Tra le “buzzword” del momento, troviamo certamente “robo-for-advisor”. Ovvero strumenti d’analisi e costruzione di portafoglio in dotazione ai relationship manager. È tecnologia a supporto del professionista: lo potenzia, a tutto beneficio di produttività e qualità del servizio al cliente. Sembra essere il connubio uomo-tecnologia ottimale, visto che i roboadvisor puri sono relegati a una nicchia di mercato destinata a rimanere tale per un po’ e visto che “the human touch” sembrerebbe ineliminabile, almeno per ora.

Bello, in teoria.

In pratica, però, ho notato che svariate istituzioni finanziarie sono rimaste un filo indietro. E così sono corse ai ripari, magari sulla spinta delle reti, dotando in fretta e furia i loro relationship manager – ossia private banker, consulenti finanziari dipendenti e indipendenti, operatori di filiale – di strumenti di portfolio construction. Ne ho visto diversi, buoni e meno buoni. Molti soffrono di un (antico) problema sul quale mi sento di condividere alcune riflessioni.

Un antico tormentone

Il problema, che riemerge periodicamente (accadde già con la prima ondata di roboadvisor), è che gran parte di questi sistemi di robo-for-advisor si basano sull’applicazione naïve della Modern Portfolio Theory di Markowitz, in breve naïve-Markowitz.

È inquietante osservare come, a sprezzo di circa trent’anni di ricerca accademica, l’Homo sapiens riesca ad essere così superficiale da trasformare in pattume pseudoscientifico un’idea illuminante e geniale – in questo caso quella seminale di Harry Markowitz, che consisteva nel ricercare esplicitamente il trade-off tra rischio e rendimento, facendo tesoro di tecniche di programmazione matematica. Purtroppo, il naïve-Markowitz è invece metodologicamente agghiacciante, nonché praticamente pericoloso per i clienti, per i professionisti e per la reputazione delle azienda. Vediamo perché.

L’inghippo è che il processo naïve-Markowitz è semplice, ma dall’apparenza scientifica: si definisce l’universo investibile (asset class, fondi, etf, ecc), si prende qualche anno di serie storiche, se ne ignora bellamente la distribuzione di probabilità empirica, ipotizzando invece che sia gaussiana, poi si stimano a massima verosimiglianza dalla storia i parametri (matrice di covarianza e vettore delle medie), si sbatte tutto in un risolutore per problemi di programmazione quadratica, infine si pigia il bottone. Et voilà! S’ottiene la mitica frontiera efficiente dei portafogli, con tanto di curva scenografica e rendimenti attesi specificati al secondo numero decimale, magari anche al terzo, a seconda del software.

C’è però un problema: quei portafogli non hanno senso. Se non per caso. Letteralmente: i pesi di portafoglio sono de facto casuali.

Questo perché l’errore di stima dei parametri è tipicamente di tipo “monster[1]”. Inoltre i portafogli si fondano su una storia che probabilmente non si verificherà più. Infine, le ipotesi sottostanti sono lontane dalla realtà (i rendimenti arcinotoriamente non seguono affatto una distribuzione gaussiana e i parametri del “data generation process” non restano costanti nel tempo) – ma questo, lasciatemi dire, è il minore dei mali.

È intuitivo che, là fuori nel mondo reale, siffatti portafogli qualche problema siano destinati ad averlo. Così, alle prime legnate prese dai mercati, tutto sembrerà assai meno scientifico, tra le belluine proteste di clienti e le lamentele dei consulenti (“il sistema di robo-for-advisor non funziona”).

Sospetto che molti di voi ritengano che mi stia arrovellando intorno a una sottile questione tecnica, irrilevante nella pratica. Niente di più sbagliato: è sì una questione tecnica, ma tra poco, numeri alla mano, vi mostrerò la vastità del problema nella pratica. Cioè gli impatti di business.

In ogni caso, alla radice del problema non c’è la sfortuna dell’investitore e del suo consulente, bensì il “butterfly effect, cioè l’effetto farfalla, ben noto a priori se uno .

The butterfly effect

Si tratta di un rimarchevole concetto nativo della teoria del caos e dei sistemi complessi. L’idea, che probabilmente conoscete, è espressa coereograficamente così: un batter d’ali di una farfalla in Brasile può causare una catena di eventi nell’atmosfera tali da provocare un tornado in Texas. Generalizzando, piccole variazioni nelle variabili di un sistema possono arrivare a causare grandi effetti.

È proprio ciò che capita con i modelli naïve-Markowitz: gli errori nella stima degli input si fanno strada negli algoritmi che portano all’asset allocation finale, crescono e finiscono con avere un impatto enorme, tale da inficiare del tutto la validità dell’output. Tanto che l’applicazione del naïve Markowitz è nota come “maximization error model”. Siccome l’idea è un po’ cerebrale, tocchiamola con mano grazie ad un esempietto numerico.

Immaginate di essere il dio dei mercati finanziari. Considerate 25 asset class, per le quali bonariamente imponete che la distribuzione di probabilità dei log-rendimenti mensili sia gaussiana, con volatilità crescente da 1% a 25% e Sharpe ratio pari a 0.3 per tutte le asset class, matrice di covarianza a correlazione costante (ipotesi utili per creare un esempio ragionevole e comprensibile, nient’altro).

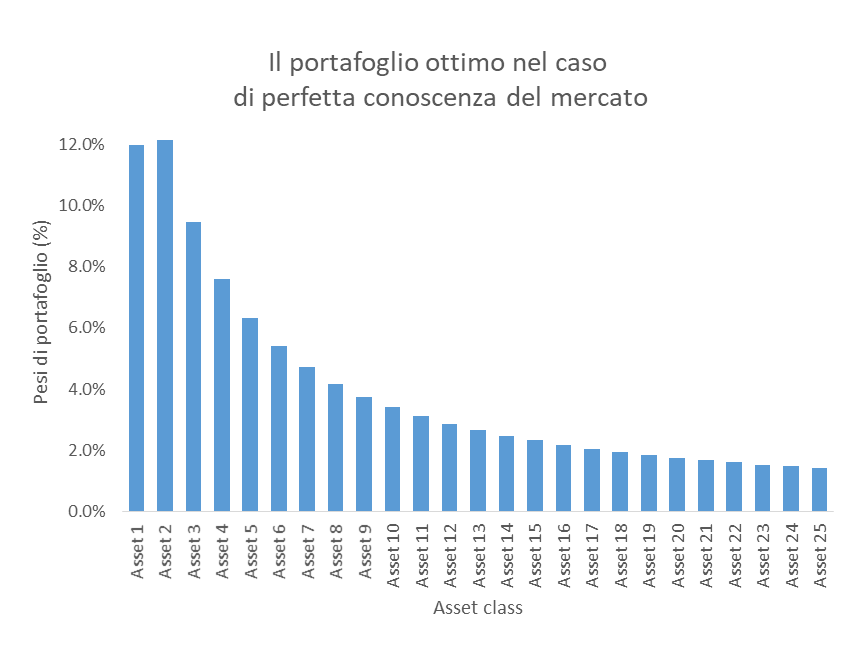

In queste condizioni, per un profilo di rischio medio, un portafoglio “ottimo” long-only secondo il modello naïve Markowitz ha i pesi delle varie asset class (ordinate in funzione della volatilità) mostrati nella figura seguente.

Già ad occhio il portafoglio sembra piuttosto ragionevole: i pesi sono ben distribuiti, le attività meno rischiose pesano di più (rammento che è un portafoglio a rischio medio), circa il 50% del portafoglio, mentre gli attivi più volatili cubano per un 20% circa. L’indice di diversificazione è 96%, altissimo.

In questo mondo immaginario questa è la verità assoluta, perché non c’è alcun errore di specificazione, legato alla scelta del modello, né errore di misura (stima) dei parametri: siamo di fronte al “vero” portafoglio ottimo.

Ora cambiamo prospettiva: siete un sistema di robo-for-advisory al quale viene dato in pasto un campione di cinque anni di dati generati dalla distribuzione di probabilità di cui sopra, quella del dio del mercato. Date le ipotesi, si può dimostrare come l’errore di specificazione del modello sia pari a zero. C’è solo errore di misura, puro errore campionario. Calcolate di nuovo i pesi ottimali secondo naïve Markowitz e li mettete da parte.

Poi, come in preda a un rewind temporale, vi vengono forniti altri 5 anni di dati generati sempre dalla stessa distribuzione multivariata. Un altro campione. Un altro “mondo possibile”. E così ripetete l’esercizio.

E ancora, per 10mila volte, 10mila scenari possibili.

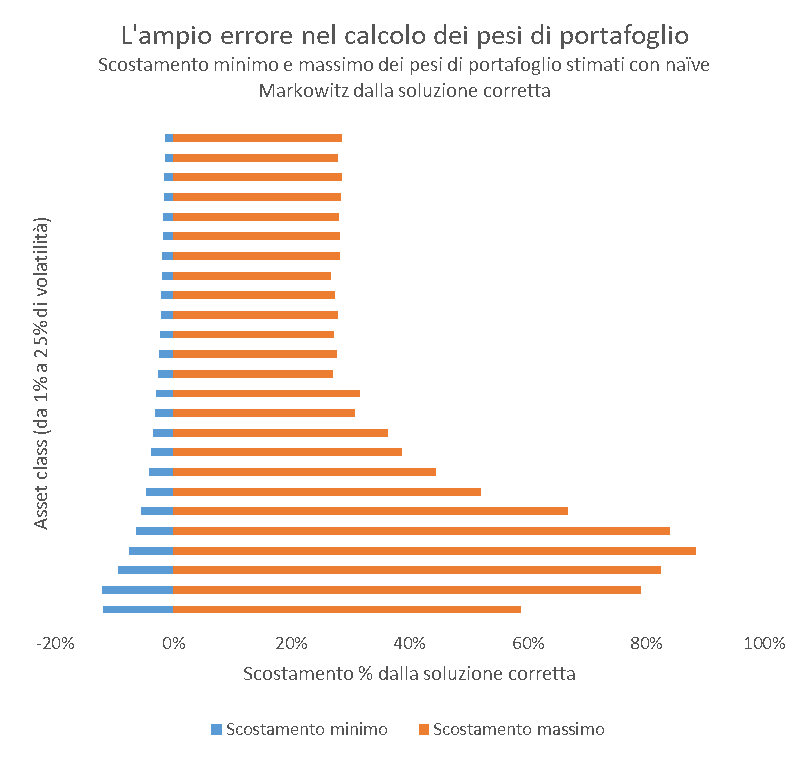

Ora vediamo nel grafico seguente quanto si scostano i pesi di portafoglio stimati da quelli veri: per ogni asset class riporto l’intervallo che contiene gli estremi di variazione degli scostamenti. L’errore commesso rispetto al portafoglio “del dio” varia allegramente dal -12% a poco meno del 90%. L’indice di diversificazione di questi portafiogli ha valore mediano pari a 35% (rammneto che quello “vero” è 96%), il che vuol dire che l’idea stessa di diversificazione è largamente compromessa.

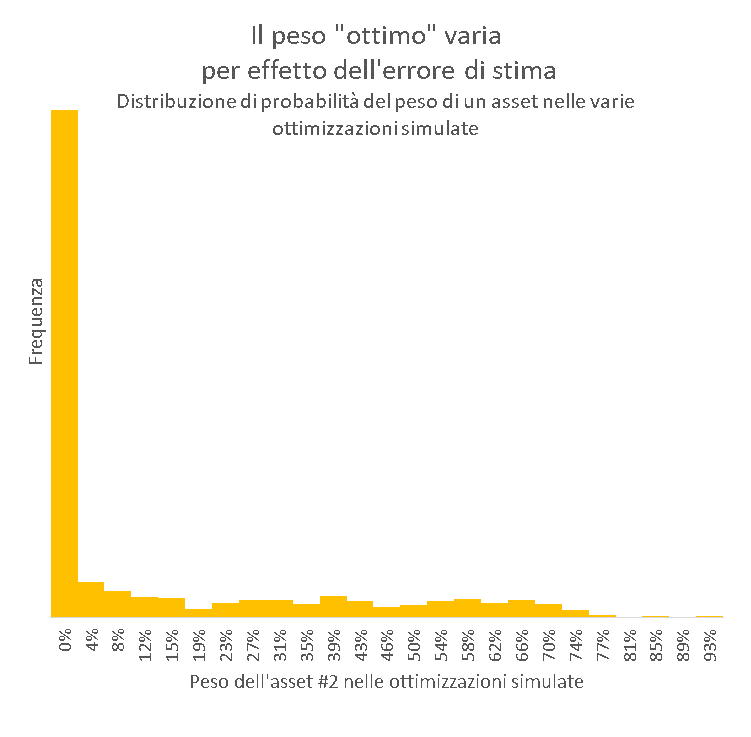

Se consideriamo per esempio l’asset 2 (a basso rischio, con volatilità 2% e rendimento atteso 0.6%), nel portafoglio ottimo “vero” il peso è 12%. Guardate invece come oscilla nelle varie ottimizzazioni fatte dal robo-for-advisor: assume sovente valore 0%, e qualsiasi valore ammissibile, arrivando anche a dominare il portafoglio. Non stupisce che la diversificazione vada gambe all’aria.

Penso vi sia chiara la madornale portata dell’errore associato al naïve Markowitz e la ragione dell’appellativo “maximization error model”: l’errore di stima genera portafogli casuali come quelli che potrebbe generare una scimmia. Non si tratta di mancanza di finezza matematico-statistica. No. Si tratta di risultati casuali e instabili (per chi è matematicamente orientato, per avere un’idea analitica dell’instabilità basta dare un’occhiata alla matrice jacobiana contenente tutte le derivate parziali dei pesi ottimi nella soluzione in forma chiusa di Markowitz, cioè w*, rispetto al rendimento atteso m, ossia ∂w*/∂m). Numeri spesso lontanissimi dalla vera soluzione ottima e quindi praticamente privi di valore. Classico “garbage-in, garbage-out”.

E considerate che la realtà è ben peggiore di così: nell’esempio c’è solo e soltanto l’errore legato alla stima campionaria, mentre nella pratica c’è anche un sostanzioso errore legato alla specificazione del modello, al quale s’aggiunge il fatto che i parametri di mercato cambiano di continuo.

Spero sia ora evidente quale immensa idiozia siano quelle belle frontiere efficienti e quei rendimenti attesi specificati al secondo decimale.

Utilizzare naïve Markowitz così – proprio ciò che stanno facendo con entusiasmo molti consulenti finanziari e private banker – alla fine della fiera porterà a una sola cosa: una disastro, per di più non facilmente spiegabile al cliente.

E quando si verificheranno i disastri, di chi sarà la colpa? Del roboadvisor/motore di portfolio construction in primis, in solido con il consulente che ci mette la faccia e con la casa madre che ha messo in piedi il baraccone. Un bel rischio operativo.

Soluzioni?

C’è una buona notizia: si può evitare di sprecare budget in una raffinata macchina per produrre spazzatura finanziaria e dare invece qualche strumento agli advisor.

I meta-ingredienti occorrenti sono due:

- una metodologia, che non può essere un singolo modello one-size-fits-all, bensì una “ricetta d’investimento” fatta di una combinazione di metodi di portfolio construction e stimatori robusti, inseriti in un processo d’investimento razionale, disciplinato e finanziariamente ben fondato, con uno storytelling chiaro nel confronti del cliente;

- un governo centrale e competente del processo, che parta dalla casa madre. Senza un metodo solido e un presidio forte sulla costruzione dei portafogli è inevitabile che qualche consulente finanziario o private banker con l’indole del Warren Buffet della Brianza o del Ray Dalio della Ciociaria prima o poi combinerà qualche disastro.

Non è difficile fare le cose per bene. Occorre solo

conoscenza di processo e un po’ di know-how teorico-pratico di modellizzazione statistica

e finanziaria che vada oltre Markowitz e uno scolastico Black-Litterman. Sfortunatamente,

sembra che non poche organizzazioni ne siano sprovviste.

[1] Questo problema è ampiamente riconosciuto e studiato, sia teoricamente che empiricamente; si vedano, tra i molti, Best e Grauer (1991), “On the Sensitivity of Mean Variance Efficient Portfolios to Changes in Asset Means: Some Analytical and Computational Results”, Review of Financial Studies, nonché Chopra e Ziemba (19939, “The Effects of Errors in Means, Variances and Covariances on Optimal Portfolio Choice”, Journal of Portfolio Management.