a parità di misura e di modello, ci possono essere differenti metodi di calcolo della stessa, per questioni di proprietà statistiche nell’ ultimo step del calcolo. Esempio: Se si usano i metodi di historial simulation o simulazione montecarlo e si dispone di 473 osservazioni, il VaR 99% potrebbe essere stimato campionando il 4^ peggiore risultato, il 5^ peggiore, cioè con delle stime empiriche in un caso più prudente e nell’altro più fair del quantile teorico. Oppure visti i noti problemi di instabilità (elevata varianza) dei quantili empirici “puntuali”, si può utilizzare una media pesata del 4^ e 5^ peggiori scenari o in un intorno ancora più ampio.

- Scomposizione/granularità della misura. Spesso in letteratura accademica è normale scrivere “Il VaR” o “L’expected shortfall”. Ma sarebbe più corretto scrivere “I VaR”. In altri termini, fissata la misura questa viene calcolata in condizioni e aggregati differenti. Esempi: nella normativa di Basilea le asset class (tasso, cambi, equity) determinano una pluralità di misure, in cui il rischio viene analizzato congiuntamente ma anche con riferimento al distinto contributo delle diverse asset class. Sia nei portafogli proprietari sia nel risparmio gestito si calcolano misure di rischio sul singolo strumento/posizione sia sull’intero portaffoglio o sub-portafoglio. La futura normativa sui rischi di mercato, FRTB, richiede di calcolare ES su tutte le possibili combinazioni di asset class e liquidity horizon secondo la tassonomia assegnata ai fattori di rischio.

- Scopo della misura. Una misura senza alcun feedback nei processi ma solo rappresentata nel reporting sarebbe poco utile, si tratterebbe poer l’appunto solo di misura senza “controllo” o “gestione”. Possiamo distinguere i seguenti utilizzi delle misure:

- Adeguatezza patrimoniale (Basilea). Si verifica cioè se il patrimonio della banca può sopportare le perdite potenziali stimate con le misure di rischio

- Adeguatezza/Classificazione (MIFID/PRIIPS). Lo strumento in base alla sua misura numerica è classificato in diverse classi (7 nella normativa PRIIPS), e questo permette di verificare in termini di compliance se lo strumento o l’intero portafoglio è adeguato per il profilo del cliente

- Limiti (gestionale). Le banche nei portafogli proprietari e gli asset managers (nei prospetti o con limiti interni) fissano vari limiti di massimo rischio in capo ai diversi livelli di reponsabilità nella gestione del portafoglio, un vero e proprio albero dei limiti. All’eventuale mancato rispetto di questi limiti sono legati processi di rientro (cioè chiudere le posizioni per rientrare nel limite) o di approvazione, mediante un processo di escalation gerarchica che in relazione ai vari casi può richiedere l’intervento dei vertici apicali o del CDA.

Confronto tra misura dei rischi finanziari Basilea vs PRIIPS

In che misura i processi di Risk Management regolamentari, per compliance alle diverse regulattion, sono liberi di effettuare le scelte interne? O si tratta di processi regulator driven con stretti obblighi di compliance? Rispetto agli elementi descritti nel paragrafo precedente, riportiamo una tabella di confronto tra la normative di Basilea, ambito market risk, e PRIIPS.

| Drivers Controllo rischio |

PRIIPS |

BASILEA |

| Misura rischio |

Value at Risk |

Value at Risk attualmente, Expected Shortfall nella normativa FRTB |

| Parametri misura |

Confidence level a = 97.5%, poi questo dato viene ricondotto a una VEV = volatilità annualizzata. Infine viene anche definito RHP = reccomended holding period |

Confidence level a = 99%, Holding Period h = 10 days. Poi mediante coefficiente moltiplicativo b la misura è riscalata (Beta tra 3 e 4) |

| Algoritmo di calcolo |

Regulation given. Per i prodotti lineari (senza garanzie capitale o opzionalità) si utilizza l’approssimazione del quantile di CornishFischer. Per prodotti con payoff non lineari va effettuata una simulazione montecarlo con 10.000 paths su cui poi stimare il quantile |

Le banche possono utilizzare qualunque modello: modello non parametrico (historical simulation) o parametrico (tipicamente gaussiano) per i fattori di rischio, o anche approssimazioni analitiche come le delta-gamma-vega. La qualità predittiva del modello è monitorata con backtesting delle P&L effettive vs il VaR ex ante. |

| Scomposizione Segmentazione |

Il VaR del prodotto non è decomposto. I prodotti sono però classificati in 4 categorie con regole di calcolo diverse: 1) prodotti complessi (e.g. derivati) o senza serie storiche 2) Prodotti lineari (e.g. unit linked e fondi plain) 3) Prodotti non lineari (e.g. prodotti con garanzia capitale) 4) Prodotti che dipendono da parametri non osservabili (e.g. da indicatori bilancio dell’azienda emittente) |

L’enfasi è sul rischio di portafoglio, non della singola posizione. Questo è però decomposto (con somma finale senza effetto diversificazione) in asset class come segue: rischio di tasso, rischio spread, rischio equity, rischio forex, rischio commodity. Nella normativa FRTB di futura applicazione oltre alle asset class (AC) si tiene conto dei liquidity horizon (LH), con un set più granulare di segmentazione della misura |

| Scopo misura |

Al prodotto viene assegnata una classe di rischio finanziario tra 1 e 7 (massimo rischio) in base ad altrettanti classi di volatilità. Qesta va poi confrontata con il profilo di rischio del cliente per verificare l’adeguatezza cioè la compatibilità con il suo portafoglio. |

La misura di rischio di mercato, oggi data da VaR e VaR stressato moltiplicato per coefficiente beta, viene sommata al rischio di credito e operativo. La somma dei rischi deve essere minore o uguale agli own funds (patrimonio della banca) in base al primo pilastro di basilea, che prescrive che debba essere il patrimonio a fare fronte alle perdite (estreme), di cui la misura dei rischi fornisce una stima ex ante. |

Riflessioni e Conclusioni

A parte le intuibili differenze nell’utilizzo pratico delle misure di rischio e nella segmentazione delle stesse, la vera differenza significativa nel confronto Basilea vs PRIIPS è che nel contesto PRIIPS non solo la misura ma anche il modello/algoritmo, sino alla lunghezza delle serie storiche richieste per la stima dei parametri, è totalmente prescritto dal regulator.

In questo ravvisiamo alcuni razionali comprensibili. Se la tutela di tutti gli stakeholder in particolare depositanti è importante nella verifica di consistenza del patrimonio delle banche (Basilea), ancora di più 15 anni di gravi casi di perdite subite dai clienti nei loro portafogli per mancata tutela suggeriscono una normativa molto dirigistica in ogni dettaglio del calcolo. Questo in relazione alla alea da modello che anche nel contesto di “Basilea 4” sta portando a ridurre l’autonomia dei modelli interni.

Sul fronte dei punti di attenzione, le 4 categorizzazioni previste in PRIIPs con altrettante tecniche di misura hanno punti di confine non sempre chiarissimi nella loro effettiva applicazione. Inoltre, su un piano strettamente tecnico, appare in alcuni casi debole (cioè per alcune distribuzioni dei rendimenti) l’uso della approssimazione analitica del quantile con il metodo di Cornish-Fiscer, si veda [11].

Certo si doveva regolamentare e l’impianto generale è rigoroso e fair. Vedremo nei prossimi mesi in che misura anche le reti di di vendita e consulenza sapranno migliorare e rendere più sostanziale la relazione con il cliente con questi nuovi KIDs.

References

[1] Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2014), “Fundamental review of the trading book: outstanding issues”, paper 305.

[2] Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2016), “Minimum capital requirements for market risk,”, paper 307.

[3] Bonollo M. (2017), “30 anni del percorso della regolamentazione di Basilea. Un tentativo di sintesi”, https://www.finriskalert.it/?p=5161.

[4] European Parliament (2003), “Directive 2003/71/EC – prospectus to be published when securities are on sale to the public or admitted to trading”, Official Journal of the European Union.

[5] European Parliament (2004), “Directive on markets in financial instruments 2004/39”, Official Journal of the European Union.

[6] European Parliament (2009), “UCITS IV, regulation 2009/65”, Official Journal of the European Union

[7] Consob-Bankit (2007), “Regolamento in materia di organizzazione e procedure degli intermediari che prestano servizi di investimento o di gestione collettiva del risparmio (Testo integrato e aggiornato al 20 marzo 2015)”.

[8] Minenna M. et al. (2009) “Un approccio quantitativo risk-based per la trasparenza dei prodotti d’investimento non-equity”, Quaderni di Finanza Consob, n.63.

[9] European Parliament (2013), “Capital requirement regulation n.575” (Basel III)”, Official Journal of the European Union.

[10] European Parliament (2014), “Regulation 1286/2014 \Key information documents for packaged retail and insurance-based investment products (PRIIPs)”, Official Journal of the European Union.

[11] Tesser M. et al (2017), \Packaged Retail Investment and Insurance-based Investments Products (PRIIP) – Scenari di performance con traiettorie alla Cornish-Fisher”, Working Paper Department of Economics, University of Verona WP, n.11.