The financial system is undergoing a more and more important, pervasive and disrupting technological evolution.

Most of the financial market players are evolving their business models into a FinTech direction, leveraging on the more efficient, independent and flexible technology which is able to learn through an iterative process of self-learning and error correction.

Following the recent 2008 financial crisis, the Supervisory Controls on behalf of Regulators have become more pervasive, detailed and intransigent, recording cumulative penalties for ca. $ 200 bn since 2008 because of the failures to regulatory requirement compliance (Douglas, Janos, & Ross, 2016).

The fear of a new light supervision over banking activities along with a worsening of the financial markets health have suggested an enlarged scope of regulatory requirements and greater reporting effort, data disclosure and data quality processes.

RegTech addresses these needs by introducing in a cost-effective and simple way, a new technology that is able to offer flexibility in data and report’s production, automation in terms of data quality, improvement in data management for analysis and inspections purposes (e.g. cognitive learning applied to RAF).

However, RegTech implies significant changes in compliance approach for banking institutions and consequently, it places new challenges to Regulators’ infrastructural capabilities. Supervisors are involved in this disrupting process, they have to acquire technological and analytical tools able to process and analyze an increasing amount of data requested.

RegTech: an evolving framework

Regulatory developments in action

New regulations, introduced as a consequence of the recent financial crisis, have increased controls of financial institutions both in terms of banking prudential capitalization (minimum capital requirement for operational, credit and market risks under Basel III, FRTB) and data disclosure for Regulators and customers (MiFID II, PSD 2).

The rationale behind these changes is to determine a homogeneous capitalization scheme among all banks in order to provide Supervisor with the chance to compare and efficiently aggregate banking risks and to achieve an overall picture of the banking system.

In this context, the standard models, as well as tests under stressed conditions, will become mandatory for all banks (including those that use internal models and therefore necessarily adapted to their needs) and represent the regulatory floor to RWA. For this purpose, a set of widespread exercises (EBA Stress Tests) and inspections (TRIM) have been set up.

In this fast evolving framework, banking institutions are experiencing an inevitable growth of the burden of analysis, reporting and public disclosure of their status towards Supervisors, resulting in greater economic expenditures and IT architecture developments

Digitalization: FinTech transformation in the FSI industry

In order to grasp the new opportunities available on the market, Financial Industry is progressively increasing the use of technology in various areas at different levels where it is involved, for example payment service, digital banking and lending.

These new technologies applied to the financial world is now called FinTech. Different sub-sectors of Financial Industry can benefit from the development and application of this new science such as:

- Artificial Intelligence

- Blockchain

- Cyber Security

- BigData

RegTech Information

The RegTech has been identified, for the first time, by FCA (Financial Conduct Authority) (Imogen, Gray, & Gavin, 2016) as “a subset of FinTech that focuses on technologies that may facilitate the delivery of regulatory requirements more efficiently and effectively than existing capabilities”. It addresses both the need of banking institutions to produce, as fast as possible, reports for regulatory requests and the creation of a new framework between Regulator and financial institution, driven by collaboration and mutual efficiency.

RegTech is becoming the tool to obtain a greater sharing of information between the parties, by reducing the time spent to produce and verify data and by performing jointly analyses, both current and prospective through mutual skills.

Implications for banking institutions

RegTech will allow institutions to develop a new way of communicating their data to the control authorities and to the whole financial system by exploiting a more efficient Risk Management and an advanced Compliance management.

Digital Compliance

The RegTech Council (Groenfeldt, 2018) has estimated that, on average, the banking institutions spend 4% of their revenues in activities related to compliance regulation and, by 2022; this quote will increase by around 10%. In this area, the transition to an advanced and digital management of compliance would bring around 5% of cost-savings. Concerning the new regulations introduced for trading and post trading areas, the RegTech would help managing the huge amount of data referred to transactions, KPI, market data and personal data related to customer profiling.

Particularly, a Thomson Reuters survey (Reuters, s.d.), has estimated that, in the 2017, the process of information checking of new users lasted around 26 days. The cost of Customer Due Diligence for the intermediaries is on average around $40 million per year. This is due to the inefficiencies of the actual processes, to the increase of FTE required as result of the increasing controls defined by Regulators and to the loss incurred by the stop of customer profiling practices, which are extremely slow and complex.

Risk Management 2.0

In the last few years, the role of the Risk Management has significantly changed from a static supervision of Front Office activities to a dynamic and integrated framework involving all Bank’s divisions.

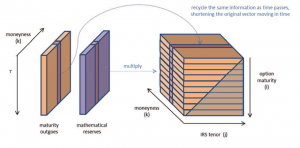

However, the evolution of Risk Management not only goes through a change in its approach but also through a substantial IT architecture revolution.

The main habit is creating a fully integrated risk ecosystem able to feed itself from many banking systems, performing checks and regular data monitoring through cognitive learning.

The change of position from an independent risk management to a completely centralized one allows obtaining advantages as:

- cost reduction ensuring a unique architecture;

- greater flexibility in its updating / evolution;

- reduction of the effort (FTE) for the intra system reconciliation;

- greater uniformity in the compliance checks;

- standardization of information sources for all disclosures maintaining consistency.

Nowadays, considering the status of the RegTech area, populated by many start-ups and differentiated solutions without a consolidate best practice, there are some barriers to its completed implementation:

- preference in financial industry for business investments rather than innovation;

- the needed investments cannot rest on previous investments in Compliance;

- continuous changes about the regulatory requirements still ongoing;

- challenges for the RegTech start-ups to interface with the IT structures, potentially not adequate for the ongoing system.

Implications for the Regulators

Financial System increasingly focuses its attention on the supervisory authorities by requiring them a costs reduction/complexity in the face of a greater quality of the controls put in place.

If on one hand, the institutions try to apply FinTech’s innovations to their own disclosure activity, on the other hand, it is advisable that the Regulators invest in similar technological innovations in order to manage a considerable amount of required data through new regulations.

The potential benefits are:

- creation of preventive compliance system developed to anticipate any breach

- performing real-time analysis and checks rather than only historical ones

- possibility to carry out more complete analysis on a wider data panel and not only on aggregations already provided without the underlying details

- implementing simple tools to increase the information level against a reduction of the overall effort (eg. fingerprint for the access to the trading platforms).

All of this also brings benefits to the entire financial system:

- defining framework at national level but especially at international level so as to reduce progressively the potential arbitrages between markets

- increasing the flexibility (both on banking institutions and Regulators) to analyze different sets of data by avoiding development costs and the related implementation time as result of these changes

- making compliance architecture an useful analysis tool to monitor impacts of new regulation through an ad-hoc scenario analysis.

Conclusions

RegTech represents one of the most important challenges of the financial system, which is able to modify structurally the global financial markets.

Despite the entry barriers to the use of technology in a regulatory environment, the banking institutions will necessarily have to evolve their way to relate with Regulators by making the process less costly and more efficient and at the same time by maintaining their competitiveness on the market.

With regard to this, the approach suggested by the literature is to acquire pilot or “sandbox” cases in order to adopt gradually an innovative process without causing potentially negative impacts.

Particularly, the institutions need this application in the trading field where the new regulations require a remarkable quantity of data and computational speed not manually sustainable.

In addition, the Supervisory Authority is willing to avoid the situation where it has the needed information for supervisory purposes but it is not able to analyze them promptly and correctly. For this purpose, the Supervisory Authority are slightly more static because they are still stuck on the old paradigm and on the review of the main regulations.

Alberto Capizzano – Director Deloitte Consulting

Silvia Manera – Manager Deloitte Consulting

Bibliography

Douglas, W. A., Janos, N. B., & Ross, P. B. (2016, October 1). FinTech, RegTech and the Reconceptualization of Financial Regulation. Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business, Forthcoming, p. 51.

Groenfeldt, T. (2018, 04 4). Understanding MiFID II’s 30,000 Pages Of Regulation Requires RegTech. Forbes, p. 1.

Imogen, G., Gray, J., & Gavin, P. (2016). FCA outlines approach to RegTech. Fintech, United Kingdom, 1.

R.T. (s.d.). KYC onboarding still a pain point for financial institutions: https://blogs.thomsonreuters.com/financial-risk/risk-management-and-compliance/kyc-onboarding-still-a-pain-point-for-financial-institutions/