Institutional investors play a key role in financial markets’ development. They represent the world’s largest source of equity capital and contribute to both efficiency and modernization of the allocative mechanisms of a financial system. Moreover, active institutional investors may foster an improvement in corporate governance practices by monitoring firm management.

The policy debate has recently highlighted increasing concerns about the role of institutional passive investors. Among the others, the IMF has warned about the potentially destabilizing effects of their asset allocation strategies, given that herding behavior may contribute to assets bubbles.

According to the OECD, at the end of 2015 investment funds’ assets under management represented about 104% of GDP in the US, up from nearly 72% at the end of 2008. Over the same period, they reached 56% from 34% in Germany, around 71% from 68% in France, while lagging behind in Italy, where they accounted for slightly more than 17% of GDP (from 13%).

Given the size and the role of institutional investors, understanding the drivers of asset managers’ allocation decisions, and in particular of equity allocation in listed firms, is fundamental on policy grounds, in order for regulators to provide the proper incentives towards virtuous behavior and to address the potential risks posed by the aggregate dynamics of these players in financial markets.

Consob Working paper n. 86 contributes to the literature on the determinants of institutional investors’ equity holdings with respect to 500 large non-financial listed companies in five major European countries (France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom) over the period 2010-2015 (http://www.consob.it/web/area-pubblica/quaderni-di-finanza).

Applying a fixed effect panel and a fractional regression model to actively managed funds referable to three categories of institutional investors, i.e., mutual funds, sovereign funds and hedge funds, the study finds evidence that both country-specific and firm-level characteristics play a relevant role in active institutional investors’ decisions.

The data

Our data set includes the end-of-year aggregate shareholdings of active institutional investors (i.e., mutual funds, sovereign funds and hedge funds) in each sample firm, as drawn from Thomson Reuters. For each country, the major 100 listed non-financial companies are considered. Direct shareholdings of financial institutions such as banks and insurance companies were excluded, since their asset allocation choices might be driven by different factors from those influencing ‘pure’ asset managers’ investment strategies. Moreover, passive institutional investors were excluded, given that they replicate some index or benchmark return and therefore assign less relevance than active investors do to macro or company-level characteristics.

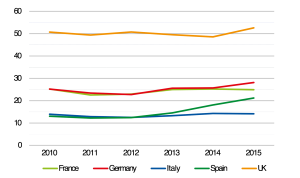

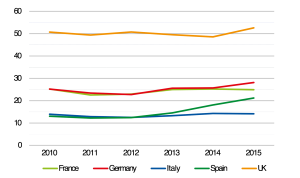

Over 2010-2015, institutional investors’ holdings represent on average about 26% of shareholders’ equity. Mutual funds are the largest category among all active institutional investors (with an average of nearly 20.5% equity holdings), while sovereign and hedge funds are marginal. The presence of institutional investors, however, vary a lot across countries, ranging from an average of 13.5% in Italy to nearly 50% in the UK. This evidence mirrors the well-known differences across European financial systems in terms of role of institutional investors and stock market development. Over time, institutional ownership has remained fairly stable in Italy and France, while rising in Spain, in the UK and to a lesser extent in Germany (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Institutional investors’ shareholdings across the main European countries (2010-2015; data refer to mutual funds, sovereign funds and hedge funds; percentage values)

Source: elaboration on Thomson Reuters data

In order to analyse the determinants of institutional equity holdings, both country-level variables and firm-level variables were included. Country-level variables comprise GDP growth, as an indicator of economic development, and debt to GDP ratio, as a proxy of country risk. Stock market development is captured by total exchange capitalization to GDP, whose values range over the sample period from a minimum of 20.2% in Italy to a maximum of 112.6% in the UK. Finally, the efficiency of the legal and judiciary system is taken into account by including among the explicative country-level variables the insolvency recovery rate and the number of days required to enforce a contract. These indicators also show a striking variability across jurisdictions, as the recovery rate is equal to about 57% in France, followed by Italy at 62%, and to about 89% in the UK, whereas the judiciary enforcement of a contract records Italy as the worst, with 1,183 days, and France as the best, with about 393 days.

As for company-level variables, both market and profitability and financial indicators are included, i.e., market capitalization, free float, share of the first shareholder (as a proxy of corporate control contestability), price-to-book value, dividend yield, return on equity (Roe), sales growth, leverage. Also several indicators accounting for the quality of corporate governance are incorporated, such as CEO duality (i.e., the CEO acting also as a chairman), board size, board members’ attendance rate, percentage of independent directors on board, presence of the compensation and nomination committees, percentage of independent directors sitting in board committees, and a synthetic corporate governance score provided by Bloomberg.

Results

In order to analyze the determinants of institutional shareholdings, first a standard panel fixed effect model is estimated. As a robustness check, a fractional regression model was run too, after normalizing institutional holdings within the [0,1] interval, in order to account for possible censoring of the dependent variable.

For each model, several specifications are tested, including either a subset of regressors, or a mix of country-level and company-level indicators. Some specifications include also time dummies in order to control for aggregate fluctuations of institutional ownership over time, due to market turmoil, changes in European regulation, technological progress, etc.. Each specification is reiterated for each class of institutional investors (i.e., mutual, hedge and sovereign funds), in order to control for differences in their business model.

The results of the fixed effect regression for the institutional investors as a whole are in line with previous empirical evidence, as investors are found to prefer listed companies in countries with higher GDP growth, lower debt-to-GDP ratio and more efficient legal systems.

As for firm-level variables, common indicators such as liquidity (proxied by free float), profitability and financial leverage are statistically significant, at least in some specifications.

The evidence for corporate governance variables is less conclusive (possibly due to missing data), except for board size, recording a negative impact, and the percentage of independent directors, which is estimated to have a positive impact. Overall, less cumbersome and more independent boards seem to be appreciated by institutional investors. Further corporate governance variables (e.g., CEO duality, a synthetic governance quality score) turn out to be statistically significant when the fractional regression is run. With respect to the impact of corporate governance, however, further investigation might be needed in order to test whether good governance is endogenous to institutional holdings, i.e., whether it is the presence of active asset managers in a listed company to raise governance quality rather than the other way round.

Finally, some specifications concerning sovereign and hedge funds equity holdings seem to defy conventional wisdom (e.g., the GDP growth is estimated to have a negative impact). However, this evidence might be consistent with the contrarian investment policy followed by many hedge funds, whose raison d’etre often consists in betting (and hence, taking positions) against mainstream market views.